The Unsung Architects: Unveiling the Enduring Roles of Native American Women in History

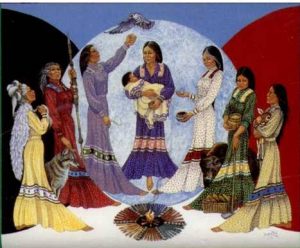

For too long, the narrative of Native American history has been dominated by the figures of male warriors, chiefs, and hunters, often framed through the lens of Eurocentric perspectives. Yet, beneath the surface of these commonly told tales lies a profound and multifaceted truth: Native American women were, and continue to be, the unsung architects of their societies, the bedrock of their cultures, and the resilient guardians of their heritage. Their roles, diverse and dynamic across hundreds of distinct nations, transcended simple domesticity, encompassing immense spiritual, economic, political, and social power.

To understand their historical significance, one must first dismantle the pervasive stereotypes that have often reduced Indigenous women to passive figures or romanticized Pocahontas-like characters. The reality is far richer and more complex, revealing women who were powerful decision-makers, skilled producers, revered healers, and formidable cultural transmitters.

Pillars of Society: Matrilineal Foundations and Economic Power

In many, though not all, Indigenous societies across North America, social structures were often matrilineal or matrilocal. Unlike European patriarchal systems where lineage and property passed through the father, in matrilineal societies, descent was traced through the mother’s line. This meant that women held significant power regarding family identity, inheritance, and the naming of children. Matrilocal societies further reinforced this, with husbands moving into their wives’ family homes upon marriage, centralizing the woman’s family as the core unit.

The Iroquois Confederacy, a powerful and influential league of nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later Tuscarora), provides a prime example of this matriarchal influence. Here, Clan Mothers were not just respected elders; they were the true political backbone. They held the authority to nominate male chiefs, advise them, and even depose them if they failed to act in the best interests of the community. As historian Gail P. Landsman notes, "Iroquois women’s power was not based on individual achievement but on their collective position as the ‘mothers of the nation,’ the givers of life, and the controllers of the means of production." This inherent connection to life-giving and food production gave them immense leverage.

Economically, Indigenous women were often the primary food producers and resource managers. While men were typically hunters, women were the cultivators, gatherers, and processors of food. In agricultural societies, such as those of the Pueblo, Cherokee, and Iroquois, women were the farmers, responsible for planting, tending, and harvesting staple crops like corn, beans, and squash – often known as the "Three Sisters" due to their symbiotic growing relationship. This control over the food supply meant they held significant economic power, often owning the fields and the harvests.

Beyond agriculture, women were skilled gatherers of wild plants, berries, nuts, and medicinal herbs, possessing extensive botanical knowledge passed down through generations. They processed hides, wove baskets, crafted pottery, and made clothing, often creating intricate and beautiful items that were both functional and imbued with cultural meaning. Their labor was not just essential for survival; it was the foundation of their communities’ economic stability and well-being.

Spiritual Guides and Healers: Keepers of Knowledge

The spiritual lives of Native American communities were deeply intertwined with the roles of women. Women were often revered as conduits to the spiritual world, embodying the life-giving forces of the earth and the universe. They participated in, and sometimes led, sacred ceremonies, rituals, and healing practices. Many women became skilled healers, or "medicine women," possessing profound knowledge of medicinal plants, remedies, and spiritual healing techniques. Their understanding of the human body and the natural world was holistic, connecting physical ailments to spiritual or emotional imbalances.

In many creation stories and oral traditions, female deities or ancestral figures played central roles, highlighting the sacredness of womanhood and the feminine principle. Women were also the primary storytellers and knowledge keepers, responsible for transmitting tribal histories, myths, and values to younger generations. Through songs, dances, and oral narratives, they ensured the continuity of cultural identity and traditional wisdom. This role was particularly crucial in societies without written languages, making women living libraries of their people’s heritage.

Political Influence and Diplomatic Prowess: Beyond the Council Fire

While European observers often failed to recognize it, Native American women wielded considerable political influence, even in societies not strictly matrilineal. They served as advisors to chiefs and councils, their opinions carrying significant weight due to their wisdom, experience, and economic contributions. In some nations, women’s councils existed parallel to men’s, with the power to veto decisions made by male leaders.

Figures like Sacagawea, though often romanticized, played a crucial diplomatic role during the Lewis and Clark expedition. Her presence as a Shoshone woman with an infant signaled peaceful intentions to other tribes and allowed the expedition to navigate dangerous territories and negotiate for supplies. While her personal story is complex and often misrepresented, her function as an interpreter and cultural intermediary was vital.

Less known but equally significant were the countless Indigenous women who acted as negotiators, peacekeepers, and strategists during times of conflict and diplomacy, often striving to maintain stability and prevent bloodshed. Their influence was not always overt or formal in a Western sense, but it was deeply embedded in the fabric of community decision-making.

Resilience and Resistance: Confronting Colonization

The arrival of European colonizers brought devastating changes that severely impacted the status and roles of Native American women. European patriarchal systems, which viewed women as property or subservient, clashed violently with Indigenous traditions of gender complementarity and female authority. Missionaries and government policies actively sought to dismantle Indigenous social structures, forcing women into restrictive domestic roles, often undermining their economic power, spiritual leadership, and political influence.

The imposition of patrilineal inheritance, the disruption of traditional economies, and the forced assimilation policies (like residential schools that separated children from their mothers and cultures) directly targeted the foundational roles of Indigenous women. This led to a profound loss of status and, in many cases, intergenerational trauma that continues to affect communities today.

However, despite these relentless assaults, Native American women demonstrated extraordinary resilience and resistance. They became the primary preservers of language, ceremonies, and traditional knowledge, often secretly passing down cultural practices even under threat of punishment. They led acts of spiritual and cultural resistance, nurturing their communities’ identities in the face of immense pressure to assimilate. Their strength and determination were crucial in ensuring that Indigenous cultures survived.

A Continuing Legacy: Modern Day Voices and Struggles

Today, the legacy of Native American women continues to shape contemporary Indigenous communities. They are at the forefront of movements for self-determination, environmental protection, and social justice. Indigenous women are increasingly visible as leaders in politics, academia, arts, and activism, reclaiming their historical roles and challenging ongoing injustices.

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement is a stark and painful reminder of the historical vulnerability and ongoing violence faced by Indigenous women and girls in North America. This crisis, rooted in historical trauma, systemic racism, and the erosion of Indigenous sovereignty, highlights the urgent need to address the continued marginalization and endangerment of Indigenous women. The MMIW movement, largely led by Indigenous women themselves, seeks justice, accountability, and the restoration of safety and dignity for their communities.

In essence, Native American women have always been the anchors of their societies – the protectors of land, language, and future generations. Their historical roles were not merely supplemental but fundamental to the survival, flourishing, and spiritual well-being of their nations. Recognizing their profound contributions is not just about correcting historical oversights; it is about understanding the full, vibrant tapestry of human history and acknowledging the enduring power and resilience of Indigenous womanhood. Their story is one of strength, wisdom, and an unwavering commitment to their people, a story that continues to unfold with power and purpose in the modern world.