The Yamasee War: South Carolina’s Crucible of Blood and Betrayal

Good Friday, April 15, 1715. The air in the Yamasee town of Pocotaligo, nestled deep within the South Carolina Lowcountry, was thick with an uneasy tension, not the usual reverent calm of a holy day. A delegation of English traders and colonial officials, including Thomas Nairne, the colony’s Indian Agent, and John Wright, a prominent trader, had arrived, ostensibly to address growing grievances with the Yamasee people. They had spent the night in anxious discussions, sensing the palpable resentment simmering beneath the surface.

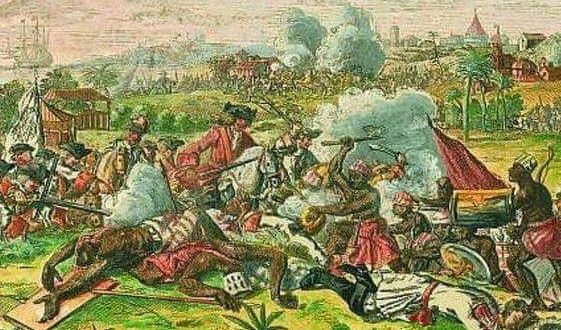

As dawn broke, the fragile peace shattered. Without warning, Yamasee warriors, who had seemingly offered hospitality, launched a brutal attack. Nairne was tortured and executed; Wright and others met a swift, violent end. This meticulously planned massacre was not an isolated act of vengeance but the deliberate, fiery spark that ignited the Yamasee War, a conflict that would push the fledgling colony of South Carolina to the very brink of annihilation and fundamentally reshape the future of the American South.

What was the Yamasee War? It was a two-year conflagration (1715-1717) between the English colonists of South Carolina and a confederation of Native American tribes, primarily the Yamasee, but quickly joined by the Creek, Choctaw, Catawba, Apalachee, and others. More than just a frontier skirmish, it was a desperate struggle for survival, born from decades of simmering resentments, economic exploitation, and a profound clash of cultures. Historians widely regard it as one of the most destructive and significant Native American wars in colonial American history, with an estimated 7% to 10% of the colony’s white population perishing in the fighting, a staggering toll.

The Powder Keg: A Century of Grievances

To understand the ferocity of the Yamasee War, one must delve into the decades preceding it, a period marked by rapid colonial expansion and the burgeoning, brutal economy of the Proprietary colony of Carolina. Settled in 1670, Carolina thrived on a triangular trade of deerskins, rice, and, most disturbingly, Native American slaves.

The Indian Slave Trade: A Viper in the Heart of Relations

Perhaps the single most explosive factor was the burgeoning Indian slave trade. Carolina’s Indian slave trade had exported an estimated 10,000 to 12,000 Native Americans to other colonies and the West Indies between 1670 and 1715. The Yamasee, themselves once victims of Spanish slave raids, had become crucial, if unwilling, partners in this grim enterprise. They had settled in southern Carolina after the Yamasee War of 1702–1709, seeking protection from the Spanish and their allied tribes in Florida. They were pressed into service by the Carolinians, forced to raid their traditional enemies and even their former allies to capture individuals for sale.

This system was inherently destabilizing. As historian Alan Gallay notes in The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717, "The demand for slaves led to a perpetual state of warfare among Indian groups, tearing apart traditional alliances and creating new enmities." The Yamasee, caught between the insatiable demands of the colonists and the growing animosity of their neighbors, found their position increasingly precarious. They feared that, once the supply of other tribal captives dwindled, they themselves would become the next targets of their English "allies."

Land Encroachment: The Relentless Creep Westward

Beyond the slave trade, the relentless westward expansion of English settlements was a constant source of friction. Planters, driven by the lucrative rice economy, pushed deeper into Native American territories, clearing forests, establishing farms, and disrupting traditional hunting grounds. Treaties were often ignored or misinterpreted, and land was taken with little regard for indigenous claims. The Yamasee, living in close proximity to the expanding settlements, felt this pressure acutely.

+The+Yamasee+(Creek)+Tribe+attacked+and+killed+South+Carolinian+traders+in+coastal+towns..jpg)

Trade Abuses: Whiskey and Wampum

Compounding these issues were rampant abuses within the deerskin trade. English traders, often operating with little oversight, frequently cheated Native Americans. They manipulated weights and measures, sold shoddy goods, and extended credit at exorbitant rates, trapping entire communities in inescapable cycles of debt. Alcohol, particularly rum, was used as a tool of exploitation, leading to social breakdown and further indebtedness. As the debts mounted, traders began to seize Native American land, goods, and even family members as collateral, fueling deep resentment and a sense of betrayal.

Disease and Cultural Erosion:

The arrival of Europeans also brought devastating epidemics of smallpox, measles, and other diseases against which Native Americans had no immunity. These waves of sickness decimated populations, further weakening communities and disrupting social structures. Coupled with the relentless pressure to adopt English customs, language, and religion, these factors contributed to a profound sense of cultural loss and a growing desperation.

By 1715, the Yamasee, along with other tribes like the Creek, Catawba, and Cherokee, had reached their breaking point. The abuses were too widespread, the threats too existential. They saw the English not as partners, but as an existential threat that must be confronted.

The Spark: Good Friday, 1715

The Yamasee, deeply concerned by their mounting debts and the perceived threat of enslavement, dispatched a delegation to Pocotaligo to confront the English traders. The exact details of the final negotiation remain murky, but it’s clear that the Yamasee had already decided to act. The massacre of Nairne and his party was a deliberate declaration of war, a calculated strike designed to send an unambiguous message.

"The war started with a horrifying suddenness," wrote Governor Charles Craven, who narrowly escaped the initial onslaught himself. The Yamasee warriors, numbering in the hundreds, immediately launched a coordinated assault on scattered English plantations and settlements in the Lowcountry. Families were murdered, homes burned, and the frontier descended into chaos.

A Colony on the Brink: The War’s Brutality and Spread

The Yamasee’s initial successes were devastating. They swept through the southern frontier, driving survivors towards Charles Town (modern-day Charleston). Within weeks, the conflict escalated, drawing in more tribes who had their own grievances against the colonists. The Catawba, formidable warriors from the Carolina Piedmont, joined the Yamasee, launching attacks on the northern frontier. The Creek, the most powerful confederacy in the Southeast, though initially hesitant, also entered the fray, their warriors raiding the western settlements.

Charles Town, the heart of the colony, became a besieged fortress. Refugees streamed in, bringing harrowing tales of massacres and destruction. The colony’s very existence hung by a thread. Governor Craven, a seasoned military man, took decisive action. He declared martial law, mustered every able-bodied white man into militias, and armed enslaved Africans, promising them freedom for their service (a promise largely unfulfilled).

The fighting was brutal. Both sides committed atrocities. Native American warriors, fueled by rage and a desire for retribution, spared few settlers. Colonial militias, in turn, adopted a scorched-earth policy, destroying Native American towns and crops. "It was a war of extermination," wrote a contemporary observer, "where mercy was rarely given or received."

Shifting Tides: Diplomacy and Betrayal

Despite the initial unity of the Native American confederation, internal divisions and British diplomacy began to turn the tide. The sheer power of the English, combined with their ability to supply goods and firearms, proved to be a powerful lever.

The Cherokee Alliance: A Critical Turning Point

The most crucial turning point came with the Cherokee. The largest and most powerful Native American nation in the Southern Appalachians, the Cherokee had initially been ambivalent, torn between their desire to curb English expansion and their traditional enmity with the Creek. Both the English and the Creek vied for their allegiance.

Governor Craven’s agents, particularly George Chicken, skillfully negotiated with the Cherokee, offering trade goods, firearms, and assurances of land. More importantly, they exploited the long-standing rivalry between the Cherokee and the Creek. The Cherokee feared that a victorious Creek-Yamasee alliance might become too powerful and threaten their own dominance in the region. In late 1715, the Cherokee launched a surprise attack on a Creek delegation at Tugaloo, killing their leaders and decisively siding with the Carolinians. This act of betrayal fundamentally altered the balance of power.

With the Cherokee’s entry, the tide began to turn. The Creek, disheartened and facing a two-front war, largely withdrew from the conflict. The Yamasee, their numbers dwindling, were steadily pushed back, first from their Lowcountry strongholds and then further south into Spanish Florida, where they sought refuge near St. Augustine.

By 1717, the major fighting had subsided. While sporadic raids continued for several years, the immediate threat to the colony was over.

The Aftermath: A Reshaped South

The Yamasee War left an indelible mark on the landscape of South Carolina and the broader American South.

Devastation for Carolina: The colony was ravaged. Half its townships were ruined, trade was disrupted, and its population significantly reduced. The war had cost South Carolina dearly in lives and resources, exposing the fatal flaws of the Proprietary government.

The End of the Indian Slave Trade: The war effectively brought an end to the large-scale Indian slave trade in Carolina. The devastation and instability it caused demonstrated its unsustainable nature. Consequently, the colony pivoted almost entirely to African chattel slavery to meet its labor demands, leading to a dramatic increase in the importation of enslaved Africans and solidifying the racialized caste system that would define the South for centuries.

Collapse of Proprietary Rule: The war exposed the inability of the Lords Proprietors to adequately protect their colony. Faced with ruin, the colonists appealed directly to the British Crown for protection and governance. In 1719, the Proprietary government was overthrown in a bloodless coup, and South Carolina became a Royal Colony in 1729, signaling a new era of direct British oversight and military protection. This shift brought more stability and resources, allowing the colony to rebuild and expand.

Redefining Anglo-Native Relations: The war forced a re-evaluation of Native American policy. Instead of relying on volatile trade relations and the slave trade, the Crown sought to establish more formal treaties and buffer zones. The Cherokee and Creek, though diminished, remained powerful forces, and the British realized the necessity of maintaining diplomatic ties and securing their allegiance against rival European powers (French and Spanish).

Reshaping Native American Communities: For the Native American tribes involved, the war was catastrophic. The Yamasee, decimated and displaced, never recovered their former power. Other groups, like the Catawba, consolidated their numbers for survival. The Creek Confederacy, though weakened, adapted and remained a significant power. The Cherokee, having sided with the British, solidified their position, albeit with the long-term consequence of increased reliance on colonial trade. The war accelerated the process of tribal consolidation and migration, fundamentally altering the demographic and political landscape of the Southeast.

A Pivotal, Yet Often Overlooked, Chapter

The Yamasee War, often overshadowed by later conflicts like the French and Indian War or the American Revolution, was a pivotal moment in American history. It demonstrated the lethal consequences of unchecked colonial ambition and economic exploitation. It marked the definitive shift from Native American to African chattel slavery in the South. It led directly to South Carolina becoming a Royal Colony, strengthening British imperial control. And it irrevocably altered the lives and futures of the Native American peoples caught in its devastating wake.

The echoes of that Good Friday massacre in Pocotaligo resonated for generations, shaping the complex, often violent, tapestry of the American South. It serves as a stark reminder that the colonial frontier was not merely a blank slate for European expansion, but a contested, vibrant, and ultimately tragic ground where cultures clashed, and the price of progress was often paid in blood.