The Long Walk: A Nation’s Forced Odyssey and Enduring Spirit

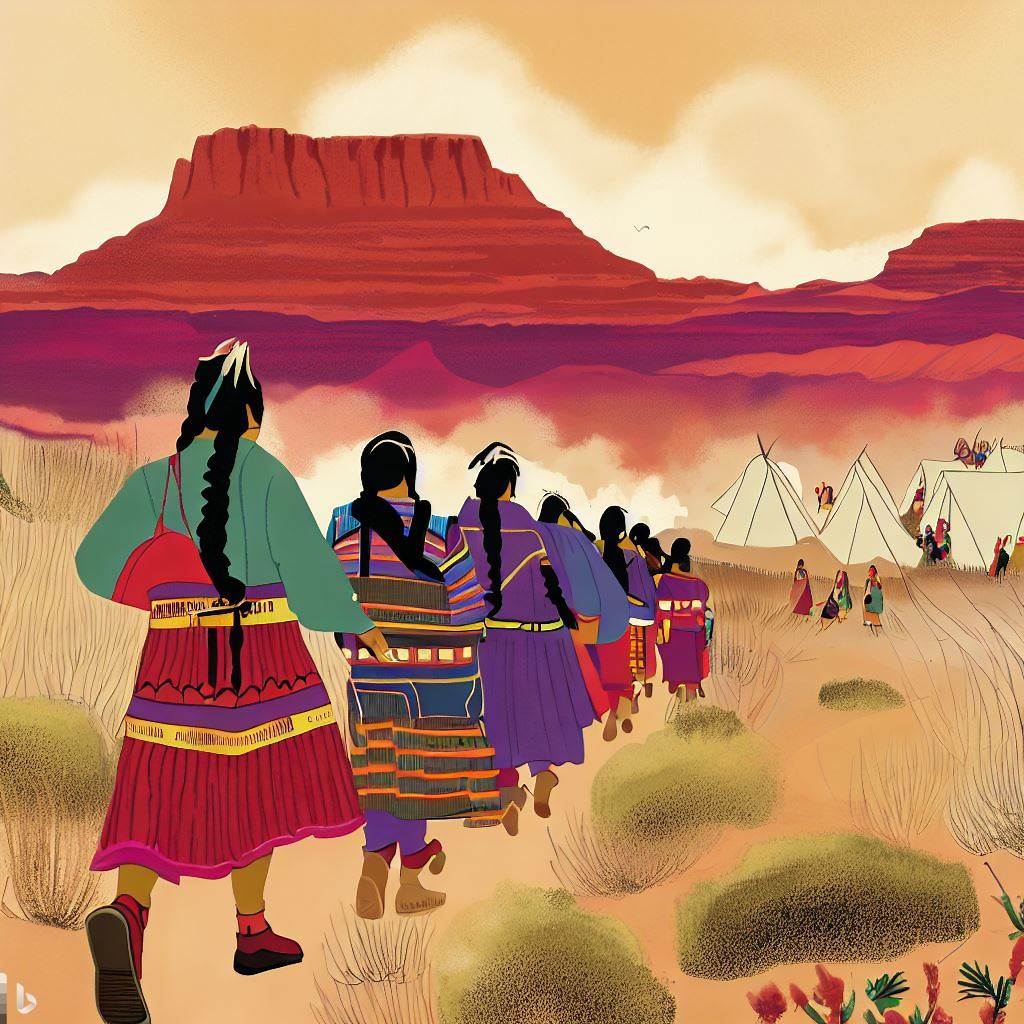

The wind whispers across the vast, arid landscapes of the American Southwest, carrying with it the echoes of a profound and painful history. For the Diné people, more commonly known as the Navajo, these winds tell a story not just of the land, but of an unimaginable journey—a forced exodus that etched itself into the very soul of a nation. This was the Long Walk, a harrowing series of forced marches in the mid-19th century that saw thousands of Navajo men, women, and children driven from their ancestral lands to a desolate internment camp, leaving a legacy of suffering, resilience, and an unbreakable bond with their homeland.

To understand the Long Walk is to understand the complex, often brutal, expansion of the United States. By the mid-1800s, American settlers were pushing relentlessly westward, fueled by the concept of Manifest Destiny and the allure of gold and new territories. The Navajo, a powerful and independent nation, occupied a vast and resource-rich territory spanning parts of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. Their traditional way of life, characterized by sheep herding, farming, and occasional raids (often in retaliation for raids by Mexican, Pueblo, and American forces), clashed directly with the ambitions of the burgeoning American republic.

The Seeds of Conflict and a "Final Solution"

The period leading up to the Long Walk was marked by escalating tensions. The U.S. military, having recently acquired the Southwest after the Mexican-American War, struggled to control the region. General James H. Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico, emerged as a central figure in this unfolding tragedy. A staunch believer in American expansion and a firm hand, Carleton viewed the Navajo as an impediment to progress and a constant source of regional instability. He envisioned a "final solution" to the "Navajo problem": their removal to a distant, isolated reservation where they could be "civilized" and controlled.

Carleton chose a site called Bosque Redondo, near Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico, over 300 miles from the heart of Navajo territory. His plan was simple, if brutal: starve the Navajo into submission, then march them to this barren outpost. He famously declared his intention to "gather them all together, settle them in a place where they can be looked after and remain in peace."

To execute his vision, Carleton enlisted the help of Colonel Christopher "Kit" Carson, a celebrated frontiersman. Carson, despite his previous friendly relations with some Navajo, was ordered to implement a scorched-earth policy. Beginning in the fall of 1863, Carson’s troops systematically destroyed Navajo homes, hogans, crops, orchards, and livestock. They poisoned wells and laid waste to everything that sustained life. The goal was not direct combat, but total deprivation.

The Scorched Earth and Forced Surrender

The winter of 1863-1864 was particularly harsh, and the destruction wrought by Carson’s forces proved devastating. Without food, shelter, or means of survival, thousands of Navajo faced a stark choice: surrender or starve. Many chose the former, emerging from their hidden canyons and mesas, desperate and broken.

"The soldiers would ride up on our hogans, and we would run into the brush and hide," recounted Navajo elder Annie Wauneka years later, recalling her parents’ stories. "They would burn our homes and destroy our crops. We had nothing left."

As groups surrendered, they were immediately rounded up and forced to begin the arduous trek to Bosque Redondo. It wasn’t a single, monolithic march, but a series of forced movements involving multiple groups over several months, each with its own unspeakable horrors.

The Arduous Journey: A Trail of Tears and Death

The Long Walk commenced in the spring of 1864. Over the next year, an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Navajo, along with some Mescalero Apache who had also been forcibly relocated, were driven across hundreds of miles of unforgiving terrain. The journey, typically 300 to 400 miles depending on the starting point, was a testament to human suffering.

The conditions were appalling. Men, women, children, and the elderly, many already weakened by starvation, were forced to walk at gunpoint, often in winter snows or blistering summer heat. They were given minimal food and water, often contaminated. Disease, particularly dysentery, smallpox, and pneumonia, ravaged the ranks. Those who fell behind, too weak or ill to continue, were often shot or left to die by the wayside. Babies were born on the trail, and many perished shortly after. Elders, unable to keep pace, were abandoned.

"Many of my people died on the way," recounted Chee Dodge, a future Navajo leader who made the Long Walk as a child. "We were given bad food, and water from dirty sources. Our people became weak and sick. Many were buried by the roadside."

The exact number of deaths is unknown, but estimates range from 2,000 to 3,000, representing a quarter to a third of the entire Navajo population at the time. The journey was so traumatic that it became known in Navajo as "Hwéeldi," a term that signifies a place of suffering and refers specifically to the Bosque Redondo internment.

Bosque Redondo: A Walled Prison

Upon arrival at Bosque Redondo, the nightmare continued. The U.S. government’s plan for the reservation was a catastrophic failure. The site itself was poorly chosen: the Pecos River water was alkaline, unfit for drinking, and caused severe stomach ailments. The soil was infertile, making agriculture nearly impossible. Crops repeatedly failed, leading to chronic food shortages. Firewood was scarce, forcing the Navajo to walk miles to gather scrub brush for warmth and cooking.

Disease, exacerbated by malnutrition and overcrowding, spread rapidly. Medical care was virtually nonexistent. The Navajo, accustomed to a vast, open landscape, were confined to a small, treeless area, surrounded by U.S. Army sentries. Their traditional spiritual practices, deeply tied to the land and ceremony, were suppressed.

Adding to the misery was the presence of the Mescalero Apache, traditional enemies of the Navajo, who had also been forcibly interned there. Tensions flared, leading to further conflict and misery. The U.S. government’s promise of providing seeds, tools, and a path to self-sufficiency proved hollow. The camp became a symbol of incompetence, neglect, and suffering.

"We cried every day for our homes," recalled Manuelito, one of the principal Navajo chiefs, later. "We looked to the east, but we could not see our sacred mountains. We were like birds in a cage."

The Turning Tide and the Treaty of 1868

The miserable conditions at Bosque Redondo could not be ignored indefinitely. The internment was not only a humanitarian disaster but also a financial drain on the U.S. government, costing over a million dollars annually to maintain a perpetually failing operation. Reports from military officers and Indian agents on the ground painted a grim picture of starvation, disease, and despair.

By 1868, the futility of the Bosque Redondo experiment was clear. General William Tecumseh Sherman and Samuel F. Tappan, representatives of the U.S. Indian Peace Commission, arrived to negotiate. They expected to offer the Navajo a new reservation, perhaps in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

But the Navajo leaders, particularly Chief Barboncito and Manuelito, were resolute. They refused to consider any land other than their homeland. Barboncito, speaking for his people, delivered a powerful and poignant plea:

"I hope to God you will not ask me to go to any other country except my own," he stated. "When we were first taken from our homes, we were told that we were to be taken to a country where there were trees and water… When we arrived here, we found it to be all barren and no wood… I hope you will return my people to their country… If we are left to suffer another four years, we will all die."

His words, steeped in a profound connection to the land, resonated. The Navajo’s unwavering demand to return to their ancestral territory, combined with the economic and logistical failures of Bosque Redondo, ultimately swayed the commissioners. On June 1, 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was signed, a unique document in U.S. history. Unlike most treaties that moved tribes further away, this one allowed the Navajo to return to a portion of their original lands, establishing the Navajo Nation reservation, the largest in the United States today.

The Return Home and a New Beginning

The journey back was filled with a mixture of joy and trepidation. They were returning home, but to a land stripped bare, their hogans burned, their fields destroyed. Yet, they walked with a renewed sense of purpose and hope. It took several months for all the Navajo to make the journey, covering the same distances, but this time, in the direction of freedom and rebuilding.

The Navajo faced immense challenges in rebuilding their lives. But their resilience, deeply rooted in their cultural values and spiritual connection to their land, proved indomitable. They re-established their herds, replanted their crops, and slowly, painstakingly, brought their nation back from the brink of annihilation.

A Living Legacy

The Long Walk remains a foundational event in Navajo history, a collective trauma that continues to impact generations. Its legacy is seen in the intergenerational trauma many Diné still carry, manifesting in various social and health challenges. Yet, it is also a testament to incredible resilience, survival, and the enduring power of cultural identity.

Navajo elders continue to share the stories of Hwéeldi, ensuring that the sacrifices and suffering are never forgotten. It serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of forced displacement and cultural suppression. But more profoundly, it is a story of triumph – of a people who, despite unimaginable hardship, refused to be broken, held onto their identity, and ultimately returned to rebuild their nation stronger than ever.

Today, the Navajo Nation thrives, a vibrant and proud people who carry the lessons of the Long Walk in their hearts. The wind across their land still whispers, but now it carries not just the echoes of suffering, but also the enduring spirit of survival, the profound love of home, and the unbreakable will of the Diné.