Echoes of the River: Tracing the Enduring Ancestral Lands of the Arikara Nation

The story of the Arikara Nation, or Sahnish as they call themselves, is inextricably woven into the fabric of the North American plains, a narrative deeply rooted in the fertile river valleys and expansive grasslands that stretched across what is now the central United States. To ask "Where did the Arikara live?" is to embark on a journey through millennia of migration, adaptation, prosperity, and profound challenge, ultimately revealing a people whose connection to their ancestral lands transcends mere geography, embodying a spiritual and cultural bond that endures to this day.

For centuries, the Arikara were a prominent, semi-sedentary agricultural people whose heartland was the Missouri River, a vast, serpentine waterway that served as their economic highway, spiritual lifeline, and defensive barrier. Their presence was most concentrated in what is now North and South Dakota, though their influence and movements extended far beyond these modern state lines.

The Earliest Footprints: A Southern Genesis

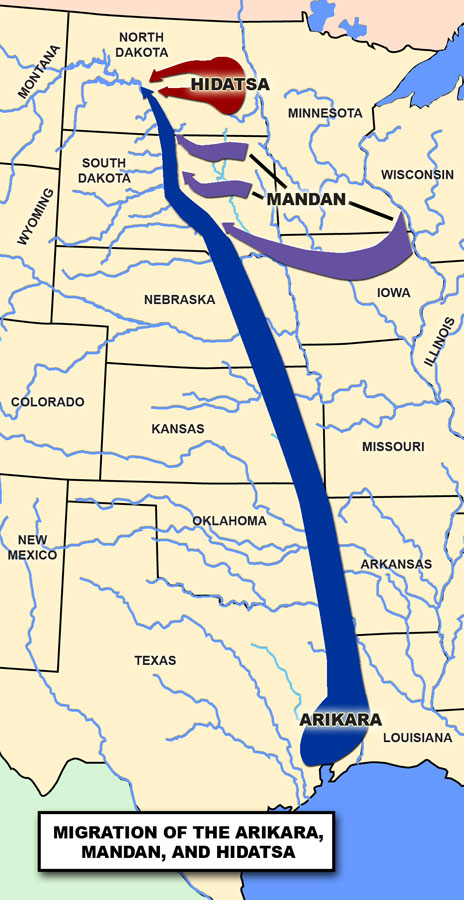

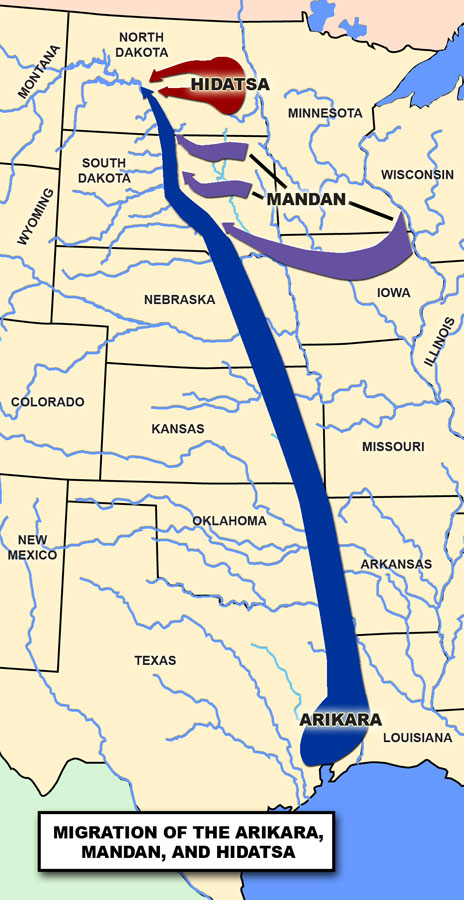

While their later history firmly places them along the Upper Missouri, the Arikara’s earliest origins, as evidenced by linguistic and archaeological studies, point to a more southern genesis. They are part of the Caddoan language family, a linguistic group that includes the Pawnee, Wichita, and Caddo peoples, primarily located in the Southern Plains. It is believed that the Arikara, then a northern branch of the Pawnee, migrated northwards, a gradual separation that likely occurred over centuries, driven perhaps by population pressures, environmental shifts, or the pursuit of new hunting and agricultural grounds.

Archaeological sites in present-day Nebraska and northern Kansas, dating back to the 14th and 15th centuries, bear witness to early Arikara settlements. These villages, often situated on high bluffs overlooking rivers like the Loup and Platte, already showcased the hallmarks of their future existence: large, circular earth lodges, extensive agricultural fields, and evidence of a sophisticated social structure. This initial phase established their identity as masterful cultivators of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers – crops that would remain central to their sustenance and culture throughout their history.

The Golden Age: Thriving on the Upper Missouri

By the 16th and 17th centuries, the Arikara had firmly established themselves along the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota, gradually moving further north into North Dakota. This period marked their zenith, a time when their villages dotted the riverbanks, becoming bustling centers of trade, agriculture, and complex social life. Sites like the Sully Village in South Dakota, which housed an estimated 6,000-8,000 people across hundreds of earth lodges, attest to the scale and sophistication of their settlements.

"Our villages were like living cities, breathing with the rhythm of the river and the seasons," recounted one Arikara elder, echoing ancestral memories. "Each earth lodge was a universe, a family’s heart, built from the very earth beneath our feet, solid and warm against the winter winds." These earth lodges, often 30 to 60 feet in diameter, were marvels of engineering: sturdy wooden frames covered with thick layers of sod, providing excellent insulation year-round. They were typically arranged around a central plaza, often with a ceremonial lodge and defensive palisades.

The Missouri River was more than just a place; it was a lifeforce. It provided fertile soil for their extensive gardens, a reliable source of water, and a transportation route for their distinctive bull boats. While primarily agriculturalists, the Arikara also engaged in seasonal buffalo hunts, venturing onto the plains to supplement their diet and acquire hides for clothing and lodge coverings. This blend of settled agriculture and nomadic hunting allowed them to thrive in the challenging Plains environment.

Their strategic location along the Missouri made them crucial intermediaries in the vast intertribal trade networks that crisscrossed the continent. They traded their surplus agricultural products, particularly corn, with nomadic tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Crow, who in turn offered buffalo meat, hides, and other plains resources. They also facilitated the exchange of goods from European traders, acquiring guns, metal tools, and glass beads, which they then traded further inland. This economic prowess fostered a period of relative stability and prosperity.

The Winds of Change: Disease, Conflict, and Displacement

The late 18th and early 19th centuries brought catastrophic changes that irrevocably altered the Arikara’s landscape and existence. The arrival of European and American traders and explorers, while initially bringing new trade goods, also introduced devastating epidemic diseases against which the Arikara had no immunity. Smallpox, cholera, and measles swept through their villages, often wiping out entire communities.

The smallpox epidemic of 1780-81 was particularly devastating, reducing their population from an estimated 30,000 to perhaps 10,000. The epidemic of 1837-38 was equally brutal, further decimating their numbers. These demographic collapses shattered their social structures, weakened their defenses, and made them more vulnerable to external pressures.

Simultaneously, the Arikara faced increasing pressure from expanding and well-armed nomadic tribes, particularly the Lakota (Sioux), who were also being pushed westward by Euro-American expansion. These conflicts, often over hunting grounds and trade dominance, led to a period of constant warfare, forcing the Arikara to consolidate their remaining people into fewer, larger, and more heavily fortified villages. They often sought refuge further north, closer to their allies, the Mandan and Hidatsa.

The Arikara War of 1823, a brief but significant conflict with the United States Army and fur traders, marked a turning point in their relationship with the burgeoning American nation. Though the Arikara achieved a tactical victory, preventing the Americans from establishing a permanent trading post in their territory, the event solidified a perception of them as hostile and contributed to their eventual marginalization.

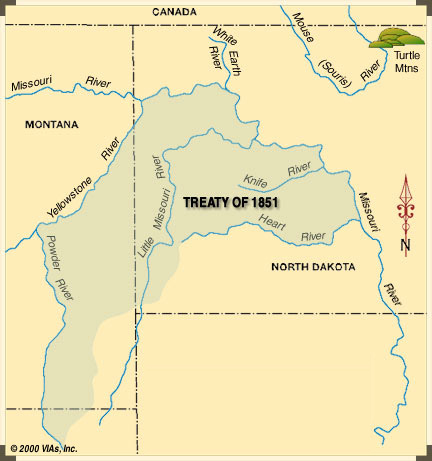

By the mid-19th century, their traditional territory had shrunk dramatically. Their once numerous villages were reduced to a handful, often located in close proximity to those of the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Knife River and later the Fort Berthold area.

A New Alliance: The Three Affiliated Tribes

Facing existential threats from disease, warfare, and land encroachment, the remaining Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa peoples made a pragmatic and powerful decision: they formally allied, forming what is now known as the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, or MHA Nation). This alliance, born out of shared adversity and a long history of intertribal relations, allowed them to pool their resources, share defensive strategies, and maintain a semblance of their cultural integrity amidst the encroaching tide of American settlement.

In 1870, the Fort Berthold Reservation was officially established for the Three Affiliated Tribes, encompassing a land base along the Missouri River in western North Dakota. This was a drastic reduction from their vast ancestral territories, but it provided a legal framework for their continued existence as a sovereign nation. Within this reservation, the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa continued their agricultural practices and adapted to the changing economic and social landscape, including the introduction of ranching and, eventually, wage labor.

The Garrison Dam: A Submerged Heartland

The 20th century brought another profound blow to the Arikara and their sister tribes. In the 1940s and 1950s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River, creating Lake Sakakawea, one of the largest man-made lakes in the world. While presented as a project for flood control and hydroelectric power, its construction submerged 156,000 acres of the Fort Berthold Reservation – approximately 25% of their remaining land base.

This was not just land; it was their most fertile agricultural bottomlands, their sacred sites, their ancestral burial grounds, and the locations of their last traditional villages. Thousands of people were forcibly relocated, their homes and livelihoods destroyed. "When the water rose, it didn’t just cover our fields, it covered our memories, our songs, our very identity," an Arikara elder lamented, remembering the devastating impact of the dam. "It was like a second death for our people, after the smallpox." The trauma of this forced displacement and the loss of their physical and spiritual heartland continues to resonate deeply within the MHA Nation.

The Enduring Connection: Sovereignty and Renewal

Today, the Arikara Nation, as part of the Three Affiliated Tribes, continues to reside on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. While their ancestral lands have been drastically reduced and altered, their connection to the land remains unbroken. The Missouri River, even in its dammed and altered state, is still central to their identity.

The MHA Nation is a vibrant, self-governing entity, working tirelessly to preserve and revitalize their unique language, traditions, and ceremonies. They have leveraged natural resources, particularly oil and gas reserves found on their lands, to build economic self-sufficiency and invest in their communities, establishing schools, health clinics, and cultural centers.

The question "Where did the Arikara live?" is no longer solely about historical geography; it is about the enduring spirit of a people. From their ancient southern roots to their established dominance along the Upper Missouri, through periods of immense hardship and displacement, the Arikara have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Their story is a testament to the profound and unbreakable bond between a people and their land – a bond that, despite all challenges, continues to define the Sahnish Nation, whose echoes still resonate along the sacred bends of the Missouri River. Their journey reminds us that land is not merely territory; it is identity, history, and the very soul of a people.