The Vanishing Horizon: A History of Native American Land Loss

From the vast, unbroken expanse of their ancestral lands, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, to the fragmented, often isolated parcels they inhabit today, the story of Native American land loss is a foundational, yet frequently understated, chapter in the history of the United States. It is a narrative woven with broken treaties, forced removals, legislative maneuvers, and the relentless march of a nation built on expansion, leaving behind a legacy of profound dispossession and an enduring struggle for justice.

Before the arrival of European colonists, indigenous peoples held dominion over an entire continent. Their relationship with the land was not one of ownership in the European sense, but rather of stewardship, a sacred trust deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs, cultural practices, and subsistence. Rivers, forests, mountains, and plains were not commodities to be bought and sold, but living entities, integral to their identity and survival. This fundamental philosophical divide – communal stewardship versus individualistic ownership and exploitation – set the stage for centuries of conflict.

The Doctrine of Discovery and Early Encroachment

The seeds of dispossession were sown almost immediately with the arrival of Europeans. Fueled by imperial ambitions and a belief in their own cultural and religious superiority, colonizers invoked the "Doctrine of Discovery," a legal concept originating from 15th-century papal bulls. This doctrine asserted that Christian European nations had the right to claim lands inhabited by non-Christians, extinguishing the indigenous inhabitants’ title to the land while retaining their "right of occupancy." It was a legal fiction that provided the moral and legal justification for conquest and seizure, effectively rendering Native sovereignty subservient to colonial claims.

Early interactions often involved a mix of diplomacy, trade, and outright violence. As European settlements grew, so did their hunger for land. Initial treaties, often hastily drafted and poorly understood by Native leaders, typically involved the exchange of vast territories for European goods or promises. These agreements were frequently violated by the colonists, who simply pushed further into Native lands as their populations expanded. Disease, brought by Europeans, also played a devastating role, decimating Native populations and weakening their ability to resist encroachment.

The Post-Revolutionary Era: A New Nation, Old Ambitions

Following the American Revolution, the nascent United States inherited the British policy of treating Native American nations as sovereign entities through treaties. However, this recognition was often a thinly veiled means to an end: acquiring land. The new nation, eager to expand westward, viewed Native lands as obstacles to progress and prosperity. Early federal policy, influenced by figures like George Washington and Henry Knox, sought to "civilize" Native Americans by encouraging them to adopt farming, Christianity, and private land ownership, believing this would make them easier to assimilate and, crucially, free up their traditional hunting grounds for white settlement.

But the pace of westward migration soon outstripped these assimilationist policies. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 dramatically expanded the nation’s territorial claims, intensifying the pressure on Native lands in the Southeast. The War of 1812, which saw some Native nations ally with the British, further fueled American resentment and distrust, hardening attitudes towards indigenous peoples.

The Era of Forced Removal: "Trail of Tears" and Beyond

The early 19th century culminated in one of the darkest chapters of Native American land loss: the policy of forced removal. By the 1820s, the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – had adopted many aspects of American culture, including written languages, constitutional governments, and farming techniques. Yet, their presence on valuable cotton-growing lands in the Southeast was intolerable to land-hungry white settlers, particularly in Georgia.

President Andrew Jackson, a staunch advocate of removal, signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. This legislation authorized the forced relocation of Native Americans from their ancestral lands east of the Mississippi River to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Despite the Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) – which sided with the Cherokee Nation, affirming their sovereignty and declaring Georgia’s laws unconstitutional within Cherokee territory – President Jackson famously defied the ruling, allegedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it."

The result was the infamous "Trail of Tears" (1838-1839), the forced march of the Cherokee Nation, along with other tribes, in which thousands perished from disease, starvation, and exposure. It was a brutal act of ethnic cleansing that solidified the principle that Native land rights were secondary to the desires of white expansion. This period saw the loss of millions of acres and the decimation of entire populations, fundamentally reshaping the demographic and geographic landscape of the continent.

Manifest Destiny and the Indian Wars

As the nation embraced the concept of "Manifest Destiny" – the belief in America’s divine right to expand across the North American continent – the pressure on Native lands intensified exponentially. The California Gold Rush of 1849, the construction of transcontinental railroads, and the Homestead Act of 1862 all spurred massive westward migration, bringing settlers into direct conflict with the Plains tribes.

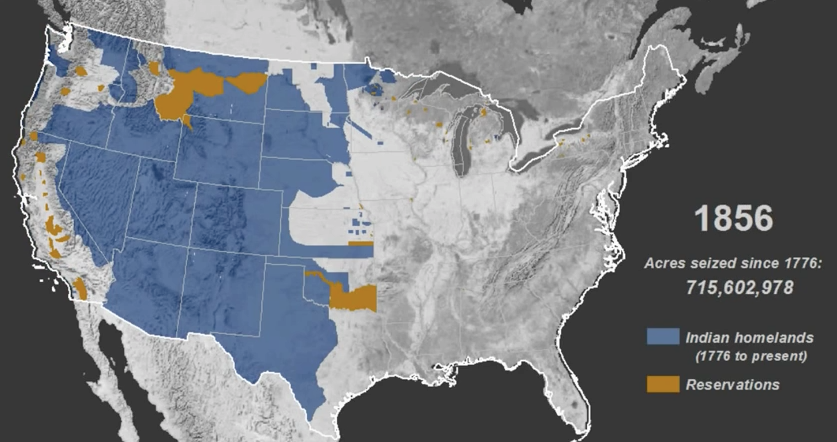

The mid to late 19th century was marked by a series of brutal "Indian Wars." Tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Apache, and Comanche fiercely resisted the encroachment on their traditional hunting grounds and sacred sites. Battles such as Little Bighorn (1876), where Lakota and Cheyenne warriors annihilated Custer’s 7th Cavalry, became legendary acts of Native resistance. However, superior American military technology, combined with the deliberate extermination of the buffalo – the lifeblood of the Plains tribes – ultimately broke their resistance. The Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered, marked the tragic end of major armed conflict and symbolized the complete subjugation of Native peoples.

By this point, the vast majority of Native land had been seized through a combination of treaties (often fraudulent or coerced), executive orders, and military force. What remained were often fragmented reservations, remnants of once-expansive territories.

The Allotment Era: Breaking Up Communal Lands

Even the reservation system, flawed as it was, did not satisfy the land hunger of the United States. The late 19th century saw a new strategy emerge, ostensibly aimed at "civilizing" Native Americans but effectively designed to further diminish their land base: the General Allotment Act, or Dawes Act, of 1887.

This act mandated the breakup of communally held tribal lands into individual allotments, typically 80 to 160 acres per head of household. The stated goal was to encourage individual farming and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society by instilling the concept of private property. However, the true devastating impact lay in the "surplus" lands. After allotments were made, millions of acres of tribal land were declared "surplus" and opened up for sale to non-Native settlers and corporations.

The Dawes Act was catastrophic. Between 1887 and 1934, Native American landholdings plummeted from 138 million acres to just 48 million acres – a loss of nearly two-thirds of their remaining land base. The policy also created a complex "checkerboard" pattern of land ownership on reservations, making unified tribal governance and economic development incredibly difficult. It shattered communal structures, disrupted traditional economies, and plunged many Native families into poverty.

A Shifting Tide and Ongoing Struggles

The disastrous consequences of the Dawes Act eventually led to a policy reversal. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, often called the "Indian New Deal," ended the allotment policy, encouraged tribal self-governance, and initiated some limited land consolidation. While a significant step, it did little to restore the vast tracts of land that had been lost.

The mid-20th century saw new challenges with the "Termination" policy (1950s-1960s), which aimed to dismantle tribes as legal entities and end federal responsibility for Native Americans, leading to further land loss and poverty for terminated tribes. However, the subsequent "Self-Determination" era, beginning in the 1970s, marked a renewed commitment to tribal sovereignty and self-governance, empowering tribes to manage their own affairs and reclaim some control over their lands.

Today, the legacy of land loss continues to profoundly impact Native American communities. Many tribes are still fighting for the return of ancestral lands, for compensation for historical injustices, and for the protection of sacred sites. The "Land Back" movement, gaining increasing momentum, seeks to restore indigenous sovereignty and control over ancestral territories, recognizing that true justice involves not just recognition but material restitution.

The history of Native American land loss is not merely a tale of historical injustice; it is a living legacy that shapes contemporary issues of poverty, health disparities, environmental justice, and cultural preservation. It underscores the profound cost of expansion driven by greed and a disregard for indigenous rights. Understanding this history is crucial, not just to acknowledge past wrongs, but to inform ongoing efforts towards reconciliation, respect, and a more just future for all inhabitants of this continent. The vanishing horizon of ancestral lands may represent a past tragedy, but the enduring resilience and ongoing fight for self-determination by Native nations offer a beacon of hope for a future built on equity and genuine partnership.