The Rock Reclaimed: How Native Americans Occupied Alcatraz and Ignited a Movement

For decades, Alcatraz Island stood as an unyielding symbol of incarceration, its stark silhouette against the San Francisco Bay a chilling testament to federal power. From 1934 to 1963, "The Rock" housed America’s most dangerous criminals, an inescapable fortress of despair. But in the late 1960s, this grim icon was unexpectedly transformed, not into another federal prison, but into a beacon of hope, defiance, and a rallying point for a long-suppressed people.

On November 20, 1969, a group of Native American activists, calling themselves the "Indians of All Tribes" (IAT), launched an audacious occupation of the abandoned federal prison island. Their act was not one of criminality, but of sovereignty and protest, echoing centuries of broken promises and demanding recognition for indigenous rights. This 19-month occupation, which lasted until June 11, 1971, would become a pivotal moment in the burgeoning Red Power movement, forever altering the landscape of Native American activism and U.S. federal Indian policy.

The Seeds of Discontent: A Legacy of Broken Treaties

The occupation did not spring from a vacuum. It was the culmination of generations of systemic oppression, land dispossession, and assimilation policies that had ravaged Native American communities. By the mid-20th century, many indigenous peoples lived in dire poverty, their cultures under assault, and their voices unheard. The U.S. government’s "termination policy" of the 1950s and 60s, which aimed to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society, only exacerbated these grievances, leading to widespread displacement and cultural loss.

Against this backdrop, a new generation of Native American activists began to emerge, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and a growing sense of shared identity and purpose. They sought to reclaim their heritage, assert their sovereignty, and demand justice for historical wrongs. Alcatraz, abandoned since 1963 and deemed "surplus federal property," presented a unique opportunity.

The legal justification for the occupation was rooted in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which stipulated that all abandoned or unused federal land should be returned to the Native American people. Though the treaty specifically referred to the Sioux Nation, the occupiers argued its spirit applied broadly to all indigenous peoples and their inherent rights to ancestral lands. As Adam Fortunate Eagle, an Ojibwa activist who helped plan the initial landings, famously put it, "We were going to claim Alcatraz because it was rock, and we were rock. And we were going to make it into a symbol."

The Initial Landings: "We Hold the Rock!"

The idea of occupying Alcatraz had been floated for years, with several smaller, unsuccessful attempts in the mid-1960s. However, it was the determined leadership of students and activists, many from the Bay Area’s urban Indian community, that finally brought the plan to fruition. Richard Oakes, a charismatic Mohawk student from San Francisco State University, emerged as a prominent figure.

On November 9, 1969, a small group of activists, including Oakes, made a brief landing on the island, planting an American Indian Movement (AIM) flag and issuing a mock "Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People." This initial foray was quickly thwarted by the Coast Guard, but it served as a powerful declaration of intent.

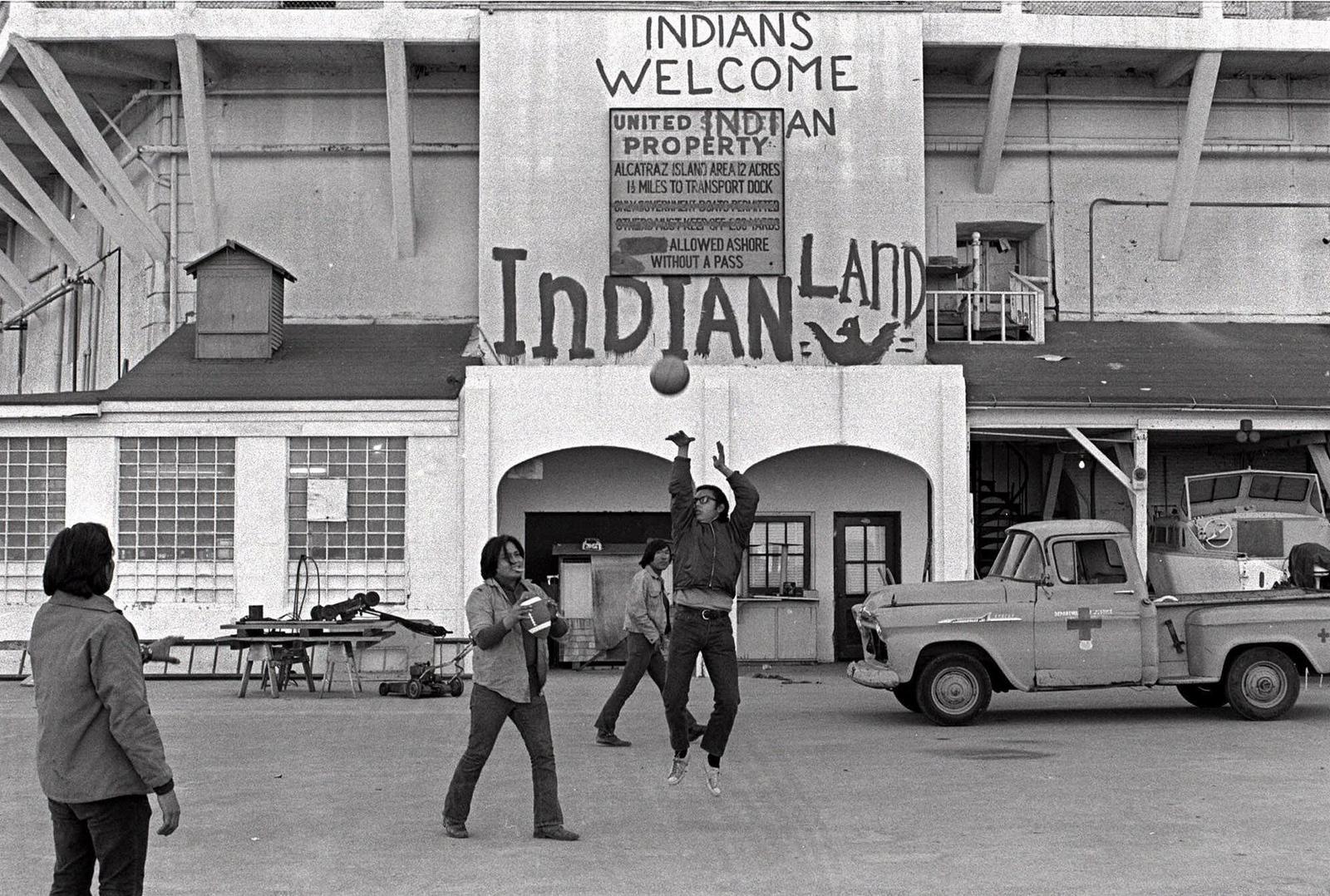

Eleven days later, in the pre-dawn hours of November 20, 1969, a larger, more determined group of 89 Native Americans, including students, elders, and families, successfully landed on Alcatraz. They arrived in boats like the Monte Cristo, braving the choppy waters of the bay and eluding Coast Guard patrols. Upon setting foot on the island, they declared it "Indian Land." "We hold the Rock!" became their rallying cry.

Life on the Island: A Nation Reborn

In the early days of the occupation, Alcatraz became a vibrant, self-governing community. The occupiers, representing dozens of different tribes, established a governing council, set up a school for their children, and even launched a radio station, "Radio Free Alcatraz," broadcasting their message to the world. They repaired dilapidated buildings, set up communal kitchens, and created a sense of shared purpose.

Their "Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People," witty and sharply satirical, offered to buy Alcatraz for "$24 in glass beads and red cloth," mocking the infamous purchase of Manhattan Island. It highlighted the desolate conditions on the island, comparing them to the impoverished reservations where many Native Americans were forced to live: "We can use the abandoned prison facilities in the following manner: 400 Indian people can be better housed here than on any Indian reservation… It has no running water, no sanitation facilities, no electricity, no fishing, hunting, trapping, or farming areas; no health care facilities; no industry; and a population that has always been held prisoner and dependent upon unsympathetic jailers. We feel that this, therefore, would be a most suitable reservation for the White Man."

The occupation quickly garnered national and international attention. Celebrities like Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn, and Dick Gregory visited the island, lending their support and resources. Media outlets flocked to the scene, eager to cover this unprecedented act of civil disobedience. The occupiers’ message resonated with many Americans who were increasingly critical of government policies and sympathetic to the struggles of marginalized groups.

John Trudell, a Santee Sioux activist and powerful orator, became the voice of Radio Free Alcatraz, his broadcasts articulating the historical grievances and future aspirations of Native Americans. LaNada Means, a Shoshone-Bannock student and one of the initial planners, played a crucial role in organizing the initial landing and sustaining the community.

Challenges and Decline: The Fraying Edges of Unity

Despite the initial euphoria and widespread support, life on Alcatraz was undeniably harsh. The island lacked fresh water, electricity, and adequate shelter. Food and medical supplies were scarce, reliant on precarious supply runs often thwarted by the Coast Guard. The federal government, under President Richard Nixon, adopted a strategy of containment rather than direct confrontation, hoping the occupation would fizzle out on its own. They cut off utilities, increased Coast Guard patrols, and began to remove non-Native supporters from the island.

As the months wore on, the initial unity began to fray. Internal disagreements over leadership, strategy, and the role of non-Native participants emerged. The harsh conditions took their toll. Drug and alcohol use became problems. Tragically, in January 1970, Richard Oakes’ 12-year-old stepdaughter, Yvonne, fell to her death from a decaying building, a devastating blow to the community. In October 1970, John Trudell’s wife, Tina, their two children, and his mother-in-law died in a suspicious house fire on their reservation, an event many attributed to government retaliation, though never proven. These tragedies, combined with waning media attention and increasing government pressure, eroded morale.

By early 1971, the population on the island had dwindled significantly from its peak of over 400. The federal government, eager to end the standoff, intensified its efforts.

The End of the Occupation and Its Enduring Legacy

On June 11, 1971, federal marshals, FBI agents, and Coast Guard personnel raided Alcatraz. They found only 15 people remaining on the island. The occupation ended peacefully, without violence, as the remaining occupiers were escorted off The Rock.

While the occupation of Alcatraz did not result in the island being returned to Native American control, its impact was profound and far-reaching. It succeeded in:

- Raising Awareness: The occupation catapulted Native American issues into the national consciousness, forcing mainstream America to confront the historical injustices faced by indigenous peoples.

- Inspiring Activism: Alcatraz became a powerful symbol and a catalyst for the broader Red Power movement. It inspired numerous other protests and occupations, including the takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington D.C. in 1972 (the "Trail of Broken Treaties") and the Wounded Knee occupation in 1973.

- Shifting Federal Policy: The Nixon administration, responding to the growing visibility of Native American issues, began to move away from the disastrous termination policies. In 1970, Nixon delivered a landmark speech calling for a new era of "self-determination without termination." This eventually led to the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which granted tribal governments greater control over their own affairs and federal programs.

- Fostering Cultural Pride: The occupation reignited a sense of pride and cultural identity among Native Americans across the country, encouraging a revitalization of traditional languages, ceremonies, and arts. It demonstrated the power of collective action and the resilience of indigenous peoples.

Today, Alcatraz Island remains a national park, a popular tourist destination. Yet, the memory of the Native American occupation endures. Plaques and exhibits on the island acknowledge this pivotal period, ensuring that visitors understand its significance beyond merely being a former prison. The water tower on Alcatraz, famously spray-painted with "INDIAN LAND," stands as a permanent, albeit fading, reminder of the 19-month struggle for sovereignty.

The occupation of Alcatraz was a bold, unprecedented act that transformed a symbol of confinement into a beacon of freedom and self-determination. It may not have achieved its immediate goal of reclaiming the land, but it undeniably changed the course of Native American history, setting the stage for greater autonomy, cultural resurgence, and a continuing fight for justice that resonates to this day. Alcatraz, once a fortress of despair, was briefly transformed into a vibrant, if embattled, symbol of hope and defiance, forever etching the story of Native American resilience into the very stone of "The Rock."