When Empires Collided: King William’s War and the Scars of Colonial North America

Before the American Revolution carved a new nation from a continent, and long before the French and Indian War became a household name, the forests and fledgling settlements of North America were already a crucible of imperial ambition and brutal conflict. In the closing decades of the 17th century, a lesser-known but profoundly impactful struggle, King William’s War (1688-1697), set the stage for generations of bloodshed and shaped the very identity of the nascent colonial societies. It was the North American theatre of the wider Nine Years’ War in Europe, a clash between the burgeoning English colonies and the vast, strategically positioned French New France, exacerbated by the complex, often tragic, involvement of various Indigenous nations.

At its heart, King William’s War was a struggle for dominance—economic, territorial, and ideological—between two European superpowers vying for global supremacy. In Europe, the war pitted the League of Augsburg, led by William III of England (who had recently ascended the throne in the Glorious Revolution, displacing the Catholic James II), against the expansionist ambitions of Louis XIV’s France. This dynastic and religious conflict inevitably spilled across the Atlantic, where the stakes were even higher for the colonists on the ground: not just political power, but survival.

The Contenders and Their Stakes

On one side stood the English colonies, a sprawling patchwork of settlements along the Atlantic seaboard, from the Puritan strongholds of New England to the Quaker haven of Pennsylvania and the plantation economies of the South. Their population was growing rapidly, pushing ever westward, and their economic interests lay in agriculture, trade, and fishing. Militarily, they were largely reliant on local militias, often ill-equipped and poorly coordinated, and the sporadic, sometimes reluctant, assistance of the Crown. Their primary Indigenous allies were the powerful Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca), who had their own long-standing rivalries with the French and their allied nations.

Opposite them was New France, a territory vast in its claims, stretching from the Gulf of St. Lawrence down the Mississippi River, but sparsely populated compared to the English colonies. Governed more centrally and militarily, with its key strongholds at Quebec and Montreal, New France’s economy revolved around the lucrative fur trade and fishing. Its strategic advantage lay in its network of forts and its deep, often paternalistic, alliances with various Indigenous groups, particularly the Wabanaki Confederacy (Abenaki, Penobscot, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy) in Acadia (modern-day Nova Scotia and parts of Maine), and various Algonquin nations further west. These Indigenous allies were not mere pawns; they were sovereign nations with their own grievances, seeking to defend their ancestral lands from English encroachment and maintain their cultural integrity against European pressures.

The Spark Ignites: From Europe to the Frontier

The immediate spark for the North American conflict was the Glorious Revolution itself. When William III became King of England in 1689, a formal declaration of war against France soon followed. News traveled slowly across the Atlantic, but when it arrived, it formalized a conflict that was already simmering. Frontier skirmishes, driven by land disputes, fur trade rivalries, and long-held animosities between Indigenous groups and settlers, quickly escalated into full-blown warfare.

The war’s character was defined by its brutality and its decentralized nature. Unlike European battlefields dominated by massed armies, King William’s War was a conflict of devastating raids, ambushes, and sieges on isolated outposts. The English colonies, particularly New England and New York, bore the brunt of these attacks.

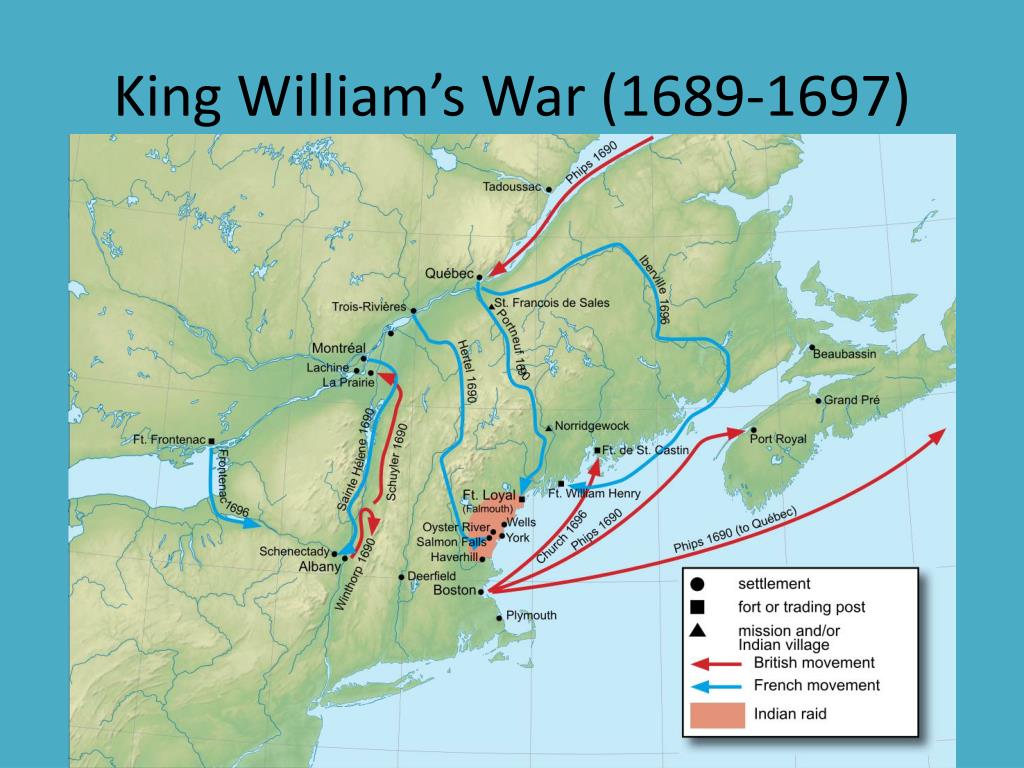

One of the most infamous episodes occurred on February 8, 1690, at Schenectady, New York. A mixed force of 210 French regulars, Canadian militiamen, and their Iroquois and Algonquin allies, under the command of Lieutenant Jacques Le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène, marched for weeks through deep snow. They launched a surprise predawn attack on the unsuspecting settlement. The ensuing massacre was horrific: more than 60 villagers, including women and children, were killed, many scalped, and some burned alive in their homes. Another 27 were taken captive. The settlement was utterly destroyed. "The cruelty of the enemy was such," wrote a contemporary account, "that they did not spare any age or sex, but butchered all that came in their way, with their Hatchets and Swords." This event sent shockwaves through the colonies, fueling fear and hardening resolve.

Similar atrocities were perpetrated throughout the war. Just weeks after Schenectady, a Franco-Indigenous force struck Salmon Falls, New Hampshire, killing 34 and taking 54 captives, burning the settlement to the ground. In Maine, settlements like York and Wells were repeatedly attacked, with homes razed and inhabitants killed or captured. These raids were not random acts of violence; they were a deliberate strategy by the French and their allies to terrorize the English frontier, disrupt their expansion, and secure their own territorial claims.

The English Response: Ambitious Failures and Limited Successes

The English colonies, despite their greater population, struggled to mount an effective counter-offensive. Their efforts were hampered by intercolonial rivalries, a lack of central authority, and logistical challenges. Nevertheless, they attempted several ambitious campaigns.

The most notable English military leader to emerge was Sir William Phips, a self-made man from Maine who had famously salvaged a sunken Spanish treasure ship. In 1690, Phips led a successful expedition against the French stronghold of Port Royal in Acadia. His forces easily captured the fort, and Phips declared Acadia annexed to the Crown. This victory, however, proved temporary.

Emboldened by this success, Phips immediately turned his attention to the grand prize: Quebec, the capital of New France, perched atop its formidable cliffs overlooking the St. Lawrence River. In October 1690, Phips, commanding a fleet of 32 ships and 2,300 militiamen, demanded the surrender of Quebec from its aging but defiant Governor General, Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac. Frontenac, who had returned to New France specifically to invigorate the war effort, famously retorted, "I have no reply to make to your general other than from the mouths of my cannons!"

Phips’s siege of Quebec was a dismal failure. Ill-prepared, lacking heavy artillery, and plagued by disease and poor coordination, his forces were repelled by Frontenac’s well-fortified defenses. The harsh Canadian winter was fast approaching, and after just a few days of ineffective bombardment and a failed land assault, Phips was forced to retreat, leaving behind cannons, supplies, and many dead and sick. The failure at Quebec was a massive blow to colonial morale and finances, plunging Massachusetts into significant debt.

Throughout the war, the Iroquois, while nominally allied with the English, found themselves increasingly caught in the middle. Their traditional enemies, the French and their Algonquin allies, continually raided their territories, and the English often failed to provide the promised support. The Iroquois suffered heavy losses, leading them to pursue their own diplomatic initiatives, often independent of their colonial partners.

The Human Cost and Enduring Scars

For the inhabitants of the frontier, King William’s War was a relentless nightmare. Settlements were abandoned, farms lay fallow, and the constant threat of attack created a pervasive atmosphere of fear. Hundreds of colonists were killed, and countless others were taken captive, often forced to endure brutal marches into enemy territory, where they might be adopted into Indigenous families, sold to the French, or held for ransom. These "captivity narratives" became a distinct literary genre in colonial America, detailing the horrors and resilience of those who endured them.

The economic toll was immense. Colonies like Massachusetts, which bore the brunt of the fighting, incurred crippling debts, financed by paper money that depreciated rapidly. Trade routes were disrupted, and the fishing fleets, a vital part of New England’s economy, were vulnerable to French privateers. The war diverted resources and manpower, hindering colonial development and exacerbating social tensions.

Beyond the immediate devastation, the war solidified a deep-seated animosity between the English and French, and between the colonists and their Indigenous adversaries. It also began to forge a distinct colonial identity. Faced with a common enemy and often feeling abandoned by the distant mother country, colonists started to see themselves less as mere subjects of the Crown and more as a unified, albeit still fragmented, people with shared experiences and challenges.

The Treaty of Ryswick and an Uneasy Peace

After nearly a decade of brutal fighting on both sides of the Atlantic, the European powers, exhausted and financially depleted, signed the Treaty of Ryswick in September 1697. In North America, the treaty essentially restored the status quo ante bellum, meaning that all territories conquered during the war were returned to their original owners. Port Royal, the only significant English gain, was handed back to France.

For the colonists who had endured years of terror, loss, and sacrifice, the treaty was deeply unsatisfying. It solved none of the fundamental issues that had ignited the conflict: the contested boundaries, the ongoing fur trade rivalries, or the underlying tensions between European powers and Indigenous nations. The Iroquois, who had fought valiantly, were not even directly included in the treaty negotiations, leading them to forge their own peace with New France in 1701, known as the Great Peace of Montreal.

King William’s War, therefore, was not an end but a prelude. It served as a brutal dress rehearsal for the even larger and more devastating conflicts that would follow: Queen Anne’s War (War of the Spanish Succession), King George’s War (War of the Austrian Succession), and ultimately, the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War), which would finally determine the fate of New France.

The scars of King William’s War ran deep. It established a pattern of frontier violence, inter-imperial rivalry, and complex Indigenous involvement that would define North American history for another century. It forced the colonists to confront their vulnerabilities, to adapt their defenses, and to begin to consider their collective future in a continent where European ambitions and Indigenous sovereignty were destined to clash repeatedly. Though often overshadowed by later conflicts, King William’s War was a foundational chapter in the violent, transformative saga of colonial North America, a period when empires collided, and the future of a continent hung precariously in the balance.