The Great American Enigma: Unraveling When the First Peoples Arrived

For centuries, the question of when and how the first humans arrived in the Americas has captivated scientists, historians, and Indigenous communities alike. It’s a mystery deeply embedded in the continent’s soil, etched in ancient bones, and whispered through generations of oral traditions. Far from a simple historical date, it is a profound inquiry into human resilience, migration, and the very origins of the diverse cultures that thrived long before European contact.

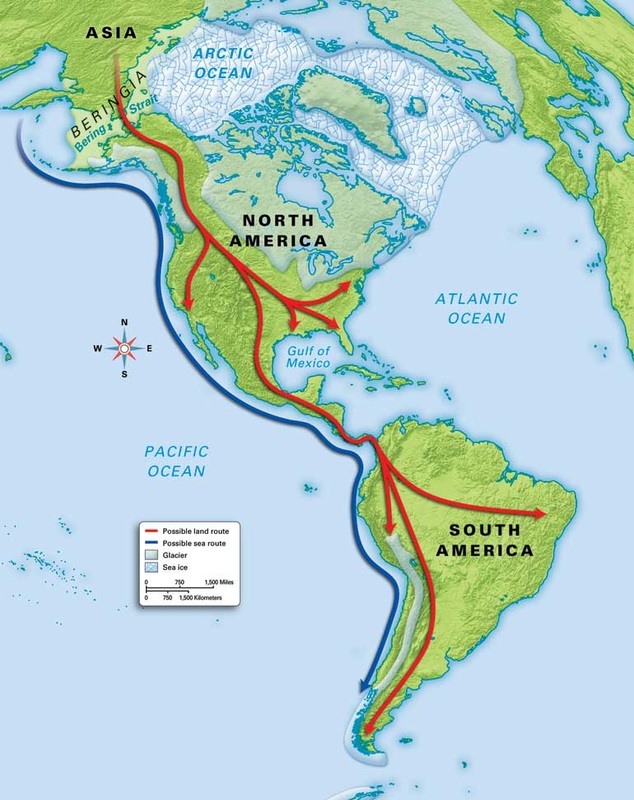

For much of the 20th century, a theory known as "Clovis First" dominated the scientific consensus. Named after distinctive fluted projectile points discovered near Clovis, New Mexico, this paradigm posited that the first Americans were big-game hunters who crossed a land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska – known as Beringia – around 13,500 to 13,000 years ago. These Clovis people, according to the theory, then rapidly spread across North and South America, their signature tools marking the earliest human presence. It was a neat, elegant model, easy to grasp, and supported by a growing body of archaeological finds. The idea was that as the last great ice sheets retreated, an "ice-free corridor" opened up through Canada, allowing these pioneering groups to trek southward.

However, science is a dynamic process, and no theory, no matter how elegant, remains unchallenged indefinitely. Over the past few decades, a growing tide of archaeological discoveries, coupled with advances in genetics and climate modeling, has systematically dismantled the "Clovis First" monopoly. The story of America’s first inhabitants is proving to be far more complex, much older, and arguably more fascinating than previously imagined.

Cracks in the Ice: The Pre-Clovis Revolution

The first major crack in the "Clovis First" edifice appeared far south of New Mexico, in the temperate rainforests of southern Chile. In the late 1970s, archaeologist Tom Dillehay began excavating a site called Monte Verde. What he unearthed there was nothing short of revolutionary: remarkably preserved wooden structures, tools, medicinal plants, and even a child’s footprint, all definitively dated to approximately 14,500 years ago. This was a full 1,500 years before the earliest Clovis sites.

"Monte Verde was a game-changer," Dillehay recounted in numerous interviews. "It provided irrefutable evidence of a human presence in the Americas before Clovis, forcing a fundamental rethinking of everything we thought we knew." The implications were enormous. If people were in southern Chile 14,500 years ago, they must have entered the continent much earlier, and likely by a different route than the ice-free corridor, which wasn’t fully open at that time.

Monte Verde wasn’t an isolated anomaly. As researchers became more open to the possibility of pre-Clovis occupation, other sites began to yield similar, albeit sometimes controversial, evidence.

- Meadowcroft Rockshelter, Pennsylvania: Excavated by James Adovasio, this site has yielded artifacts and charcoal layers suggesting human occupation as far back as 16,000 years ago, and possibly even earlier, though some of its earliest dates remain debated.

- Paisley Caves, Oregon: Here, paleontologist Dennis Jenkins discovered ancient human coprolites (fossilized feces) containing human DNA, alongside Clovis-era and pre-Clovis tools. Radiocarbon dating pushed the age of these findings back to around 14,300 years ago, further strengthening the pre-Clovis argument.

- Buttermilk Creek Complex (Gault Site), Texas: Extensive excavations at this site have revealed deeply stratified layers containing thousands of tools that predate Clovis by as much as 2,000 years, demonstrating a sophisticated pre-Clovis culture.

- White Sands National Park, New Mexico: Perhaps one of the most compelling recent discoveries came in 2021. Ancient human footprints preserved in gypsum sediments were dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. While the dating method (radiocarbon dating of seeds found in the same layers as the footprints) has been subject to scrutiny and further verification is ongoing, if confirmed, these footprints would push the timeline of human arrival back by several millennia, dramatically reshaping our understanding.

These "pre-Clovis" sites, scattered across North and South America, paint a picture of a continent populated by diverse groups long before the widely recognized Clovis culture emerged. They demonstrate that the peopling of the Americas was not a single, rapid event, but likely a more complex, drawn-out process.

New Routes: Beyond the Land Bridge

If the ice-free corridor wasn’t open early enough, how did these earlier populations reach the Americas? The most compelling alternative is the Coastal Migration Theory, often referred to as the "Kelp Highway" hypothesis. This theory suggests that the first Americans traveled along the Pacific coast of Beringia and down the coasts of North and South America in boats, following a rich marine environment.

The logic is compelling:

- Availability of Resources: The coastlines, even during glacial periods, would have been teeming with marine life – fish, shellfish, seals, sea birds, and kelp forests – providing a consistent and abundant food source. This "kelp highway" would have offered a navigable and resource-rich pathway.

- Ice-Free Passage: While the interior was locked under vast ice sheets, sections of the coastal margins would have become ice-free much earlier, creating habitable refugia and potential routes.

- Evidence of Maritime Skills: While direct archaeological evidence of ancient boats from this period is scarce (due to rising sea levels submerging ancient coastlines), the ability to reach islands off the coast of California (like the Channel Islands) by at least 13,000 years ago, and sites like Monte Verde in Chile, strongly implies advanced maritime capabilities.

This coastal route would have allowed for a much earlier and potentially faster dispersal than the interior land bridge route, explaining the early presence of humans in places like Chile.

The Genetic Story: Tracing Ancestral Threads

While archaeology provides tangible artifacts, genetics offers a complementary, powerful lens through which to view the past. By analyzing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), passed down exclusively through the maternal line, and Y-chromosome DNA, passed down through the paternal line, scientists can trace ancestral lineages and estimate divergence times – when different populations split from a common ancestor.

Genetic studies have overwhelmingly supported an East Asian origin for Native American populations. Key findings include:

- Siberian Ancestry: Genetic markers unique to Native Americans trace back to populations in Siberia, confirming the Beringian connection.

- Beringian Standstill: Genetic evidence suggests that the ancestors of Native Americans may have lived in isolation in Beringia for several thousands of years – a "Beringian Standstill" – before dispersing into the Americas. This period, perhaps lasting from around 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, would have allowed for unique genetic mutations to accumulate.

- Timing of Divergence: Based on mutation rates, geneticists estimate that the initial wave of migration into the Americas likely occurred between 25,000 and 15,000 years ago, with the most robust estimates clustering around 18,000 to 15,000 years ago. This aligns well with the pre-Clovis archaeological sites.

- Multiple Waves: While the primary genetic signature points to a single major founding population, some genetic evidence suggests at least two, and possibly three, distinct migratory waves, contributing to the incredible diversity of Indigenous peoples across the continents.

Combining archaeological and genetic data, the current scientific consensus leans towards a scenario where the first people entered the Americas at least 18,000 to 15,000 years ago, likely via a coastal route, with subsequent migrations and dispersals, including the Clovis people, who represent a later, highly successful expansion.

Indigenous Perspectives: A Deeper Connection

It is crucial to acknowledge that scientific theories about migration and timelines are only one part of the story. For many Native American peoples, their presence on the land is not a matter of migration from a distant continent but of creation in situ. Oral traditions, passed down through countless generations, speak of origins directly from the land, sky, or water of their ancestral territories.

As Dr. Daniel Wildcat (Yankton Sioux), a scholar of Indigenous knowledge, states, "For Indigenous peoples, the land is not merely a place of arrival, but a source of identity, spirituality, and continuous connection. Our stories of creation speak to a timeless bond with this land, a relationship far deeper than any scientific migration theory can capture."

These narratives, often dismissed by early anthropologists, are rich, complex, and hold profound meaning for Indigenous communities. They embody a spiritual and cultural connection to place that transcends Western notions of linear time and historical migration. While scientific theories seek to answer "when did they arrive?" Indigenous narratives often answer "where do we come from?" and "who are we in relation to this land?" These are not necessarily conflicting viewpoints but different ways of understanding humanity’s deep past and relationship with the earth.

The Unfolding Story: A Continuing Journey

The question of when Native Americans arrived is no longer a simple one with a single answer. It is a vibrant, ongoing area of research, with new discoveries constantly reshaping our understanding. The once-dominant "Clovis First" paradigm has given way to a more nuanced, older, and geographically diverse narrative.

Future research will continue to explore submerged ancient coastlines for evidence of early maritime activity, refine genetic models, and meticulously excavate new sites. The potential for even earlier discoveries remains high, particularly in under-researched regions of the Americas.

Ultimately, the story of the first peoples of the Americas is a testament to human adaptability, ingenuity, and perseverance. It reminds us that our understanding of the past is always evolving, a dynamic interplay between scientific inquiry, archaeological discovery, and the enduring wisdom embedded in Indigenous cultures. The great American enigma continues to unravel, revealing a history far richer and more ancient than we ever dared to imagine.