Divided Loyalties, Enduring Legacy: The Complex Role of Native Americans in the Civil War

When we envision the American Civil War, images of Union blue clashing with Confederate gray often dominate our historical memory. Yet, this defining conflict was fought on more fronts than Gettysburg or Vicksburg, and by more actors than just white Americans. Far from being passive bystanders, Native American nations were deeply entangled in the war, their participation driven by complex motives of survival, self-determination, and the bitter legacy of broken treaties. Their story, often overlooked, reveals a hidden chapter of the Civil War, characterized by divided loyalties, internal strife, and a profound impact on their future.

The primary arena for Native American involvement was the Indian Territory, a vast expanse of land west of Arkansas that today largely comprises Oklahoma. This territory was home to the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole—who had been forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States during the infamous Trail of Tears in the 1830s. These tribes had established sophisticated governments, written constitutions, schools, and even adopted aspects of Southern culture, including, for some, the practice of chattel slavery. Their forced relocation had left a deep-seated distrust of the U.S. federal government, making them particularly vulnerable to the political machinations of the impending war.

The Pull of the Confederacy

As the Southern states seceded, Confederate agents quickly moved to secure alliances with the Native American nations in the Indian Territory. The Confederacy offered what the U.S. government often had not: promises of protection, respect for their lands and sovereignty, and the continuation of annuities (payments for ceded lands). For tribes like the Choctaw and Chickasaw, who had strong cultural and economic ties to the South, and whose leaders often owned enslaved people, the decision to align with the Confederacy seemed pragmatic. They shared a common interest in states’ rights and a belief in the institution of slavery.

The Cherokee Nation, the largest and most politically complex of the Five Tribes, was initially divided. Principal Chief John Ross advocated for neutrality, believing it was the only way to preserve his nation. However, a significant faction, led by Elias C. Boudinot and the formidable Stand Watie, argued for an alliance with the Confederacy. Watie, a veteran of the Cherokee removal and a fierce advocate for his people, believed that the Union, preoccupied with its own internal struggle, would offer no protection against Confederate encroachment or renewed attempts at land grabs.

Ultimately, the Confederacy’s proximity, its overtures, and the lingering resentment against the U.S. government’s past betrayals proved decisive for many. By late 1861, most of the Five Civilized Tribes had signed treaties with the Confederate States of America. These treaties recognized tribal sovereignty, promised representation in the Confederate Congress, and guaranteed annuities, often exceeding what the U.S. government had previously provided. Native American regiments were raised, equipped, and trained, fighting alongside their Confederate allies.

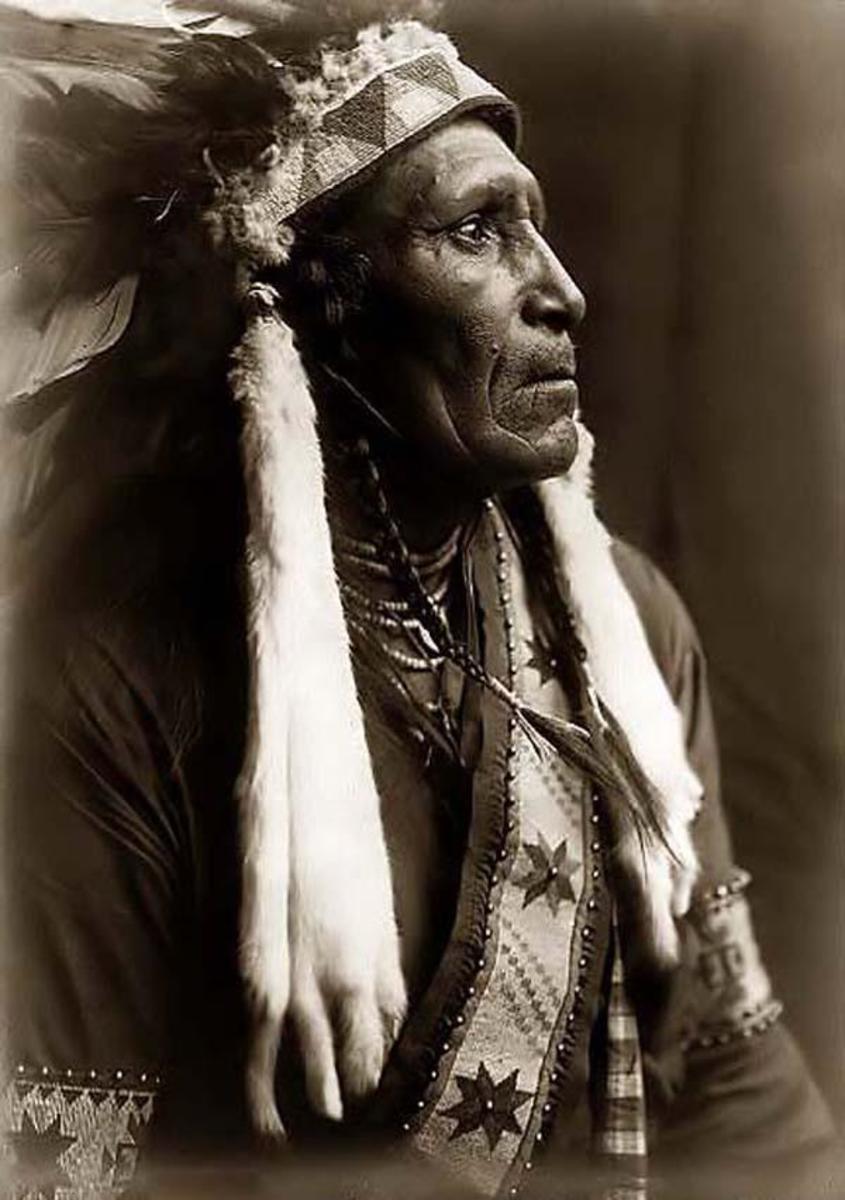

Stand Watie, a brilliant military tactician, rose through the Confederate ranks, eventually becoming the only Native American brigadier general in the war. His First Cherokee Mounted Rifles became legendary for their fierce fighting, effective guerilla tactics, and deep knowledge of the territory. They participated in major engagements such as the Battle of Pea Ridge (Arkansas, 1862), where Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw troops fought alongside Confederate forces. Watie’s command continued to harass Union supply lines and patrols throughout the war, becoming a persistent thorn in the Union’s side. In a poignant testament to his tenacity, Stand Watie was the last Confederate general to officially surrender, laying down his arms on June 23, 1865, more than two months after Robert E. Lee.

The Union’s Native American Allies

While many tribes sided with the Confederacy, not all Native Americans chose that path. For some, particularly those who opposed slavery or harbored deep loyalty to the U.S. government (despite its past injustices), the Union offered a different kind of hope. Among the Creek Nation, a significant faction led by Opothleyahola remained fiercely loyal to the Union. They refused to sign treaties with the Confederacy and attempted to lead a mass exodus of pro-Union Native Americans—including Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees—north to Kansas for protection. This "Flight of the Loyal Creeks" became a harrowing journey, constantly pursued by Confederate and pro-Confederate Native American forces, resulting in battles like Round Mountain, Chusto-Talasah, and Shoal Creek. Many perished from exposure, starvation, or battle wounds.

The Cherokee Nation itself was fractured. While Stand Watie led the pro-Confederate faction, Chief John Ross and many of his followers, though initially neutral, eventually sided with the Union after Confederate troops occupied their capital, Tahlequah, and forced Ross to flee. The conflict within the Cherokee Nation became a bitter civil war within a civil war, pitting brother against brother, family against family, in a struggle that would haunt them for generations.

Union forces also actively recruited Native Americans, though often with less fanfare and fewer formal treaties than the Confederacy. Native American scouts and soldiers served in various capacities, particularly along the Western frontier and in the Indian Territory itself. Their knowledge of the terrain and their fighting skills were invaluable.

Perhaps the most famous Native American to serve the Union was Ely S. Parker, a Seneca sachem (chief) from New York. A trained engineer and lawyer, Parker served as General Ulysses S. Grant’s military secretary. He was a trusted advisor, a brilliant strategist, and a key figure in Grant’s inner circle. It was Parker who famously drafted the final surrender terms signed by Grant and Lee at Appomattox Court House, marking a symbolic moment of Native American presence at the war’s conclusion. Later, Parker would become the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs, serving from 1869 to 1871.

The Indian Territory: A War Zone of its Own

The Indian Territory became a brutal and overlooked theater of the war. It was marked by constant skirmishes, raids, and a devastating guerilla war that often involved Native American units fighting each other. The Battle of Honey Springs (July 17, 1863), the largest battle fought in the Indian Territory, saw Union forces (including African American and Native American regiments) decisively defeat a Confederate force that included significant numbers of Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw soldiers. This Union victory was a turning point, giving the North control over much of the territory and its vital supply routes.

The war in the Indian Territory was particularly destructive. Homes were burned, farms destroyed, and civilians displaced. The conflict exacerbated existing tribal divisions and created new ones, leading to years of internal strife and violence even after the main war ended.

Motivations and Legacy

The involvement of Native Americans in the Civil War was not about abstract ideologies like "states’ rights" or "union." For them, it was primarily a struggle for survival, self-preservation, and the protection of their remaining lands and sovereignty. Their choices were pragmatic, based on which side they believed would offer them the best chance for their nations to endure. As historian Mary Jane Warde wrote, "The Native American nations were not fighting for the Union or the Confederacy in the same way that white Americans were. They were fighting for their own nations, for their survival, and for the recognition of their treaty rights."

The irony was stark: Native Americans, whose own sovereignty and land rights had been systematically eroded by the U.S. federal government, were now fighting in a war ostensibly about states’ rights and the power of the federal government. No matter which side they chose, they were caught between two powerful forces, both of whom had historically demonstrated a disregard for Native American welfare.

The aftermath of the war was particularly harsh for the Native American nations. Despite their service, both Union and Confederate Native American tribes suffered. The U.S. government, claiming that the Confederate-allied tribes had forfeited their rights by siding with the rebellion, imposed new, punitive treaties. These treaties often resulted in further land cessions, the dissolution of tribal governments, and the opening of their lands to white settlement. Even the loyal tribes, like the Opothleyahola’s Creeks, did not escape unscathed, facing pressure to cede land for the resettlement of other tribes and for railroad expansion.

The Civil War left deep scars within Native American communities, exacerbating existing divisions and contributing to a period of instability and further loss. It shattered their hopes for true self-determination and accelerated the process of their eventual assimilation into American society.

Today, remembering the role of Native Americans in the Civil War is crucial for a more complete understanding of this pivotal period in American history. Their participation was not a footnote but a vital, complex, and often tragic chapter, demonstrating their enduring resilience, their strategic acumen, and the profound, multifaceted impact of the war on all who lived within the nascent American nation. Their story reminds us that the Civil War was truly a war on many fronts, with consequences that reverberated far beyond the battlefields of the East.