The Enduring Homeland: Tracing the Footprints of the Catawba Nation

In the verdant heart of the Carolina Piedmont, where the winding Catawba River carves its path through ancient lands, lies the enduring homeland of the Catawba Nation. Their story is not merely one of geographic habitation but a profound testament to resilience, adaptation, and an unwavering connection to a territory they have called home for millennia. While maps might pinpoint their current reservation near Rock Hill, South Carolina, the true "where" of the Catawba stretches far beyond modern boundaries, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, culture, and survival woven into the very fabric of the Southeastern United States.

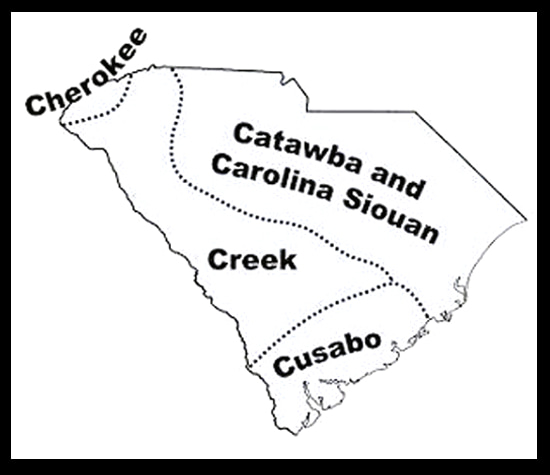

For countless generations, long before the arrival of European explorers, the ancestors of the Catawba flourished along the river that would eventually bear their name. This crucial waterway, known to them as Iswa (meaning "people of the river"), served as the lifeblood of their society, providing sustenance, transportation, and a spiritual connection to the land. Their ancestral territory spanned a significant portion of what is now the border region between North and South Carolina, extending roughly from present-day Charlotte, North Carolina, southward into central South Carolina, and encompassing the fertile lands along the Catawba, Wateree, and Congaree rivers.

A People of the River: Pre-Contact Flourishing

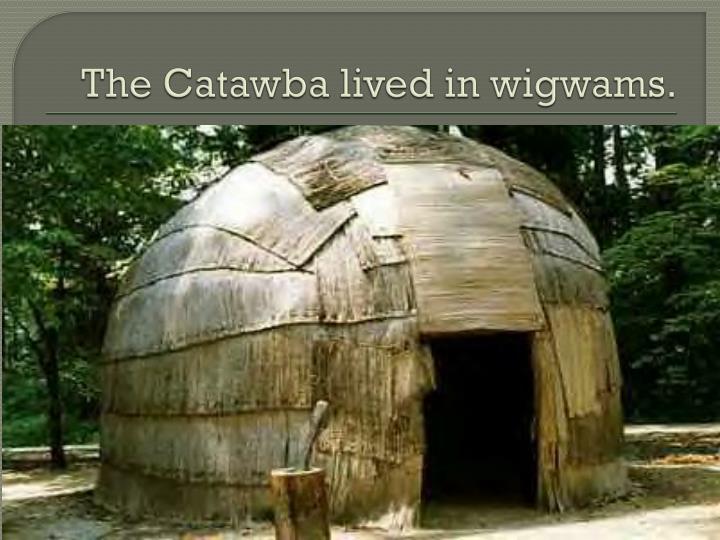

Archaeological evidence indicates a continuous human presence in the Catawba’s ancestral lands for at least 6,000 years, with the emergence of distinct Catawba cultural traits traceable back nearly a millennium. They were a settled, agricultural people, cultivating vast fields of corn, beans, and squash, complemented by hunting deer, bear, and smaller game, and fishing the abundant rivers. Their villages, often palisaded for defense, were centers of vibrant community life, characterized by sophisticated pottery, basketry, and intricate social structures.

The Catawba belonged to the Siouan language family, a linguistic group that once dominated much of the Piedmont region, distinguishing them from their Iroquoian-speaking neighbors to the north (like the Cherokee) and Muskogean-speaking peoples to the south. This shared linguistic heritage hints at broader cultural connections across the Piedmont before the fragmentation and consolidation that came with European contact.

"Our ancestors were tied to this land in every way imaginable," explains a modern Catawba elder, reflecting on their deep roots. "The river was our highway, our grocery store, our sacred place. You cannot separate us from this land, because it is who we are."

The Crucible of Contact: Disease, Diplomacy, and Consolidation

The arrival of Europeans in the 16th century marked a dramatic turning point. While Hernando de Soto’s expedition passed through the region in 1540, it was the subsequent waves of English and French traders and colonists that truly reshaped the Catawba’s world. With the Europeans came devastating diseases – smallpox, measles, influenza – against which Native populations had no immunity. Epidemics swept through communities, decimating populations and leading to the collapse of many smaller tribes.

The Catawba, though significantly impacted, demonstrated remarkable resilience. They became a beacon of stability in a tumultuous region, absorbing the remnants of other Siouan-speaking groups displaced and weakened by disease and conflict. Tribes like the Sugaree, Wateree, Waxhaw, and Cheraw, their numbers dwindling, sought refuge and merged with the Catawba. This consolidation, a grim testament to the devastating impact of European diseases, paradoxically became a cornerstone of Catawba strength, allowing them to maintain a significant population and a coherent political identity amidst regional chaos. By the early 18th century, the Catawba Nation was recognized by colonists as one of the most powerful and influential Native groups in the Carolinas, often referred to as "the Catawba Nation" even by colonial officials.

Strategic Allies in a Shifting Landscape

The 18th century saw the Catawba Nation strategically positioned at the crossroads of colonial expansion. Their territory, situated between the English settlements of South Carolina and the Cherokee lands to the west, made them indispensable, albeit often precarious, allies to the English. They participated in various colonial conflicts, including the Yamasee War (1715-1717) and the French and Indian War (1754-1763), often serving as scouts and warriors alongside colonial militias.

This alliance, however, came at a steep price. As colonial populations swelled, so did the pressure for land. Settlers encroached relentlessly on Catawba hunting grounds and ancestral lands, often disregarding treaties and agreements. Trade, while providing access to European goods like guns, tools, and textiles, also introduced alcohol and dependence, further disrupting traditional ways of life.

The Shrinking Homeland: Treaties and Betrayal

The pivotal moment in defining the Catawba’s "where" in the colonial era came with the Treaty of Augusta in 1763. In an attempt to stem the tide of settler encroachment and secure a formal land base for the tribe, the Catawba Nation ceded much of their vast ancestral territory to the British Crown. In return, they were granted a specific tract of land, fifteen miles square (approximately 144,000 acres), designated as their permanent reservation. This land, located along the Catawba River, became the legal and symbolic heart of the Catawba Nation.

However, even this legally established boundary proved difficult to maintain. The revolutionary fervor and subsequent establishment of the United States did little to alleviate the pressure. South Carolina, now an independent state, disregarded the 1763 treaty, claiming the land and allowing settlers to lease portions of the reservation. The Catawba, their numbers further reduced by disease and warfare, and facing increasing poverty, found themselves in a desperate situation.

The 1840 Treaty of Nation Ford stands as a particularly poignant chapter in their history. Under immense duress, and with their lands largely surrounded and encroached upon by non-Native settlers, the Catawba Nation ceded their entire 144,000-acre reservation to the state of South Carolina for a mere $20,000 and the promise of a small amount of land elsewhere. This promise was never fully fulfilled. The Catawba were left with only a small, 600-acre parcel of land, a fraction of their once vast domain, near their traditional core. "It was an act of survival, not surrender," a tribal historian once remarked, highlighting the impossible choice faced by the leaders of that era. "They had no other options left."

Resilience in the Face of Dispossession: The 19th and 20th Centuries

Despite the dramatic loss of land, the Catawba clung tenaciously to their identity and their small remaining territory. Pottery, with its distinctive red-clay sheen, became more than just a craft; it was a defiant declaration of identity and a vital source of income. Women, in particular, maintained this ancient art form, traveling to nearby towns to sell their wares, keeping a vital cultural link alive.

The 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by poverty, isolation, and continued struggles for self-determination. In a unique historical development, many Catawba converted to Mormonism in the late 19th century, a decision that provided spiritual solace and, in some cases, educational opportunities, but also added another layer to their complex cultural identity.

In 1959, the federal government, under its controversial "termination policy," officially ended its relationship with the Catawba Nation, effectively dissolving their tribal status and leaving them without federal services or recognition. This policy, designed to assimilate Native Americans, was catastrophic for many tribes. For the Catawba, it meant further hardship and a renewed fight for their very existence as a distinct people.

Reclaiming Their Place: The Modern Catawba Nation

The spirit of the Catawba, however, proved indomitable. Through decades of relentless legal and political advocacy, the Catawba Nation fought to reclaim what was rightfully theirs. The re-establishment of federal recognition in 1993 marked a monumental turning point. This hard-won victory, solidified through a landmark land claims settlement with the state of South Carolina and the federal government, provided a foundation for the tribe’s resurgence.

Today, the Catawba Nation’s federally recognized land base remains relatively small, centered around the 600-acre reservation in York County, South Carolina, just south of Rock Hill. However, the 1993 settlement also included provisions for the tribe to acquire additional lands in trust, allowing them to expand their economic development opportunities and provide for their members.

The modern Catawba Nation is a testament to cultural revitalization and economic self-sufficiency. They are actively working to preserve their language (though largely dormant, revitalization efforts are underway), teach traditional crafts like pottery, and reconnect younger generations with their heritage. Economic ventures, including the development of a casino, are providing vital resources for tribal programs, healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

The "where" of the Catawba Nation today is therefore multifaceted. It is the modest acreage of their reservation, a hard-won symbol of their sovereignty. It is the broader ancestral territory of the Carolina Piedmont, where their history is etched into every stream and forest. And perhaps most importantly, it is in the hearts and minds of the Catawba people themselves, who, despite centuries of immense pressure and dispossession, continue to assert their right to exist, thrive, and define their own future on the lands they have always called home. Their story is a powerful reminder that "where" a people lives is not merely a geographic coordinate, but a living narrative of identity, struggle, and enduring spirit.