Echoes of the Plains: The Enduring Homeland of the Blackfoot Confederacy

The wind whips across the vast stretches of the North American plains, carrying with it the whispers of countless generations. For the Blackfoot Confederacy – a powerful alliance of four distinct but related nations – this immense landscape, stretching from the towering Rocky Mountains eastward across the prairies, was not merely a place to live; it was the very fabric of their identity, the source of their sustenance, and the stage for their vibrant history. To ask "Where did the Blackfoot Confederacy live?" is to embark on a journey through time, across an expansive geography, and into the heart of a resilient people whose connection to their traditional lands remains as profound today as it was centuries ago.

The Vast Canvas of the Pre-Contact Era

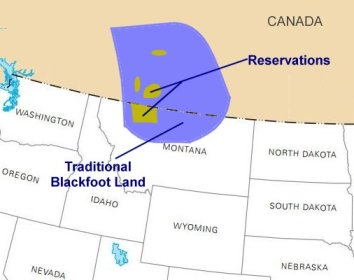

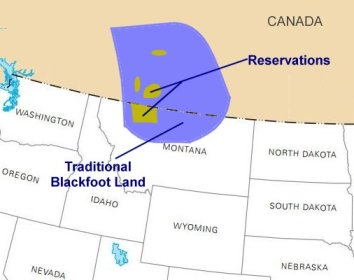

Before the arrival of European explorers and settlers, the traditional territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy was breathtaking in its scope. Comprising the Siksika (Blackfoot proper), Kainai (Blood), Aamsskáápí Pikuni (South Piikani, or Blackfeet Nation in the U.S.), and the Pikuni (North Piikani in Canada), their homeland was a sprawling heartland of the buffalo plains.

Their domain extended from the North Saskatchewan River in present-day Alberta, Canada, southward deep into what is now Montana, USA. To the west, their hunting grounds reached the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, which they revered as the "backbone of the world" – a sacred boundary offering shelter, timber, and diverse game. To the east, their territory stretched across the flat, rich grasslands of the prairies, encompassing significant portions of modern-day Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada, and Montana in the United States.

This vast landscape was no accident. It was strategically chosen and maintained through generations of profound ecological knowledge and, when necessary, fierce defense. The undulating plains, crisscrossed by rivers like the Bow, Belly, Oldman, and Marias, provided the perfect habitat for the American bison, or buffalo – the cornerstone of Blackfoot life. The buffalo provided everything: food, clothing, shelter (tipi covers), tools, and spiritual sustenance. The Blackfoot were masters of buffalo hunting, employing sophisticated techniques like the piskun (buffalo jump) long before the introduction of the horse.

Their semi-nomadic lifestyle was perfectly adapted to this environment. Following the great buffalo herds, they moved with the seasons, setting up temporary camps, conducting ceremonies, and engaging in trade with neighbouring tribes. This pre-contact era was characterized by a deep, reciprocal relationship with the land, where every feature – rivers, hills, even individual rocks – held stories, spiritual significance, and practical utility.

The Horse Revolution and Shifting Frontiers

The arrival of the horse, likely in the early 18th century, profoundly transformed Blackfoot life and further solidified their territorial dominance. Horses were not indigenous to North America, but their spread from the Spanish colonies in the south revolutionized hunting, travel, and warfare across the plains.

For the Blackfoot, horses meant greater mobility and efficiency in hunting buffalo, allowing them to pursue herds over wider distances and achieve greater success. This increased prosperity also led to a more centralized social structure and enhanced military prowess. With horses, the Blackfoot Confederacy became formidable warriors, capable of defending their vast territory against encroaching tribes like the Crow, Flathead, Kootenay, and Shoshone. Their hunting grounds and influence expanded, pushing the boundaries of their traditional territory and asserting their claim over prime buffalo ranges. This period, often called the "Golden Age" of the Plains Indians, saw the Blackfoot Confederacy at the zenith of its power and territorial control.

The Onslaught of Disease and the Fur Trade

However, this golden age was tragically short-lived. The very interactions that brought horses also brought devastating diseases. European traders, seeking furs, began to penetrate Blackfoot territory in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. While initially bringing new goods and opportunities for trade, they also inadvertently introduced diseases to which Indigenous populations had no immunity.

Smallpox epidemics were particularly catastrophic. The epidemic of 1780-82, carried up the Missouri River, decimated an estimated two-thirds of the Blackfoot population. Another severe outbreak in 1837, originating from an American Fur Company steamboat, reduced their numbers by more than half, from an estimated 15,000 to around 6,000. These epidemics ripped through communities, shattering social structures, weakening military strength, and creating immense psychological trauma. The land, once teeming with their people, now bore witness to immense loss. This weakening of their population made them increasingly vulnerable to the pressures that would soon come from westward expansion.

The Vanishing Buffalo and the Treaty Era

By the mid-19th century, the Blackfoot Confederacy faced an existential crisis. The insatiable demand for buffalo hides in the East, coupled with the relentless expansion of settlers, railways, and sport hunters, led to the catastrophic decimation of the buffalo herds. From tens of millions, their numbers plummeted to mere hundreds within a few decades. For a people whose entire way of life revolved around the buffalo, this was an unfathomable disaster. Starvation became widespread.

This ecological collapse, combined with increasing pressure from the burgeoning Canadian and American governments, forced the Blackfoot into a series of momentous decisions regarding their land.

In Canada, the Blackfoot Confederacy nations (Siksika, Kainai, and North Piikani) signed Treaty 7 with the Crown on September 22, 1877, at Blackfoot Crossing. Under this treaty, they ceded vast portions of their traditional territory in exchange for specific reserve lands, annual payments, and promises of assistance with farming and education. The reserves established under Treaty 7 were significantly smaller than their traditional lands but were intended to be permanent homelands. These include:

- Siksika Nation Reserve: Located east of Calgary, Alberta, along the Bow River.

- Kainai Nation (Blood Tribe) Reserve: The largest reserve in Canada by area, located southwest of Lethbridge, Alberta, near the Belly and St. Mary Rivers.

- Piikani Nation Reserve: Located southwest of Fort Macleod, Alberta, along the Oldman River.

South of the newly drawn international border, the Aamsskáápí Pikuni (Blackfeet Nation) experienced a similar, though distinct, process with the United States government. Through a series of treaties and agreements in the mid-to-late 19th century, including the Lame Bull Treaty of 1855, their vast territory was gradually reduced. Today, the Blackfeet Nation Reservation is located in northwestern Montana, bordering Glacier National Park. While still substantial, it represents a fraction of their original lands, extending from the Rocky Mountain Front eastward onto the plains, and is centered around the town of Browning, Montana.

The imposition of an international border, a European construct, artificially divided the Blackfoot people, making movement and communication between the northern and southern bands more challenging. Despite this, the shared language, culture, and kinship ties remained strong across the political divide.

Life on Reserves and Reservations: A New Reality

The transition to life on reserves and reservations was profoundly difficult. The nomadic lifestyle was replaced by forced sedentary living. Traditional hunting practices were outlawed, and the Blackfoot were encouraged, often coerced, into farming in a climate not always conducive to agriculture. Assimilation policies, including the devastating residential school system in Canada and boarding schools in the U.S., aimed to eradicate their language, culture, and spiritual beliefs.

The reserves became places of immense hardship, poverty, and cultural suppression. Yet, through it all, the Blackfoot people demonstrated remarkable resilience. They kept their languages alive, practiced ceremonies in secret, and held onto their deep spiritual connection to the land, even the reduced portions they were confined to.

The Enduring Homeland: Modern Blackfoot Nations

Today, the Blackfoot Confederacy continues to thrive, albeit within the boundaries of their modern land bases. While the vast traditional territory has been irrevocably altered by colonial settlement, the spirit of that land remains central to their identity.

- In Canada: The Siksika Nation, Kainai Nation (Blood Tribe), and Piikani Nation are vibrant, self-governing First Nations. They manage their reserve lands, pursue economic development initiatives (including agriculture, oil and gas, and tourism), and lead significant cultural revitalization efforts. Their reserves, though smaller than their historic territory, are still significant land bases, providing homes, livelihoods, and a foundation for cultural continuity. The Kainai Nation, for example, boasts the largest reserve in Canada by area, a testament to their enduring presence.

- In the United States: The Blackfeet Nation (Aamsskáápí Pikuni) is the largest Indian reservation in Montana and the fourth-largest in the U.S. They actively engage in economic development, natural resource management, and cultural preservation, including the revival of their language, traditions, and ceremonies. The proximity of the Blackfeet Reservation to Glacier National Park also highlights their historical connection to the mountain regions.

These modern nations are not merely confined to their current land; they continue to assert their aboriginal rights and title over their broader traditional territories, engaging in land claims, resource management discussions, and environmental stewardship across the landscape their ancestors once roamed freely. The rivers, the mountains, the sacred sites within their ancestral lands – even those outside their current reserve boundaries – continue to hold immense spiritual and cultural significance.

The question "Where did the Blackfoot Confederacy live?" is therefore answered with both a sweeping historical arc and a contemporary reality. They lived, and continue to live, across a magnificent stretch of the North American plains, a territory carved by glaciers and buffalo, shaped by their own ingenuity and resilience, and profoundly marked by the tides of history. Their current reserves and reservation are not just parcels of land; they are living testaments to an enduring connection to their ancestral homeland, a bond that transcends treaties, borders, and the passage of time. The echoes of the plains continue to resonate, carrying the stories of the Blackfoot people, forever intertwined with the land they call home.