The Unseen Architects: How Native American Children Shaped History

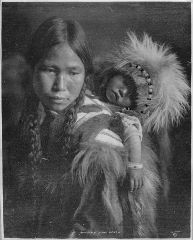

History, often meticulously documented through the deeds of adults, frequently overlooks the profound and multifaceted roles played by children. Yet, within Native American societies, children were not merely passive recipients of culture or future adults in waiting; they were active, integral participants whose presence, education, contributions, and resilience profoundly shaped the trajectory of their communities and, by extension, the broader American narrative. From the ancient traditions of holistic learning to the brutal crucible of assimilation and the modern movement of cultural revitalization, Native American children have always been, and remain, unseen architects of history.

I. The Foundations of Being: Children in Traditional Native American Societies

Before the arrival of European colonizers, the lives of Native American children were rich tapestries woven with purpose, belonging, and profound connection to their environment and spiritual beliefs. Unlike European models of childhood that often segregated children from adult responsibilities, Native American societies integrated children into the fabric of daily life from a very young age.

Education as Lived Experience:

Learning was not confined to formal settings but was an immersive, lifelong process. Children learned primarily through observation, imitation, and direct participation. Elders, aunts, uncles, and even older siblings served as teachers, imparting knowledge through storytelling, practical demonstration, and gentle guidance. A young Ojibwe boy, for instance, might learn tracking by accompanying his father on hunts, observing how to read animal signs, set snares, or identify edible plants. A Navajo girl would sit beside her grandmother, learning the intricate patterns of weaving or the delicate art of pottery by watching, then trying her hand with smaller, simpler pieces.

This experiential learning fostered a deep understanding of their natural world, their community’s economic systems, and their spiritual cosmology. Children were taught to respect all living things, to understand the interconnectedness of nature, and to live in harmony with the land. Oral traditions, myths, and legends, often told around a fire, served as vital educational tools, transmitting history, moral lessons, and cultural values across generations. These stories not only entertained but also instilled a sense of identity and belonging, connecting children to their ancestors and their future responsibilities.

Early Contributions and Responsibilities:

Children were considered valuable members of the community, and their contributions, however small, were recognized and appreciated. As soon as they were able, they were given age-appropriate tasks that directly benefited their families and tribes. Younger children might gather firewood, fetch water, or help tend to younger siblings. As they grew, their responsibilities expanded: boys might learn to carve tools, fashion bows, or assist in communal hunts; girls would help prepare food, cure hides, or gather medicinal plants.

This early integration into communal labor instilled a strong work ethic, a sense of responsibility, and an understanding of their vital role in the collective survival and prosperity of the group. It also fostered self-reliance and competence, preparing them for adult roles. The famous Sioux proverb, "Children are the strength of the nation," encapsulates this philosophy, highlighting that the well-being and future of the tribe rested squarely on the shoulders of its youth.

Spiritual and Cultural Guardians:

Beyond practical skills, children were also crucial in the transmission of spiritual practices and cultural identity. They participated in ceremonies, learned traditional songs and dances, and were taught the sacred stories and rituals of their people. In many societies, children were seen as closer to the spirit world, embodying innocence and purity, and were sometimes involved in healing rituals or vision quests as they approached adolescence. They were the living vessels through which language, customs, and spiritual knowledge would pass into the future, ensuring the continuity of their distinct cultural heritage.

II. The Crucible of Change: Children in the Era of Colonialism and Displacement

The arrival of European colonizers irrevocably shattered the traditional rhythms of Native American life, and children bore a disproportionate share of the resulting devastation. They became targets, victims, and, at times, unwitting agents in the unfolding drama of conquest and resistance.

The Invisible Enemy: Disease:

Perhaps the most devastating impact came from diseases – smallpox, measles, influenza – to which Native Americans had no immunity. These epidemics swept through communities like wildfire, decimating populations. Children, with their developing immune systems, were often the most vulnerable. Villages were left with few adults, and countless children became orphans, left to fend for themselves or adopted into other, often struggling, families. The loss of entire generations of children had profound long-term effects, eroding cultural memory, breaking down social structures, and creating deep, intergenerational trauma.

Warfare, Displacement, and Survival:

As colonial expansion intensified, Native American children found themselves on the front lines of conflict and displacement. They witnessed brutal massacres, endured forced marches like the Cherokee’s “Trail of Tears,” and were often captured and enslaved. In the chaos of war, children sometimes played roles as messengers, lookouts, or even active combatants as they grew older, fighting for their very survival and the preservation of their families. Their resilience in the face of such unimaginable hardship is a testament to the human spirit.

The Assimilation Agenda: Boarding Schools:

Perhaps the most insidious and long-lasting attack on Native American children came in the form of forced assimilation through the boarding school system. Beginning in the late 19th century and continuing well into the 20th, institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt, operated under the chilling philosophy: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Native American children, some as young as five or six, were forcibly removed from their families and communities, often against their parents’ will. They were transported far from their homes, stripped of their traditional clothing, had their hair cut short (a deeply significant act in many cultures), and were forbidden to speak their native languages or practice their cultural traditions. They were given new, Anglo-American names and subjected to harsh discipline, forced labor, and often, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

The goal was to erase their Native identity and indoctrinate them into white American society. Children were taught English, vocational skills (often menial labor), and Christian doctrine. The impact was catastrophic: generations of children grew up without their families, without their languages, without their traditional knowledge. Many suffered severe psychological trauma, leading to intergenerational cycles of abuse, addiction, and cultural disconnection.

Yet, even within these oppressive walls, children displayed remarkable resilience. They secretly spoke their languages, shared stories, formed bonds with fellow students, and found ways to preserve fragments of their identity. These acts of quiet resistance, though often met with punishment, were vital threads in the tapestry of cultural survival. The boarding school experience, while a dark chapter, also forged a generation of activists who would later fight for Native rights and cultural reclamation.

III. Resilience, Rebirth, and the Future: Children in Modern Native America

The legacy of historical trauma continues to affect Native American communities, manifesting in disparities in health, education, and economic well-being. However, the story of Native American children in the 20th and 21st centuries is also one of profound resilience, cultural revitalization, and an unwavering commitment to a brighter future.

Reclaiming Identity and Language:

In recent decades, there has been a powerful movement to reclaim and revitalize Native American languages and cultural practices. Children are at the heart of this movement. Immersion schools, language camps, and intergenerational programs are teaching younger generations their ancestral languages, songs, dances, and ceremonies. These initiatives are not just about preserving the past; they are about healing historical wounds, strengthening identity, and building a foundation for future generations.

For example, the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, initiated by Jessie Little Doe Baird, a Mashpee Wampanoag tribal member, has successfully brought the Wampanoag language back from extinction through immersion programs for children. Children are now speaking a language that hasn’t been spoken in generations, becoming fluent speakers and carrying the torch of their cultural heritage forward.

Advocacy and Leadership:

Today’s Native American youth are increasingly becoming powerful advocates for their communities and the environment. They are speaking out on issues ranging from climate change and land rights to social justice and the protection of sacred sites. Youth councils, leadership programs, and social media platforms provide avenues for their voices to be heard, demonstrating that the future leaders are already actively shaping the present. They are challenging stereotypes, educating the public, and demanding recognition and justice for their people.

Navigating Two Worlds:

Modern Native American children often navigate a complex duality, balancing their traditional heritage with the demands of contemporary society. They attend mainstream schools, use technology, and participate in global culture, while simultaneously learning their tribal histories, participating in ceremonies, and upholding their cultural values. This ability to walk in two worlds, drawing strength from both, is a unique and powerful aspect of their identity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Young

The role of Native American children throughout history is far more profound than often acknowledged. In traditional societies, they were vital learners, contributors, and spiritual custodians, ensuring the continuity of their cultures. In the face of colonialism, disease, and the devastating assimilation policies of boarding schools, they endured unimaginable hardship, often becoming unwilling symbols of a culture under siege. Yet, even in the darkest hours, their resilience, their quiet acts of resistance, and their sheer will to survive laid the groundwork for future generations.

Today, Native American children are at the forefront of a vibrant cultural renaissance, reclaiming their languages, traditions, and narratives. They are not just the inheritors of a complex past but active agents shaping a hopeful future. To truly understand American history, one must look beyond the dominant narratives and recognize the indispensable, often unseen, contributions of Native American children – the silent witnesses, the resilient survivors, and the enduring architects of their people’s story. Their journey is a testament to the enduring power of identity, family, and the unbroken spirit of a people.