The Carlisle Experiment: Unearthing the Complex Legacy of America’s First Off-Reservation Indian Boarding School

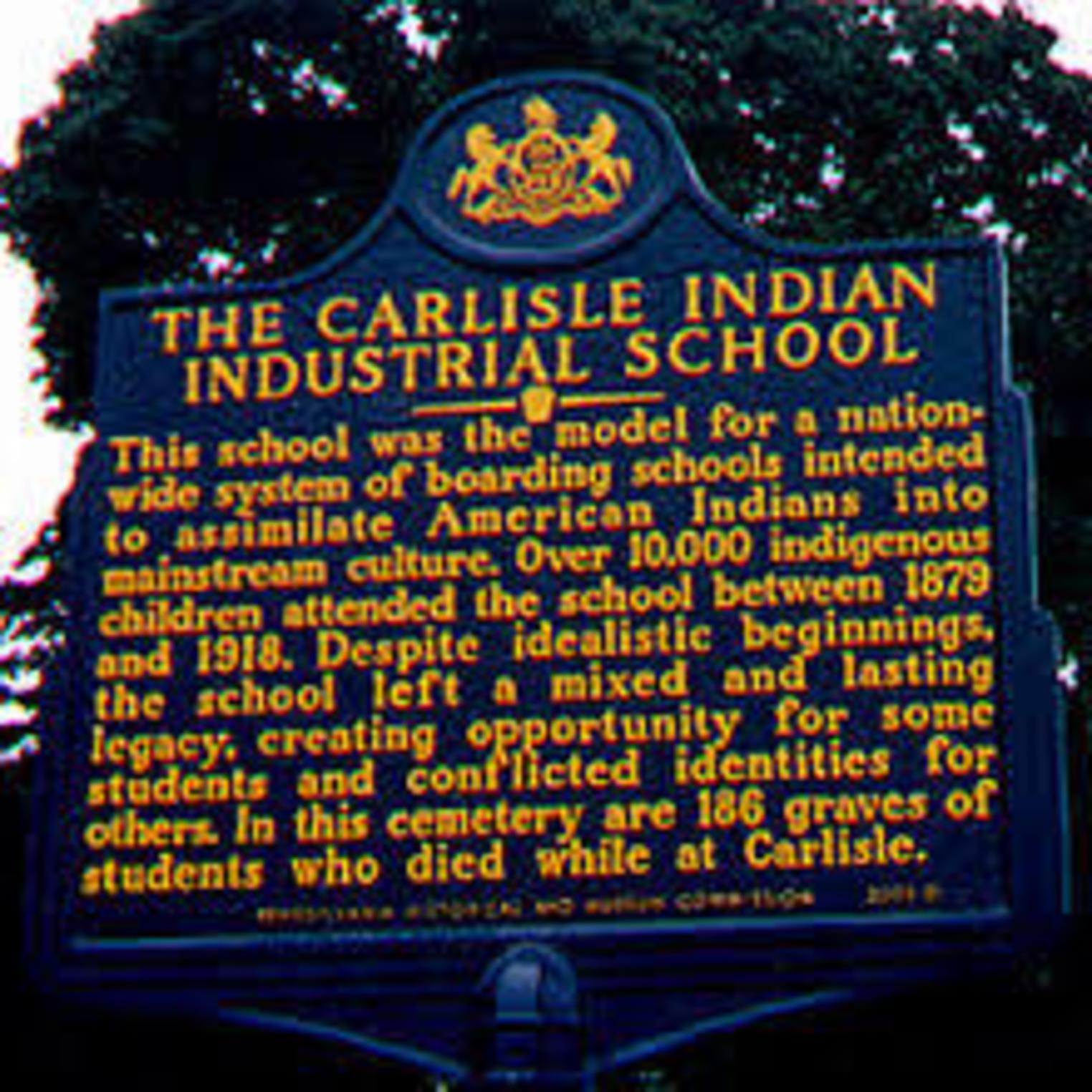

CARLISLE, PENNSYLVANIA – Nestled in the quiet, historic town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, stands a place steeped in a history both noble in its stated intent and devastating in its execution. For nearly four decades, from 1879 to 1918, the grounds that once housed a U.S. Army barracks became the site of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, America’s flagship off-reservation boarding school for Native American children. It was here that a radical social experiment unfolded, designed not just to educate, but to fundamentally transform and assimilate Indigenous youth into Anglo-American society, embodying the chilling philosophy of its founder: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man."

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was more than just a school; it was a crucible of forced cultural assimilation, a grand, tragic experiment born from the crucible of post-Civil War America and the relentless westward expansion. As the frontier closed and the last vestiges of armed conflict between the U.S. government and Native nations dwindled, a new "Indian policy" emerged. The prevailing view among many white Americans and policymakers was that the "Indian problem" could be solved not through extermination, but through "civilization."

The Architect of Assimilation: Richard Henry Pratt

At the heart of this transformative vision was Captain Richard Henry Pratt, a veteran of the Plains Wars and a staunch advocate for Native American assimilation. Pratt believed that by removing Indigenous children from the perceived "savagery" of their tribal communities and immersing them in white American culture, they could be "elevated" and integrated into the mainstream. His infamous mantra, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," was not a call for physical violence, but a chillingly literal expression of his belief that Native identities, languages, religions, and traditions had to be eradicated for Indigenous people to survive and thrive in a rapidly changing America.

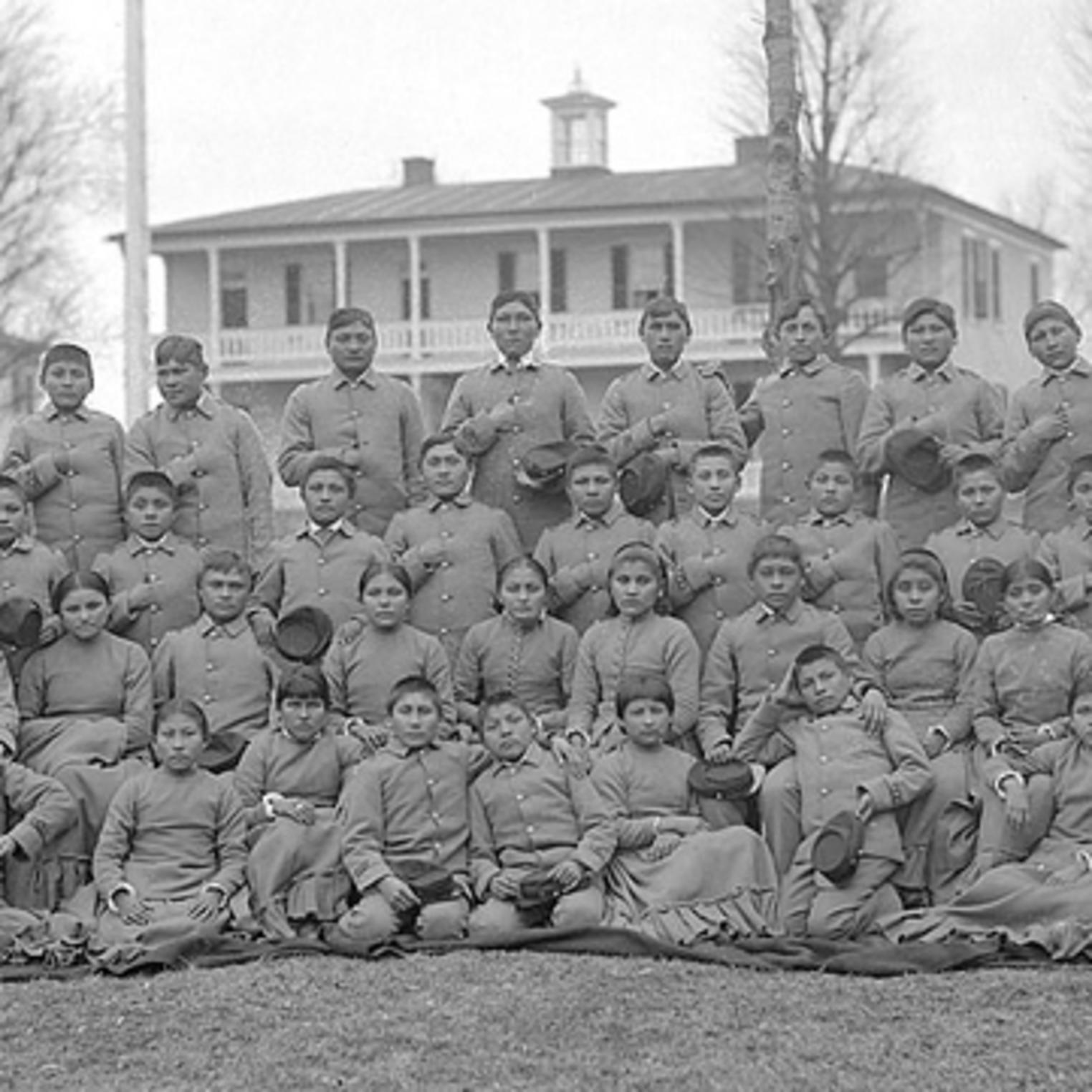

Pratt, drawing on his military background, ran Carlisle with strict discipline and an almost military-like precision. Students were often recruited, or in many cases, coerced from reservations across the country, some as young as five or six years old. Upon arrival, the transformation began immediately.

A Forced Metamorphosis: Life at Carlisle

The first act of "civilization" was often a haircut. Long hair, a symbol of identity and spiritual connection in many Native cultures, was shorn. Traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms: military-style for boys, Victorian dresses for girls. Indigenous names were replaced with English ones, often arbitrarily assigned from a list or based on a teacher’s whim. Speaking Native languages was strictly forbidden, enforced by severe punishments, including corporal punishment.

The curriculum at Carlisle was bifurcated, reflecting Pratt’s belief in vocational training over purely academic pursuits. Half the day was dedicated to classroom instruction, focusing on English, arithmetic, and American history, often taught through a lens that demonized Native cultures and celebrated white American expansion. The other half of the day was dedicated to "industrial training." Boys learned trades like carpentry, blacksmithing, farming, and printing, while girls were taught domestic skills such as cooking, sewing, laundering, and housekeeping – all designed to prepare them for roles as laborers and servants in white society.

One of Carlisle’s most distinctive features was the "Outing System." This program placed students with white families, typically farmers or townspeople, for weeks or months at a time, often during the summer. While ostensibly designed to provide practical experience and further immersion in American life, it frequently devolved into a system of cheap labor, with students exploited and sometimes abused, isolated from their peers and stripped of any remaining cultural connections.

The Human Cost: Trauma and Resilience

The impact of the Carlisle experiment on its students was profound and often devastating. Separated from their families, languages, and cultures, many experienced deep emotional and psychological trauma. The abrupt loss of identity, coupled with the harsh discipline and the constant pressure to conform, led to feelings of displacement, loneliness, and confusion. Many children suffered from homesickness so severe it manifested as physical illness.

Disease was rampant at Carlisle. Overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and the introduction of new illnesses to students with limited immunity led to frequent outbreaks of tuberculosis, influenza, and other contagious diseases. Tragically, nearly 200 children are known to have died at the school, many buried in the on-campus cemetery, far from their ancestral lands and families. For years, the graves were unmarked or poorly maintained, a poignant symbol of the school’s disregard for the individual lives it sought to erase.

Despite the relentless pressures, Native students at Carlisle exhibited remarkable resilience. While many internalized the assimilationist messages, others found subtle ways to resist. They would speak their languages in secret, share traditional stories, or practice ceremonies when they could. Some ran away, desperate to return to their homes. For others, the education received, particularly vocational skills, did offer pathways to employment and survival in a changing world, though often at an immense personal cost.

Notable Figures and the Unsettled Legacy

Among the tens of thousands of Native children who passed through Carlisle’s gates, one name stands out: Jim Thorpe. A Sac and Fox and Potawatomi athlete, Thorpe became one of the greatest all-around athletes in American history, winning Olympic gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon in 1912. His success was often held up by the school as proof of its "civilizing" mission, a testament to what Indigenous people could achieve once they shed their "savage" ways. Yet, even Thorpe’s story is complex, marred by the stripping of his Olympic medals (later posthumously restored) and the lifelong struggles many boarding school survivors faced.

As the 20th century progressed, public and governmental attitudes toward Native American policy began to shift. Reports emerged highlighting the failures and abuses of the boarding school system. The Meriam Report of 1928, though published after Carlisle’s closure, critically exposed the dire conditions, inadequate education, and detrimental psychological effects of these schools. The assimilationist policies began to wane, and in 1918, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School closed its doors, its buildings repurposed for other uses.

Today, the legacy of Carlisle, and the broader Indian boarding school system it spearheaded, continues to reverberate through Native American communities. Generations of families have been impacted by the intergenerational trauma of cultural loss, language erosion, and the psychological scars left by forced assimilation. Many survivors still grapple with the loss of their childhoods and the profound disconnection from their heritage.

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort by Native nations and descendants to reclaim the history of Carlisle. Efforts to identify and repatriate the remains of children buried in the school’s cemetery to their home communities have gained momentum, providing a measure of healing and closure for families separated by more than a century. These repatriation ceremonies are powerful acts of remembrance, acknowledging the lives lost and the cultures suppressed.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School stands as a potent symbol of a dark chapter in American history, a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of policies driven by ethnocentric beliefs and the desire to erase distinct cultures. It serves as a vital lesson that true progress lies not in forced assimilation, but in respecting and celebrating the rich diversity of all peoples. Understanding Carlisle is not just about recounting history; it is about confronting the past, acknowledging its enduring impact, and committing to a future where such injustices are never repeated.