The Long Shadow of Assimilation: Native American Boarding Schools and the Stolen Generations

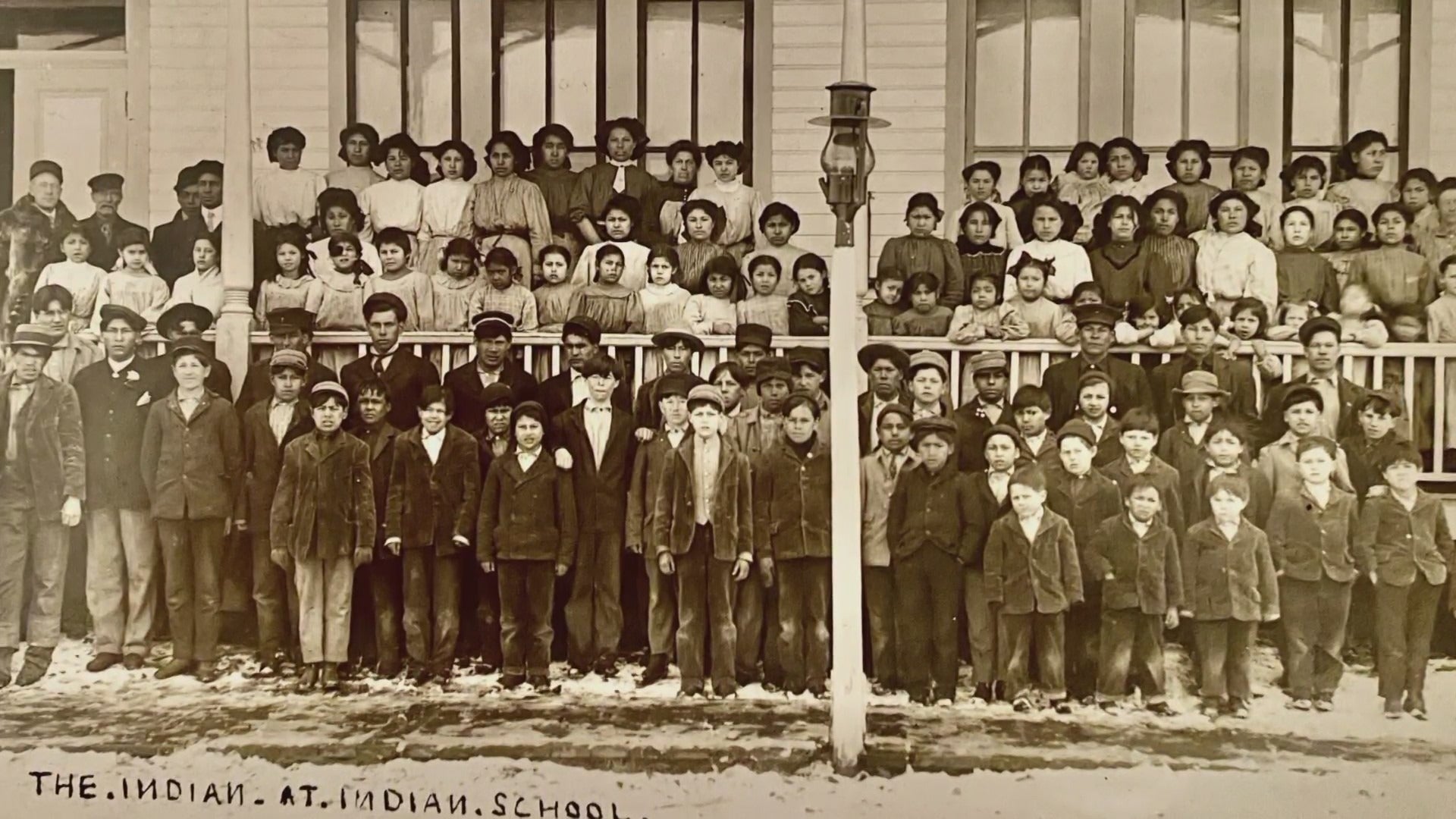

For over a century, from the mid-19th to the late 20th century, thousands of Native American children were systematically removed from their homes, families, and cultures and forced into a vast network of boarding schools across the United States. These institutions, operated by the federal government and various religious organizations, were not schools in the conventional sense. They were instruments of assimilation, designed with a singular, brutal purpose: to "kill the Indian and save the man."

This dark chapter in American history represents a deliberate and widespread attempt at cultural genocide, leaving an indelible scar on generations of Indigenous peoples. The legacy of these schools is a complex tapestry of profound loss, intergenerational trauma, resilience, and a growing demand for truth, healing, and justice.

The Genesis of a Policy: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man"

The origins of the Native American boarding school system can be traced to the post-Civil War era, a period marked by westward expansion and the U.S. government’s intensified efforts to control and "civilize" Indigenous populations. Traditional military campaigns against Native nations were proving costly and often unsuccessful. A new strategy emerged, one that targeted the very heart of Indigenous identity: their children.

The architect of this assimilationist policy was Captain Richard Henry Pratt, a former military officer who founded the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879. Pratt’s philosophy, encapsulated in his infamous maxim, "A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man," became the guiding principle for the entire system.

Pratt believed that by stripping Native children of their language, religion, clothing, and customs, they could be transformed into "productive" members of white American society. This vision was embraced by government officials and religious groups, who saw it as a humanitarian effort, a way to uplift and integrate Native peoples, albeit through forced conversion and cultural eradication. By 1900, there were over 150 boarding schools operating across the nation, many run by Catholic and Protestant denominations under federal contract.

Life Inside: A Regimen of Erasure and Abuse

For the children forcibly enrolled in these schools, life was a stark contrast to the warmth and communal life of their homes. Upon arrival, the process of "civilization" began immediately and brutally. Their long hair, a sacred symbol of identity and connection in many Native cultures, was cut short. Traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms. Their Indigenous names were often replaced with English ones, further severing their ties to their heritage. Speaking their Native languages was strictly forbidden, often enforced with severe corporal punishment.

"They took our names, they cut our hair, they made us forget who we were," recalled countless survivors, their testimonies painting a harrowing picture of daily life. The curriculum focused on vocational training for boys (agriculture, carpentry) and domestic skills for girls (sewing, cooking, cleaning), often exploiting their labor to maintain the schools themselves. Academic instruction was rudimentary, secondary to the goal of cultural re-education.

Discipline was harsh and pervasive. Children were subjected to physical, emotional, and, in many documented cases, sexual abuse by staff members. Beatings, solitary confinement, and public humiliation were common punishments for infractions as minor as speaking a Native language or expressing homesickness. The psychological toll was immense, fostering fear, shame, and a deep sense of alienation.

Conditions in many schools were squalid, leading to widespread disease. Tuberculosis, influenza, and other contagious illnesses swept through the dormitories, often with fatal consequences. Malnutrition was common, and medical care was often inadequate or nonexistent. Thousands of children died in these institutions, buried in unmarked graves far from their ancestral lands. The exact number remains unknown, a testament to the system’s callous disregard for Native lives.

The Deep Wounds of Intergenerational Trauma

The boarding school era formally began to decline in the mid-20th century, with significant reforms emerging in the 1930s and a gradual shift towards day schools on reservations. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978, which prioritized the placement of Native children with Native families, was a landmark step in addressing the historical trauma of forced removal. However, the last federal boarding school did not close until the 1990s.

The impact of this century-long policy is not confined to the past; it reverberates powerfully through Native American communities today. Survivors, often referred to as "stolen generations," carried the scars of their experiences throughout their lives. Many struggled with mental health issues, addiction, and difficulties forming healthy relationships due to the trauma they endured and the severing of family bonds.

Perhaps the most devastating legacy is intergenerational trauma. Children of survivors often grew up with parents who were emotionally distant, unable to express affection, or who struggled with anger and substance abuse – direct consequences of their own boarding school experiences. The forced loss of language and cultural practices meant that younger generations were often disconnected from their heritage, leading to a sense of identity confusion and a weakening of community ties.

"My parents never talked about it, but you could see it in their eyes, in their silence," shared a descendant of boarding school survivors. "It was like a wound that never healed, passed down through the family." The breakdown of traditional family structures and parenting practices, coupled with the erosion of spiritual beliefs, created deep societal challenges that Native nations are still working to overcome.

A Reckoning and the Path to Healing

In recent years, there has been a growing movement among Indigenous communities and allies to uncover the full truth of the boarding school era and initiate processes of healing and reconciliation. Inspired by similar efforts in Canada, where a Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigated residential schools, calls for accountability in the U.S. have intensified.

In 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary, launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. This comprehensive review aims to identify former boarding school sites, locate unmarked burial grounds, and compile historical records to shed light on the system’s full scope and impact. "The Department of the Interior will shed light on the truth of these institutions," Haaland stated, acknowledging her own family’s experience with boarding schools. "We must address the intergenerational trauma that continues to haunt our communities."

Preliminary findings from the initiative have confirmed the existence of over 500 boarding school sites and thousands of unmarked graves, with more expected to be uncovered. This investigation is a crucial step towards acknowledging the historical injustices and providing a factual basis for healing.

Beyond government initiatives, Native communities are leading their own efforts to reclaim languages, revitalize cultural practices, and provide support for survivors and their descendants. Oral histories are being collected, ceremonies of remembrance are being held, and educational programs are being developed to ensure that this painful history is never forgotten. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) is a prominent organization dedicated to advocating for survivors, documenting the history, and promoting healing.

The story of Native American boarding schools is not merely a chapter of the past; it is a living history that continues to shape the present. Understanding this history is essential for all Americans, not just for Indigenous peoples. It forces a confrontation with the uncomfortable truths of colonization and assimilation, highlighting the devastating consequences of policies that sought to erase an entire people’s identity.

As communities continue the arduous journey of healing and remembrance, the goal remains clear: to honor the children who never returned home, to support the survivors who endured unimaginable hardship, and to ensure that such a systematic assault on culture and humanity never happens again. The path to true reconciliation begins with truth, acknowledgment, and a commitment to justice for the stolen generations.