Echoes in the Dawnland: The Enduring Geography of the Abenaki People

To ask "Where did the Abenaki live?" is to embark on a journey across a landscape far older and more complex than the modern maps of states and nations. It is to trace the contours of a vibrant Indigenous civilization, the "People of the Dawnland," whose ancestral territories stretched from the Atlantic coast of what is now Maine, across the verdant valleys of New Hampshire and Vermont, and deep into the forested expanses of Quebec. Their homeland, known as Ndakinna (Our Land), was not merely a place of residence but the very crucible of their identity, culture, and survival.

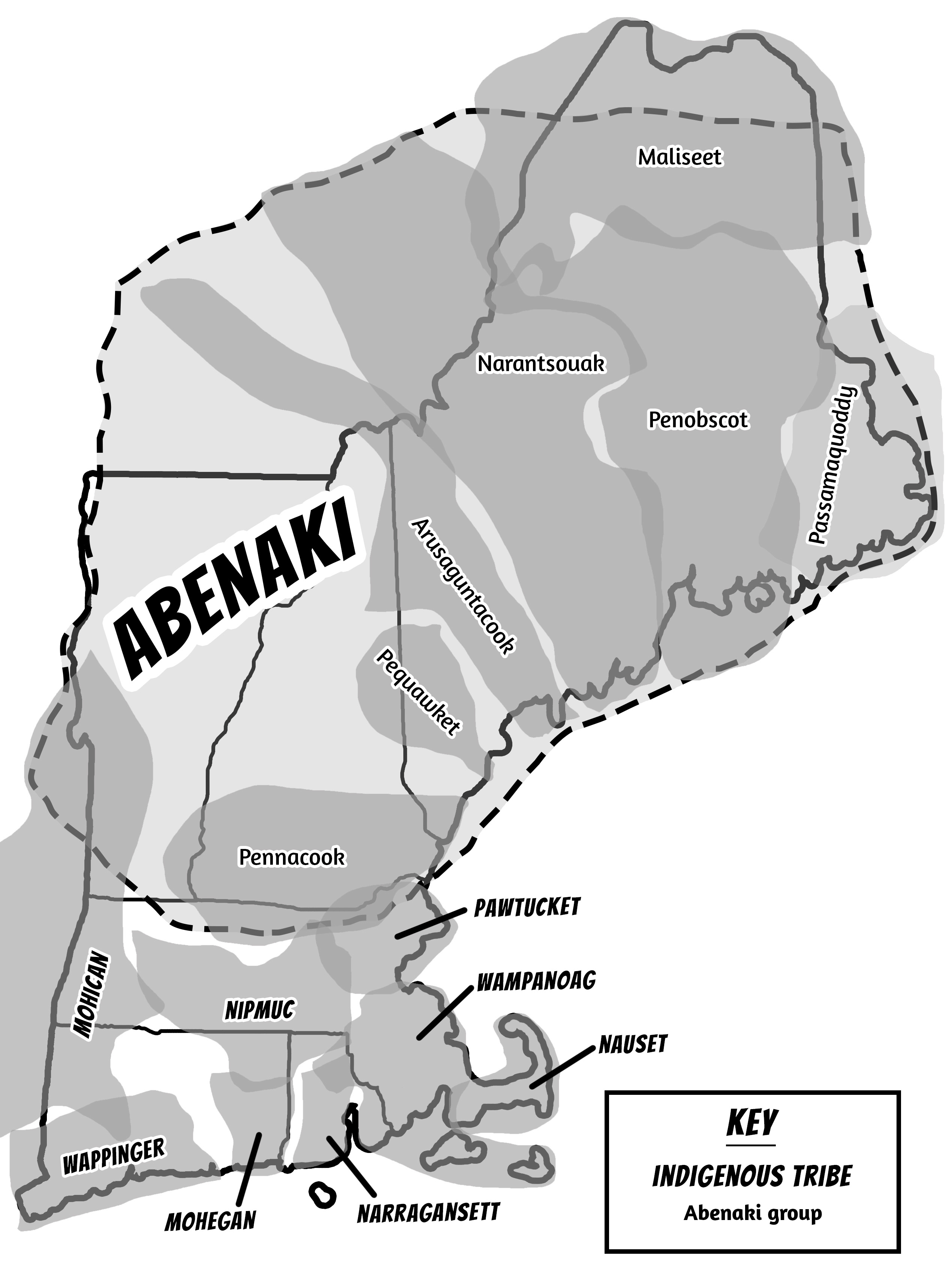

Before the arrival of European colonists, the Abenaki, a broad grouping of Algonquian-speaking peoples, were an integral part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, a powerful alliance that also included the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Mi’kmaq nations. This confederacy, whose name translates to "People of the Dawn," shared a common worldview and an interconnected territory spanning much of what is now New England and the Canadian Maritimes. Within this vast mosaic, the Abenaki occupied a central position, often serving as a bridge between the westernmost nations and those closer to the rising sun.

A Landscape of Life: Pre-Contact Ndakinna

The geographic heart of the Abenaki world was defined by its intricate network of rivers and lakes, which served as both highways and bountiful sources of sustenance. Their traditional territory encompassed the watersheds of major rivers like the Kennebec, Androscoggin, Saco, Merrimack, and crucially, the expansive Connecticut River, which flows south through Vermont and New Hampshire. To the north, their lands extended into the Quebec region, touching the shores of Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River valley.

Life in Ndakinna was characterized by a deep, reciprocal relationship with the natural world, dictated by the rhythm of the seasons. The Abenaki were semi-nomadic, moving strategically to access diverse resources. In the spring, they gathered along the major rivers to fish for salmon, shad, and alewives as they made their annual spawning runs. They cultivated fields of corn, beans, and squash in fertile river valleys, a practice that sustained them through the growing season. Summer saw them disperse into smaller family groups, journeying to the coast for shellfish, marine mammals, and berries, or moving to higher elevations for hunting and gathering.

As autumn approached, communities would return to their agricultural sites for harvest, then move deeper into the forests for the crucial fall hunting season, targeting moose, deer, bear, and beaver. Winter found them in smaller, more protected camps, often in sheltered valleys, relying on stored provisions and continued hunting. This seasonal mobility was not random; it was a sophisticated system of resource management, reflecting an intimate knowledge of the land’s ecological cycles. As Dr. Lisa Brooks, an Abenaki scholar, often emphasizes, "The rivers are our roads, and the mountains are our landmarks. Our stories are etched into this landscape." This deep connection meant that "where they lived" was not a static point on a map but a dynamic, interconnected web of places.

Divisions and Distinctions: Eastern and Western Abenaki

While united by language and culture, the Abenaki people were broadly categorized into two major groups based on their primary geographic orientation:

-

Eastern Abenaki: These groups predominantly inhabited what is now central and eastern Maine. Their territories included the vast watersheds of the Kennebec and Androscoggin Rivers, extending towards the Penobscot River (whose people, the Penobscot Nation, are closely related and often considered part of the broader Abenaki cultural sphere). Communities like the Norridgewock, Kennebec, and Androscoggin (Arosaguntacook) were prominent Eastern Abenaki bands, their lives intricately linked to the forest and coastal ecosystems of Maine. They were often the first to bear the brunt of early English colonization efforts, leading to significant displacement and conflict.

-

Western Abenaki: The Western Abenaki, including bands like the Sokoki, Cowasuck, Missisquoi, and Pennacook, occupied the lands of what is now Vermont, western New Hampshire, and parts of southwestern Quebec. Their primary artery was the Connecticut River, a vast waterway that connected them to other Algonquian-speaking peoples to the south. Lake Champlain, known to them as Bitawbagok ("The Waters Between"), was another vital component of their homeland, serving as a trade route and a source of abundant fish and game. The Green Mountains of Vermont and the White Mountains of New Hampshire also formed significant parts of their traditional hunting grounds.

This geographic distinction, however, was fluid. Intermarriage, trade, and shared cultural practices ensured continuous interaction between Eastern and Western bands. The mountains and rivers, rather than dividing them, often served as pathways for connection.

The Cataclysm of Contact and the Shifting Landscape

The arrival of European explorers, traders, and ultimately, settlers, brought cataclysmic changes to Ndakinna. The 17th and 18th centuries were marked by devastating epidemics that decimated Indigenous populations, followed by relentless warfare and land encroachment. The Abenaki, caught between the competing colonial ambitions of the French to the north and the English to the south, found themselves embroiled in a series of brutal conflicts, including King Philip’s War, Queen Anne’s War, and the French and Indian War.

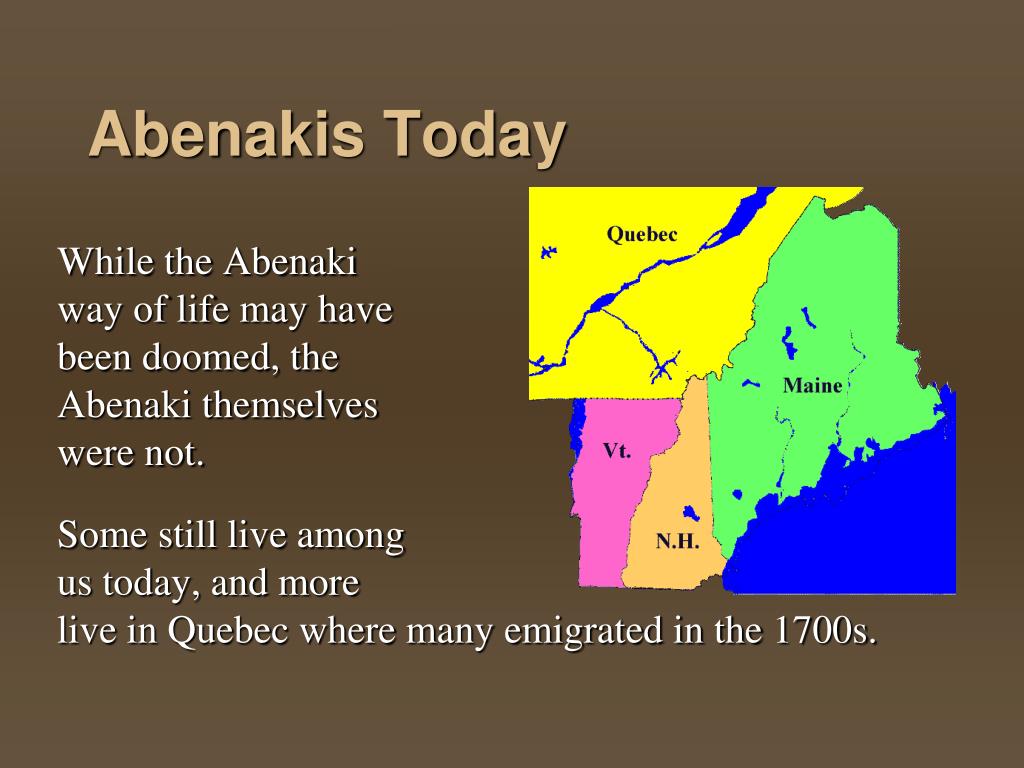

These conflicts, coupled with the insatiable demand for land by English colonists, forced many Abenaki to abandon their ancestral villages. Some sought refuge with French allies, migrating north into Quebec. This period saw the establishment of new, consolidated Abenaki communities like Odanak (St. Francis) and Wôlinak (Bécancour) along the St. Lawrence River. These settlements became vital centers of Abenaki cultural and linguistic preservation, even as they were far removed from much of their original homeland.

For those who remained in their ancestral territories, life became increasingly precarious. The imposition of colonial boundaries – the arbitrary lines drawn on maps by distant European powers – cut through traditional hunting grounds, disrupted seasonal movements, and fragmented communities. The creation of the U.S.-Canada border, for instance, divided families and made traditional cross-border travel for hunting, gathering, and ceremonial purposes illegal.

Despite treaties that often promised land protection (and were frequently violated), the Abenaki lost vast swathes of their territory through fraudulent sales, forced removals, and the simple weight of overwhelming colonial expansion. The narrative of "empty land" or terra nullius was a convenient fiction used to justify dispossession, ignoring millennia of Indigenous stewardship and occupation.

Resilience and Reassertion: The Abenaki Today

Even in the face of immense pressure and profound loss, the Abenaki people never truly left their land, nor did their connection to Ndakinna waver. While many were displaced, others remained in their ancestral territories, often living in hidden communities, maintaining their traditions in secret, or blending into the settler society to survive. This persistence is a testament to their deep cultural resilience.

Today, the Abenaki continue to assert their presence and rights across their traditional homeland. In Quebec, the Odanak First Nation and the Wôlinak First Nation are federally recognized, vibrant communities maintaining their language, ceremonies, and governance. They are active in land claims and cultural revitalization efforts, serving as important cultural anchors for Abenaki people everywhere.

In the United States, particularly in Vermont and New Hampshire, several Abenaki communities have achieved state recognition, including the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi, the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation, the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation, and the Elnu Abenaki Tribe. While federal recognition remains an ongoing struggle for many, these state recognitions are crucial steps in affirming their historical presence and current identity.

These contemporary communities are actively engaged in language revitalization, cultural education, and environmental stewardship, often working to restore and protect the very lands and waters that sustained their ancestors. They are involved in archaeological projects that uncover and affirm their long history in the region, and they educate the public about the true history of their homeland. For them, "Where did the Abenaki live?" is not a question about the past alone, but a living reality. Their traditional territories, though fragmented by modern borders and development, remain sacred.

Conclusion: The Enduring Heartbeat of Ndakinna

The question "Where did the Abenaki live?" invites a journey through time and across a vast, interconnected landscape. It reveals a sophisticated civilization deeply intertwined with its environment, whose existence was brutally disrupted but never extinguished. From the shimmering lakes of Champlain to the roaring rapids of the Kennebec, from the dense forests of the Green Mountains to the rocky coast of Maine, Ndakinna continues to echo with the stories, songs, and spirit of the Abenaki people.

Their resilience is a powerful reminder that land is more than property; it is identity, history, and future. The Abenaki, the People of the Dawnland, live not just in memory but in the ongoing reassertion of their sovereignty, culture, and profound connection to the heart of their ancestral home. Their presence ensures that the heartbeat of Ndakinna continues to resonate across the very lands where their ancestors walked for millennia.