The Silent Conqueror: How Disease Decimated Native America

When Christopher Columbus’s ships first touched the shores of the Americas in 1492, they carried more than just eager explorers, ambitious conquistadors, and dreams of gold. Unbeknownst to them, they also transported an invisible, far more potent force: a microbial arsenal that would unleash an unparalleled demographic catastrophe upon the Indigenous peoples of the New World. While popular narratives often emphasize the brutality of warfare and the greed of land seizures, it was the silent, relentless march of Old World diseases, against which Native Americans had no immunity, that became the primary architect of their decimation, irrevocably altering the course of history and laying the groundwork for European dominance.

Before European contact, the Americas were far from a pristine wilderness sparsely populated by nomadic tribes. Instead, they were home to vibrant, complex, and highly diverse societies. From the sophisticated urban centers of the Aztec and Inca empires, boasting populations in the millions, to the vast agricultural networks of the Mississippi Valley, and the intricate societal structures of the Northeastern woodlands, Indigenous civilizations had flourished for millennia. They had developed advanced agricultural techniques, intricate spiritual beliefs, complex political systems, and extensive trade networks spanning continents. However, their long isolation from Afro-Eurasian populations meant they had also developed a unique immunological profile, one tragically vulnerable to a host of pathogens that had become endemic in the Old World.

This vulnerability led to what historians and epidemiologists refer to as "virgin soil epidemics." Unlike populations in Europe, Asia, and Africa who had lived for centuries with diseases like smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus, developing some degree of inherited or acquired immunity, Native Americans had none. When these diseases arrived, often preceding the actual physical presence of Europeans, they ripped through communities with unprecedented ferocity. The consequences were not merely high death tolls but societal collapse on a scale unimaginable in modern times.

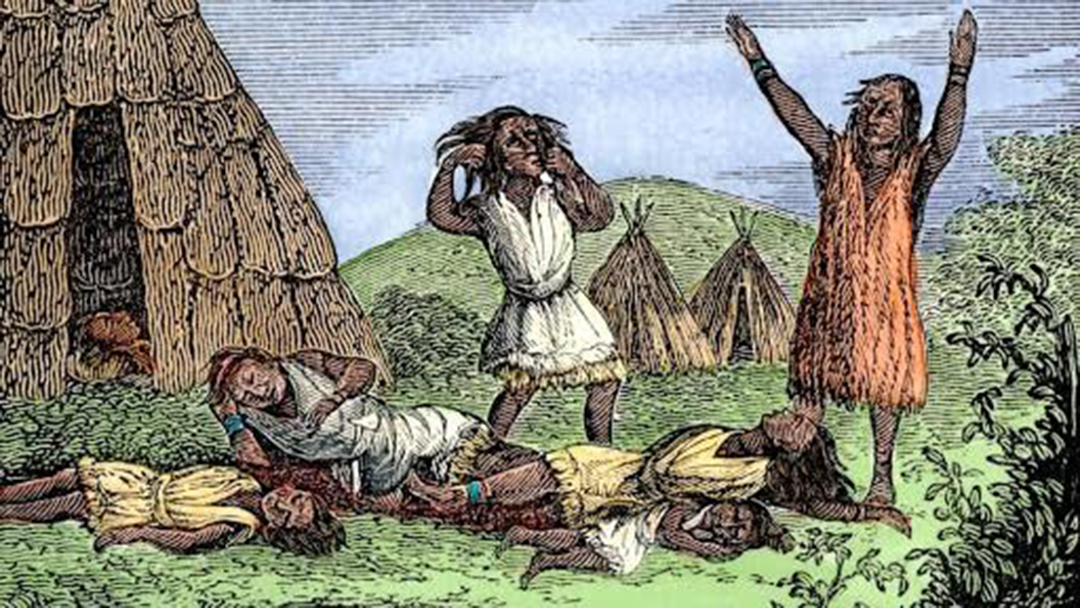

Smallpox was arguably the most devastating of these microbial invaders. A highly contagious disease with a brutal fatality rate, especially among those without prior exposure, smallpox would often sweep through entire villages, leaving behind a horrifying landscape of death and desolation. Its symptoms – high fever, excruciating headaches, and a distinctive rash that turned into pus-filled blisters covering the body – were terrifying. Survivors were often left blind, disfigured, or sterile.

The impact of smallpox on the great Mesoamerican empires serves as a chilling testament to its power. When Hernán Cortés marched on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1520, a smallpox epidemic was already raging through the city, having been introduced by an infected member of a Spanish expedition. The disease claimed the life of Cuitláhuac, the Aztec emperor who had successfully repelled Cortés, just 80 days into his reign. This loss of leadership, coupled with the mass incapacitation and death of warriors and civilians, crippled the city’s defenses and demoralized its inhabitants. The Spanish, who often suffered only mild cases or were immune, found themselves fighting a population already ravaged and weakened by disease. The once-thriving Tenochtitlan, a city of hundreds of thousands, saw its population plummet by estimates of 50-90% within a few years.

Similarly, in the Inca Empire, smallpox arrived even before Francisco Pizarro and his conquistadors. It swept through the Andes in the 1520s, triggering a devastating civil war for succession. The reigning Inca emperor, Huayna Capac, and his chosen heir both succumbed to the disease. The ensuing power struggle between his sons, Atahualpa and Huáscar, left the empire divided and vulnerable, making Pizarro’s subsequent conquest astonishingly swift and relatively easy. The disease, not Spanish steel, had already laid the empire low.

Beyond smallpox, a grim procession of other Old World diseases followed, each contributing to the demographic catastrophe: measles, influenza, bubonic plague, typhus, diphtheria, cholera, mumps, and whooping cough. Each wave of disease, even if less lethal than smallpox, would further weaken a population already struggling to recover from the previous one, preventing any chance of demographic rebound. The cumulative effect was staggering. Historian Henry F. Dobyns, a pioneer in quantifying the demographic collapse, estimated that the Indigenous population of the Americas may have fallen by as much as 90% or more within the first 100-150 years of contact. From an estimated population of perhaps 50-100 million in 1492, the numbers plummeted to perhaps 5-10 million by the mid-17th century. This was, in essence, the greatest demographic disaster in human history.

The impact of disease extended far beyond mere numbers. It triggered a profound societal disintegration. The sudden loss of elders, who served as repositories of tribal history, spiritual knowledge, and practical skills, created an irreplaceable void. Shamans and healers, unable to cure the new, terrifying ailments, saw their authority and spiritual power questioned, leading to a crisis of faith and identity. Social structures, based on kinship and communal effort, fractured under the strain of mass death and the psychological terror of an invisible enemy. With so many dead, fields lay fallow, hunting expeditions were abandoned, and trade networks collapsed, leading to widespread famine and further weakening the survivors.

The psychological toll was immense. Imagine witnessing your entire family, your friends, your entire community, waste away and die, knowing that whatever traditional remedies or spiritual practices you employed were utterly useless. This created a deep-seated trauma that was passed down through generations, contributing to feelings of despair, fatalism, and a sense of having been abandoned by their gods.

This catastrophic depopulation also profoundly reshaped the political landscape. Tribes that had once been powerful were reduced to mere remnants, their military strength and political cohesion shattered. This weakened state left them highly vulnerable to European expansion. As lands became depopulated, they appeared "empty" to the arriving Europeans, fueling the concept of terra nullius (nobody’s land) and justifying further encroachment. The vast stretches of seemingly vacant land, cleared by disease, facilitated European settlement and agricultural expansion, inadvertently turning the continent into a vast, fertile ground for colonization.

The impact was not uniform across all tribes or regions. Some groups, living in more isolated areas or those who adopted early and effective quarantine measures, might have suffered less initially. However, as the frontier expanded and contact became more frequent, few groups ultimately escaped the onslaught. The Cherokee, for instance, were repeatedly hit by epidemics throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, further weakening them before the infamous Trail of Tears. Plains tribes, despite their nomadic lifestyle, were not immune; smallpox and cholera epidemics swept through their communities in the 19th century, decimating populations and contributing to the eventual subjugation of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and other nations.

Even after the initial waves of "virgin soil" epidemics, Native Americans continued to suffer disproportionately from diseases that Europeans had learned to manage. Tuberculosis, influenza, and even common colds could be far more lethal to Indigenous populations, exacerbated by poverty, malnutrition, forced relocation onto reservations, and inadequate access to healthcare. The conditions on many reservations – overcrowding, poor sanitation, and limited resources – created ideal breeding grounds for disease, perpetuating a cycle of illness and death.

In conclusion, the impact of disease on Native Americans was not merely an unfortunate historical footnote; it was the single most devastating factor in the European colonization of the Americas. It paved the way for conquest by decimating populations, shattering social structures, undermining spiritual beliefs, and creating a demographic vacuum that Europeans eagerly filled. The legacy of this biological catastrophe echoes into the present day, contributing to the health disparities, intergenerational trauma, and ongoing struggles faced by many Indigenous communities. Understanding this profound and tragic chapter of history is crucial, not only for recognizing the immense suffering endured by Native peoples but also for appreciating the resilience of those who survived and continue to preserve their cultures and identities against overwhelming odds. It serves as a stark reminder that history is not just about battles and treaties, but also about the unseen forces that can reshape continents and destinies.