The Enduring Enigma: A History of Native American Reservations

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

The vast, often stark landscapes of Native American reservations across the United States are more than just geographical markers; they are living testaments to a complex, often tragic, yet remarkably resilient history. From their inception as forced enclaves to their modern-day roles as centers of cultural revival and self-determination, reservations embody centuries of shifting federal policies, broken promises, and the unwavering spirit of Indigenous peoples. Understanding their history is crucial to grasping the ongoing challenges and triumphs of Native nations in America.

The Seeds of Separation: Early Encounters and the Removal Era

Before the arrival of European settlers, Indigenous nations thrived across the continent, governing themselves, managing their lands, and maintaining intricate social and economic systems. Early interactions between European powers and Native tribes often involved treaties, initially recognizing tribal sovereignty and establishing trade relations. However, as colonial ambitions grew and the concept of "manifest destiny" took hold, the narrative shifted from coexistence to conquest.

The burgeoning United States, driven by a voracious hunger for land, began to view Native nations not as sovereign entities but as obstacles to expansion. This pressure culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed into law by President Andrew Jackson. Despite a Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and condemned Georgia’s actions, Jackson famously defied the decision, stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it."

This act legalized the forced relocation of southeastern tribes – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – from their ancestral lands to designated territories west of the Mississippi River, primarily in what is now Oklahoma. The infamous Trail of Tears in the late 1830s saw thousands of Cherokee, ill-equipped and suffering from disease and starvation, die during their forced march. It was a brutal precursor to the reservation system, establishing the precedent of isolating Indigenous populations to facilitate white settlement.

The Reservation System Takes Shape: Confinement and Control

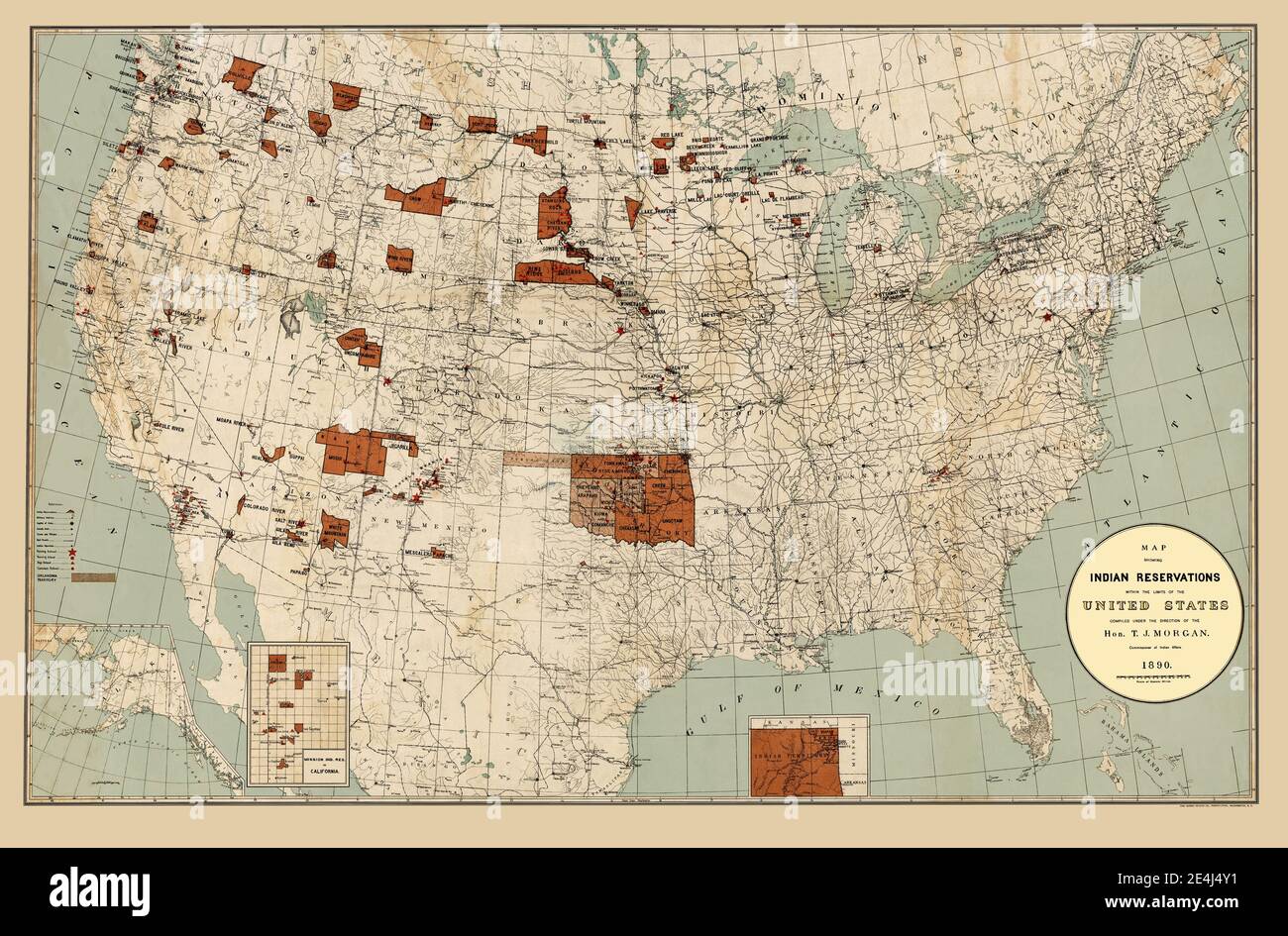

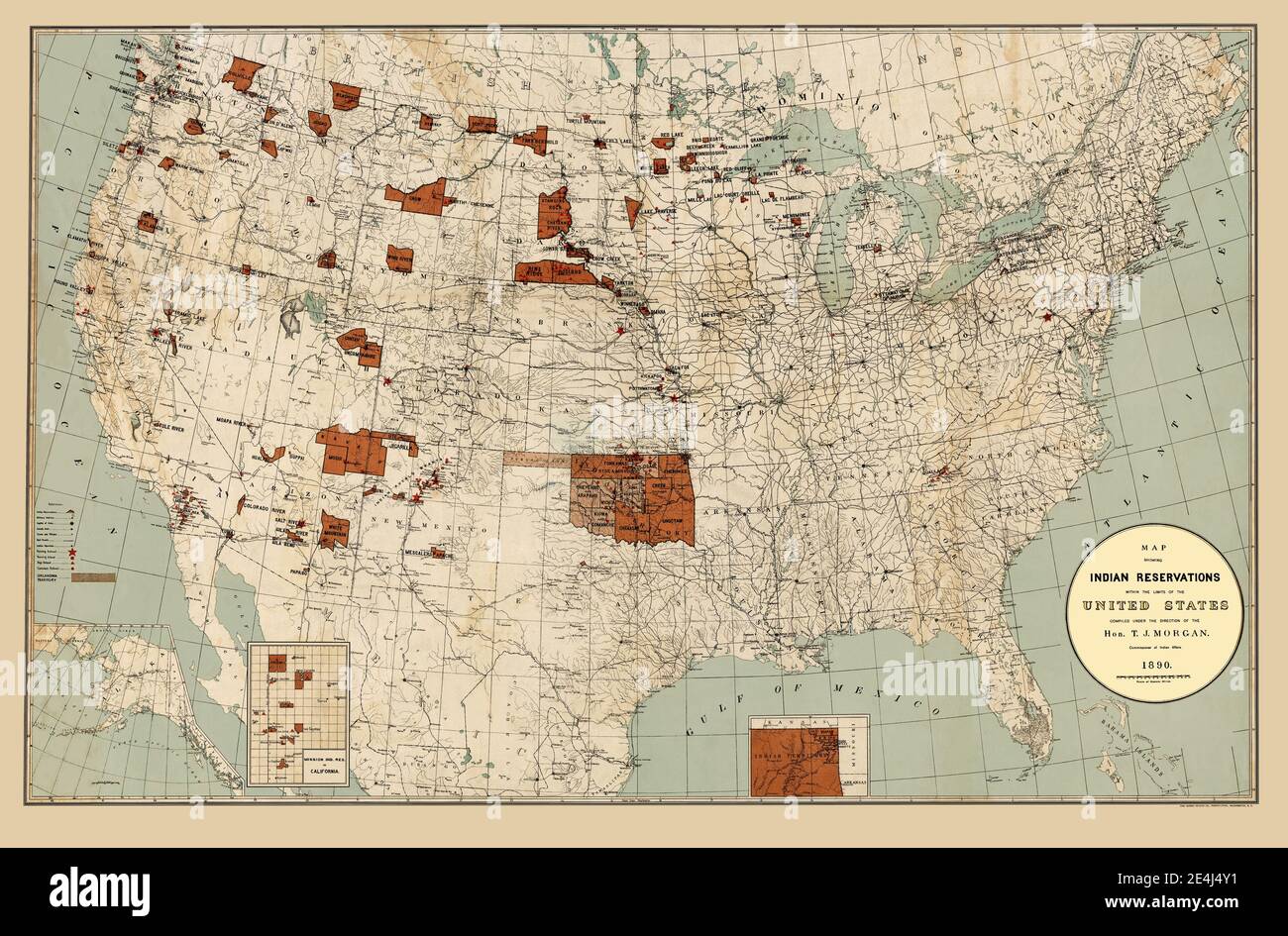

By the mid-19th century, as the frontier diminished and armed conflicts between tribes and the U.S. military intensified, the policy of outright removal evolved into one of confinement. The idea was to concentrate Native peoples onto defined, often remote, tracts of land, thereby "pacifying" them and opening up the vast majority of their former territories for non-Native settlement and resource extraction.

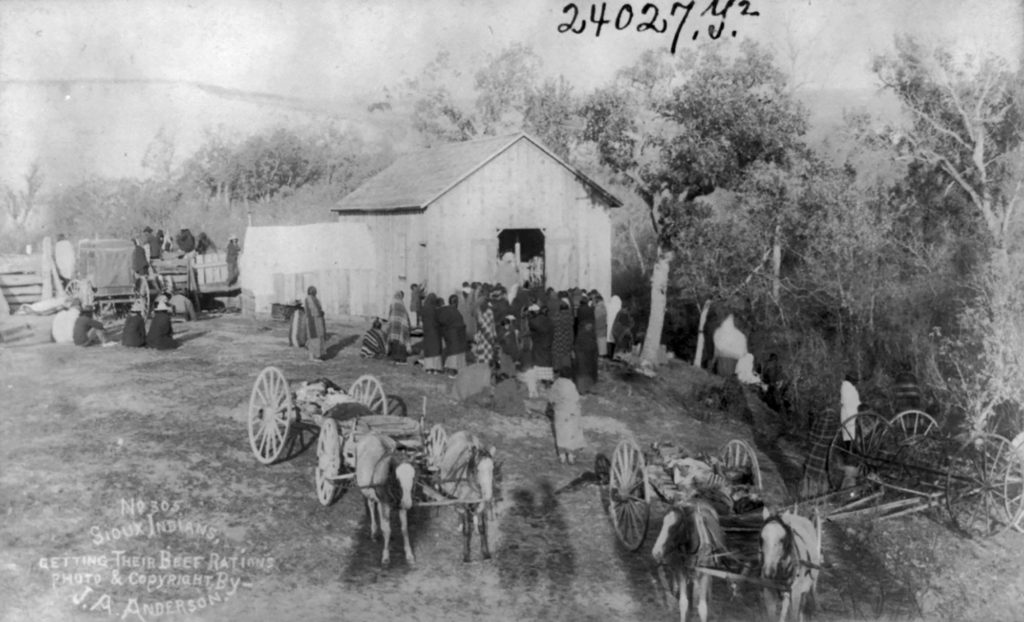

These early reservations were often desolate, infertile lands, far removed from tribal sacred sites and traditional hunting grounds. The treaties that established them were frequently signed under duress, misinterpreted, or outright violated by the U.S. government. Native Americans were stripped of their self-sufficiency and made dependent on federal rations, tools, and supplies, which were often insufficient or of poor quality.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), initially part of the War Department and later transferred to the Department of the Interior, became the primary federal agency responsible for managing reservation life. Its role was often paternalistic and controlling, regulating nearly every aspect of tribal existence, from land use and governance to education and economic activity. Agents often enforced assimilationist policies, suppressing Native languages, spiritual practices, and traditional forms of governance. This period laid the groundwork for decades of poverty, disempowerment, and cultural erosion on reservations.

The Allotment Era: Breaking Up Communal Lands and Culture

The late 19th century saw a new, insidious policy emerge, driven by the belief that private land ownership was the key to "civilizing" Native Americans and integrating them into mainstream American society. The Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Act) was designed to dismantle communal tribal land holdings.

Under the Dawes Act, reservation lands were surveyed and divided into individual plots, typically 160 acres, to be allotted to individual Native American families. The "surplus" lands – often millions of acres – remaining after allotments were made were then declared open for sale to non-Native settlers. The stated goal was to encourage farming and individual enterprise, but the actual outcome was devastating.

As Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, famously articulated the prevailing philosophy: "Kill the Indian, save the man." This ethos permeated the allotment policy, which sought to break the bonds of tribal identity and communal living. The results were catastrophic: Native Americans lost an estimated two-thirds of their land base – from approximately 150 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million acres by 1934. The checkerboard pattern of land ownership created by allotment also complicated tribal governance and economic development for generations. Many allottees, unfamiliar with Anglo-American property laws or unable to pay taxes, lost their land to foreclosures or fraudulent sales.

The Indian New Deal: A Brief Respite and Self-Governance

The disastrous consequences of the Dawes Act became undeniable by the 1930s. The Great Depression, coupled with widespread poverty and social disarray on reservations, prompted a significant shift in federal policy. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, championed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, marked a turning point.

Often referred to as the "Indian New Deal," the IRA aimed to reverse the assimilationist policies of the past. It ended the allotment policy, restored some tribal lands, and encouraged tribes to adopt their own constitutional governments, often based on Western models. The IRA also sought to promote Native American economic development and cultural preservation.

While not universally embraced by all tribes (some viewed it as another form of federal imposition), the IRA represented the first major legislative effort to recognize and support tribal sovereignty and self-governance in decades. It laid the groundwork for future advancements in Native rights, but its impact was limited by the subsequent policy shifts.

Termination and Relocation: A Return to Assimilationist Pressures

The post-World War II era saw another dramatic and harmful reversal in federal policy. Influenced by Cold War anxieties and a desire to reduce federal spending, Congress adopted a policy of "termination" in the 1950s. The goal was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society by ending their unique relationship with the federal government, liquidating tribal assets, and dissolving tribal governments.

House Concurrent Resolution 108 (1953) declared it to be the sense of Congress that Native Americans should be freed from federal supervision "as rapidly as possible." Public Law 280 (1953) transferred federal jurisdiction over criminal and civil matters on certain reservations to state governments, often without tribal consent or adequate resources for states to manage the new responsibilities.

Over 100 tribes, bands, and communities were terminated between 1953 and 1964, including the Menominee of Wisconsin and the Klamath of Oregon. These tribes lost their federal recognition, their lands, and their access to federal services, leading to devastating economic hardship, cultural disruption, and increased poverty.

Simultaneously, the federal government promoted "relocation" programs, encouraging Native Americans to move from reservations to urban centers with promises of jobs and housing. While some found opportunities, many encountered discrimination, unemployment, and a profound sense of cultural isolation in cities, far from their traditional communities and support systems.

The Era of Self-Determination: Reclaiming Sovereignty

The failures of termination and relocation became painfully clear by the late 1960s and early 1970s. Inspired by the broader Civil Rights Movement and fueled by growing Native American activism (epitomized by groups like the American Indian Movement, AIM, and events like the occupation of Alcatraz and Wounded Knee), a new policy of "self-determination" began to emerge.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon formally repudiated the termination policy, stating, "The first Americans—the Indians—are the most deprived and most isolated minority group in our nation." This shift culminated in the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This landmark legislation empowered tribes to contract with the BIA and other federal agencies to administer their own programs and services, including education, healthcare, and law enforcement.

The Self-Determination era has allowed tribes to regain significant control over their own affairs, fostering a renaissance of cultural pride, language revitalization, and economic development. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, for instance, has enabled many tribes to establish casino operations, generating revenue that supports essential services, infrastructure, and cultural programs on reservations.

The Enduring Legacy and Future Prospects

Today, Native American reservations continue to face formidable challenges, including high rates of poverty, unemployment, inadequate healthcare, and educational disparities. The historical trauma inflicted by centuries of colonial policies, forced removals, land loss, and cultural suppression continues to reverberate through generations. Jurisdictional complexities between tribal, state, and federal governments also present ongoing hurdles.

However, reservations are also vibrant centers of Indigenous life, resilience, and innovation. They are places where Native languages are being revitalized, traditional ceremonies are practiced, and sovereign nations are asserting their rights to govern their own people and manage their own resources. From renewable energy projects and sustainable agriculture to tourism and advanced manufacturing, tribes are diversifying their economies and building stronger, more self-sufficient communities.

The history of Native American reservations is a testament to the enduring power of Indigenous identity and the relentless pursuit of sovereignty. It is a narrative woven with threads of betrayal and hardship, but also with remarkable strength, adaptation, and an unwavering determination to preserve cultures, languages, and ways of life that have survived against tremendous odds. As Native nations continue to chart their own futures, the reservations stand as powerful symbols of both past injustices and a future built on self-determination and cultural renewal.