Echoes of Resilience: A History of Native American Resistance

The narrative of American history is often painted with broad strokes of expansion and progress, a westward march fueled by destiny. Yet, beneath this dominant tale lies a parallel, enduring saga: the unwavering, multifaceted resistance of Native American peoples. For over 500 years, from the first European landings to the present day, Indigenous nations have fought – with arms, diplomacy, culture, law, and spirit – to preserve their lands, sovereignty, and way of life. This is not a story of singular battles, but a continuous, evolving struggle for survival against overwhelming odds, a testament to an unyielding spirit.

The First Encounters: A Clash of Worlds and the Seeds of Defiance

When European ships first touched the shores of the Americas, they encountered not a wilderness, but a continent teeming with diverse, complex civilizations. Initial interactions often involved curiosity and trade, but quickly devolved into conflict as European colonizers sought land, resources, and dominion. Disease, intentionally or unintentionally introduced, decimated Native populations, weakening their ability to resist. Yet, even in the face of biological catastrophe, resistance took root.

One of the earliest and most remarkable instances of successful, unified resistance occurred in 1680: the Pueblo Revolt in what is now New Mexico. Led by Popé, a Tewa religious leader, the Pueblo people, who had suffered decades of brutal Spanish rule, forced conversions, and exploitation, rose up. In a meticulously planned and executed uprising, they killed hundreds of Spanish settlers and drove the remainder out of the territory, maintaining their independence for twelve years. This rebellion stands as a powerful early example of a coordinated, inter-tribal effort to reclaim sovereignty and culture.

Further east, as English colonies expanded, tensions escalated. The Pequot War (1637) in New England, a brutal conflict ending in the near annihilation of the Pequot tribe, served as a chilling precursor. Yet, it also solidified a fierce determination among other tribes. King Philip’s War (1675-1678), led by Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), the Wampanoag sachem, saw a pan-tribal confederacy launch a devastating war against the New England colonies. Though ultimately defeated, with immense casualties on both sides, it was one of the bloodiest conflicts in American colonial history, demonstrating the capacity for Native nations to unite and inflict severe damage on colonial powers. As historian Jill Lepore noted, it was "the last great stand of New England Indians against English expansion."

The Crucible of Empires: Alliances, Deception, and Shifting Borders

As European empires vied for control of the continent, Native nations were often caught in the crossfire, or strategically allied themselves to advance their own interests. The French and Indian War (1754-1763), part of the global Seven Years’ War, saw tribes like the Huron and Algonquin largely side with the French, while the powerful Iroquois Confederacy played a complex game of neutrality and alliance with the British. These alliances were not born of blind loyalty, but calculated attempts to leverage European rivalries to protect their lands and maintain their power balance. When the British emerged victorious, Native allies of the French found themselves in a precarious position, leading to further resistance.

Pontiac’s War (1763-1766), led by the Ottawa chief Pontiac, erupted in the Great Lakes region as Native groups resisted British post-war policies and encroachment. Pontiac’s vision was to drive the British out and restore a traditional way of life, symbolizing a broader pan-tribal resistance against a common oppressor. Though the uprising eventually faded, it forced the British to issue the Proclamation of 1763, which, in theory, limited colonial expansion west of the Appalachian Mountains, a temporary victory for Native sovereignty.

The American Republic and the Onslaught of Manifest Destiny

The birth of the United States brought a new, more relentless pressure on Native lands. The young republic, fueled by ambitions of westward expansion and a concept of "Manifest Destiny," systematically pursued policies of removal and assimilation. This era witnessed some of the most iconic figures and tragic events of Native resistance.

Tecumseh, a Shawnee chief, emerged as a visionary leader in the early 19th century. He tirelessly worked to forge a pan-tribal confederacy stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, advocating that land was held communally by all Native peoples and could not be sold by individual tribes. "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth?" he famously declared. His efforts, alongside his brother Tenskwatawa (the Prophet), led to the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811) and later, Tecumseh’s alliance with the British in the War of 1812. His death in the Battle of the Thames (1813) dealt a severe blow to his dream of a unified Indigenous resistance, but his legacy of inter-tribal solidarity endured.

The Seminole Wars (1816-1858) in Florida represent one of the longest and costliest conflicts in American history. The Seminoles, a diverse group of Creek, other Native peoples, and escaped African slaves, fiercely resisted forced removal from their homelands. Led by figures like Osceola, they employed guerrilla warfare tactics, utilizing Florida’s dense swamps to their advantage, inflicting heavy casualties on U.S. forces. Despite their eventual defeat and forced removal to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), their protracted resistance underscored the immense human and financial cost of conquest.

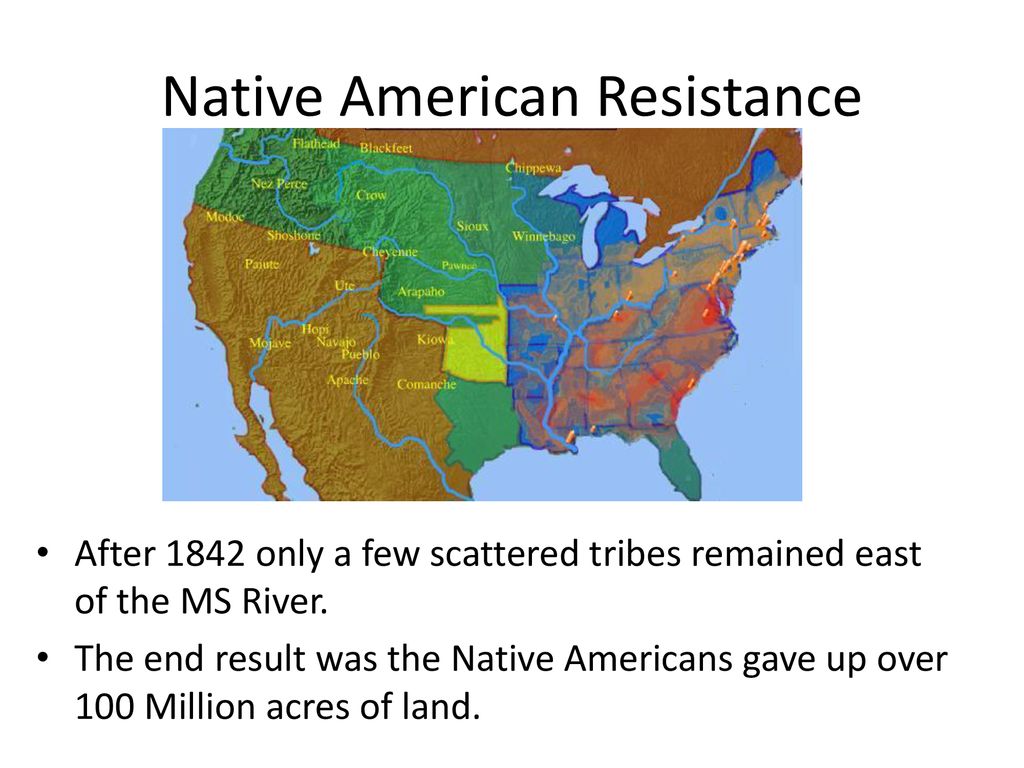

The infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830 epitomized the U.S. government’s policy. While many tribes were forcibly removed, resulting in the "Trail of Tears" – a horrific forced march that claimed thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole lives – resistance also took legal forms. The Cherokee Nation famously challenged Georgia’s land claims in the Supreme Court, winning in Worcester v. Georgia (1832). However, President Andrew Jackson defiantly ignored the ruling, famously stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This episode tragically highlighted the limits of legal resistance against a determined, expansionist government.

The Plains Wars: The Last Stand of Armed Resistance

As the 19th century progressed, the focus of conflict shifted westward to the Great Plains. The discovery of gold, the construction of railroads, and the relentless flow of settlers brought the U.S. Army into direct, often brutal, confrontation with the powerful nomadic tribes of the Plains: the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Apache, whose lives revolved around the buffalo.

Massacres like Sand Creek (1864), where U.S. volunteers brutally murdered over 150 unarmed Cheyenne and Arapaho, mostly women and children, fueled a cycle of retaliation and war. The Fetterman Fight (1866), where a combined force of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho ambushed and annihilated a U.S. Army detachment, was a significant Native victory.

The most famous engagement of the Plains Wars was the Battle of Little Bighorn (1876), often called "Custer’s Last Stand." Under the leadership of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors decisively defeated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry, killing Custer and over 260 of his men. This stunning victory, however, only intensified the U.S. government’s resolve to subdue the Plains tribes.

The subsequent years saw the relentless hunting of the buffalo to near extinction – a deliberate strategy to destroy the Plains tribes’ primary food source and way of life – and a series of campaigns that slowly broke Native resistance. Leaders like Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce (1877), after a 1,170-mile strategic retreat, famously surrendered with the poignant words: "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever." In the Southwest, Geronimo and his small band of Apache warriors waged a tenacious guerrilla war for decades, evading thousands of U.S. and Mexican soldiers until his final surrender in 1886.

The era of armed resistance effectively ended with the Wounded Knee Massacre (1890) in South Dakota. U.S. troops surrounded a band of Lakota, primarily women, children, and elders, and massacred nearly 300 of them. This horrific event, largely seen as a deliberate act of retribution and a final crushing blow to the Ghost Dance movement (a spiritual revival that sought to restore Native ways and repel white encroachment), symbolized the tragic end of large-scale armed Native American resistance.

Beyond the Battlefield: Resisting Assimilation in the 20th Century and Beyond

The turn of the 20th century marked a new phase of resistance. With military defeat, Native peoples faced the devastating policies of forced assimilation: the infamous boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian, save the man," the Dawes Act which broke up communal lands, and the suppression of traditional cultures and languages. Yet, resistance persisted, shifting from armed conflict to legal, political, and cultural fronts.

The mid-20th century saw the rise of Native American civil rights movements. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, brought a militant, direct-action approach to advocating for treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, and the redress of historical injustices. Their actions, such as the occupation of Alcatraz Island (1969-1971) by "Indians of All Tribes" and the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties march on Washington D.C., which culminated in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, brought national and international attention to Native American grievances. The 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation, a 71-day standoff between AIM activists and federal agents, was a symbolic reclamation of a site of historical trauma and a powerful demand for justice.

The passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 was a landmark achievement, allowing tribes greater control over their own affairs and resources, a direct result of decades of advocacy and pressure. Legal battles over treaty rights, land claims, and environmental protection became central to modern resistance, with tribes often leveraging their sovereign status to protect their interests.

In the 21st century, Native American resistance continues to evolve. The fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock (2016-2017) became a global symbol of Indigenous environmental activism and the protection of sacred lands and water. Led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the movement brought together thousands of Indigenous people and allies, highlighting the ongoing struggle against resource extraction projects that threaten tribal sovereignty and the environment. Similarly, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement has brought critical attention to the disproportionately high rates of violence against Native women and girls, advocating for justice and systemic change.

A Legacy of Unbroken Spirit

The history of Native American resistance is not a linear progression from armed conflict to peaceful protest, but a dynamic, interwoven tapestry of defiance. It is a story of profound loss and unimaginable suffering, but also of incredible resilience, adaptation, and an enduring commitment to cultural identity and self-determination. From the strategic brilliance of Popé and Tecumseh to the fierce determination of Osceola and Crazy Horse, and from the political savvy of legal advocates to the spiritual power of water protectors at Standing Rock, Native peoples have consistently asserted their right to exist, to govern themselves, and to honor their ancestral ways.

This history serves as a powerful reminder that "America" was not an empty wilderness to be settled, but a vibrant continent fiercely defended by its original inhabitants. The echoes of their resistance continue to reverberate, shaping ongoing struggles for justice, sovereignty, and a future where Indigenous voices are heard, respected, and empowered. It is a testament to the fact that even in the face of centuries of oppression, the spirit of Native American resistance remains unbroken.