The Indian Reorganization Act: A Watershed Moment in Federal Indian Policy

By the early 20th century, the landscape for Native American tribes was one of profound despair and systemic erosion. Decades of federal policies, most notably the 1887 Dawes Act (General Allotment Act), had systematically stripped Indigenous peoples of their communal lands, dismantled traditional governance structures, and aggressively pursued a policy of forced assimilation. What remained was a mosaic of fragmented reservations, deep poverty, widespread disease, and a cultural heritage under relentless assault. It was against this backdrop of crisis that the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 emerged, a legislative beacon of the New Deal era that promised a radical departure from the past. Heralded by some as the "Indian New Deal," the IRA aimed to reverse generations of destructive policies, promote tribal self-governance, and foster economic and cultural revitalization. Yet, like many sweeping reforms, its implementation was complex, its legacy profoundly mixed, and its impact still debated today.

To understand the IRA, one must first grasp the depth of the devastation it sought to address. The Dawes Act, ostensibly designed to integrate Native Americans into mainstream society by breaking up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, had been catastrophic. Between 1887 and 1934, Native landholdings plummeted from approximately 138 million acres to a mere 48 million, much of which was arid or unsuitable for farming. "Surplus" land, after allotments were made, was sold off to non-Native settlers, further fragmenting tribal territories and economic bases. This policy not only dispossessed tribes of their land but also attacked the very foundation of their communal identity and traditional ways of life. By the 1930s, Native Americans were among the poorest Americans, with high rates of unemployment, malnutrition, and disease. Their cultural practices were often suppressed, their languages discouraged, and their children forcibly sent to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian to save the man."

The architect of the IRA was John Collier, a social reformer and advocate for Native rights who had spent years documenting the dire conditions on reservations. Appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, Collier was a fervent critic of the Dawes Act and a passionate believer in the inherent value of Indigenous cultures. He envisioned a future where tribes could govern themselves, manage their own resources, and revive their traditional practices. His philosophy was rooted in the idea of cultural pluralism, a stark contrast to the assimilationist policies that preceded him. He saw the New Deal’s emphasis on relief, recovery, and reform as an opportunity to extend these principles to Native communities, arguing that the federal government had a moral obligation to rectify past injustices.

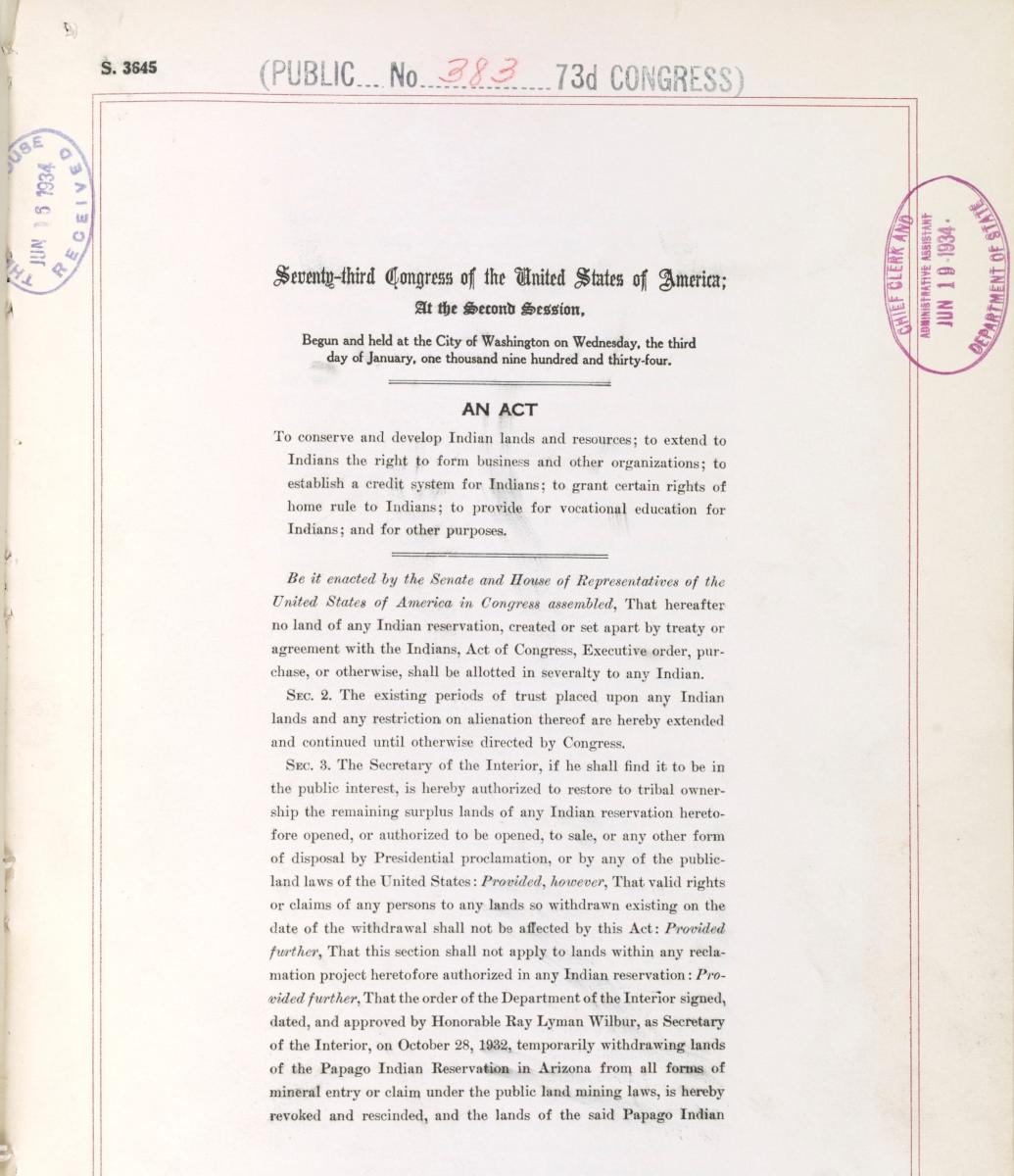

The Indian Reorganization Act, officially signed into law on June 18, 1934, was the legislative embodiment of Collier’s vision. Its core provisions were groundbreaking, aiming to fundamentally alter the relationship between the federal government and Native American tribes:

-

Ending Allotment and Restoring Land: The Act immediately halted the further allotment of tribal lands and prohibited the sale of "surplus" lands. Crucially, it established a mechanism for tribes to reacquire lost land, either through purchase by the federal government and designation as trust land, or through direct tribal purchase. This was a monumental shift, acknowledging the importance of a communal land base for tribal survival and sovereignty. While the process of land recovery was slow and often underfunded, it marked the first time in decades that the tide of land loss began to turn.

-

Promoting Tribal Self-Governance: Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of the IRA was its emphasis on tribal self-determination. It encouraged tribes to draft and adopt written constitutions and bylaws, modeled on Western democratic principles, and to elect tribal councils. These new governing bodies were empowered to manage their internal affairs, administer justice, and negotiate directly with the federal government. For tribes that adopted these constitutions, the Act also provided for federal recognition of their tribal governments, laying the groundwork for the modern concept of tribal sovereignty. Section 16 of the Act outlined the process for drafting these constitutions, and Section 17 allowed for the formation of federally chartered corporations to conduct business and manage tribal enterprises.

-

Fostering Economic Development: To support the newly empowered tribal governments and stimulate reservation economies, the IRA established a revolving loan fund. This fund provided credit for tribal enterprises, agricultural development, and educational pursuits, aiming to break the cycle of poverty and dependence. While the funds were often insufficient to meet the vast needs of the tribes, they represented a significant step towards economic self-sufficiency.

-

Preserving and Revitalizing Culture: Although not explicitly detailed in every section, the spirit of the IRA strongly supported cultural preservation. By ending forced assimilation, promoting self-governance, and encouraging tribal distinctiveness, the Act created an environment where Indigenous languages, ceremonies, and artistic traditions could be revived and celebrated without fear of federal reprisal. Collier believed that a healthy cultural identity was essential for tribal well-being and resilience.

The passage of the IRA was not without controversy, even among Native Americans themselves. Collier, despite his good intentions, was an outsider, and his reform efforts were perceived by some as another form of federal imposition, albeit a more benign one. The Act required tribes to vote on whether to accept its provisions, and the results were mixed. While 181 tribes voted to accept the IRA, 77 rejected it. The Navajo Nation, one of the largest tribes, famously rejected the Act, primarily due to concerns over proposed livestock reduction programs (which were seen as a threat to their economic base and cultural practices) and a deep-seated distrust of federal intervention. Other tribes, particularly those with strong traditional governance systems, found the imposition of Western-style constitutions and elections disruptive to their existing political structures, which often relied on consensus-building and hereditary leadership rather than majority rule.

This tension highlights one of the IRA’s most significant criticisms: its inherent paternalism. While aiming for self-determination, the Act still dictated the form that tribal self-governance should take. The prescribed constitutions often mirrored federal structures, and tribal decisions remained subject to the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, meaning the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) retained considerable oversight and control. This "top-down" approach, even with benevolent intent, often created internal divisions within tribes, empowering those who adapted to the new system while marginalizing traditional leaders.

Despite these criticisms, the IRA’s positive impacts are undeniable. It provided the legal framework for the establishment of modern tribal governments, which became crucial platforms for advocating for Native rights and asserting sovereignty in the decades that followed. It slowed, and in some cases reversed, the devastating loss of tribal land. It fostered a nascent economic development on reservations and, most importantly, created an environment where Indigenous cultures, languages, and identities could begin to heal and flourish after generations of suppression. The Act laid the groundwork for future self-determination policies, culminating in the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which allowed tribes to contract directly with the federal government to administer programs previously run by the BIA.

However, the IRA’s legacy is also intertwined with the dark shadow of the "Termination Era" of the 1950s and 1960s. Although Collier vehemently opposed such policies, the IRA’s emphasis on integrating tribes into a federal framework, combined with the perceived "success" of some tribes in managing their own affairs, ironically led some policymakers to believe that tribes were now ready to be "freed" from federal oversight. This resulted in the termination of federal recognition and services for over 100 tribes, leading to another period of immense hardship and land loss, a stark reminder that even well-intentioned policy can have unforeseen and devastating consequences.

In conclusion, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 stands as a complex and pivotal moment in American history and federal Indian policy. It was a radical, albeit imperfect, attempt to correct the historical injustices inflicted upon Native American tribes. It marked a profound shift from the destructive assimilationist policies of the past to a new emphasis on self-governance, economic development, and cultural preservation. While it introduced a new form of paternalism and created internal challenges for many tribes, the IRA provided the foundational legal and political structures upon which modern tribal sovereignty and self-determination efforts have been built. Its legacy is a testament to the enduring resilience of Native American peoples and a constant reminder of the ongoing journey towards true self-governance, free from the dictates of external powers. The IRA was not a panacea, but it was undoubtedly a watershed, shifting the course of federal-tribal relations and laying essential groundwork for the vibrant, self-governing Native nations of today.