Where the Ocean Meets the Mountains: Unearthing the Ancient Domain of the Chumash People

SANTA BARBARA, Calif. – Where the sun-drenched beaches of Southern California meet the rugged Santa Ynez Mountains, a vibrant tapestry of human history unfolds. This isn’t just a postcard-perfect landscape; it is the ancestral heartland of the Chumash people, an indigenous nation whose deep connection to land and sea shaped one of the most sophisticated hunter-gatherer societies in North America. To ask "Where did the Chumash tribe live?" is to embark on a journey across a vast, ecologically diverse territory that spanned coasts, islands, valleys, and mountains, a domain they managed and revered for millennia.

For over 13,000 years, long before European sails dotted the horizon, the Chumash were the undisputed masters of what is now the central and southern California coast. Their territory extended roughly from present-day Malibu in the south to Estero Bay near San Luis Obispo in the north, stretching inland to the western edge of the San Joaquin Valley, and critically, encompassing the four northern Channel Islands: Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel. This vast expanse, characterized by its Mediterranean climate, rich marine life, and fertile valleys, was not merely a place of residence but a meticulously understood and sustainably managed ecosystem.

A Maritime Empire: The Ocean as a Highway

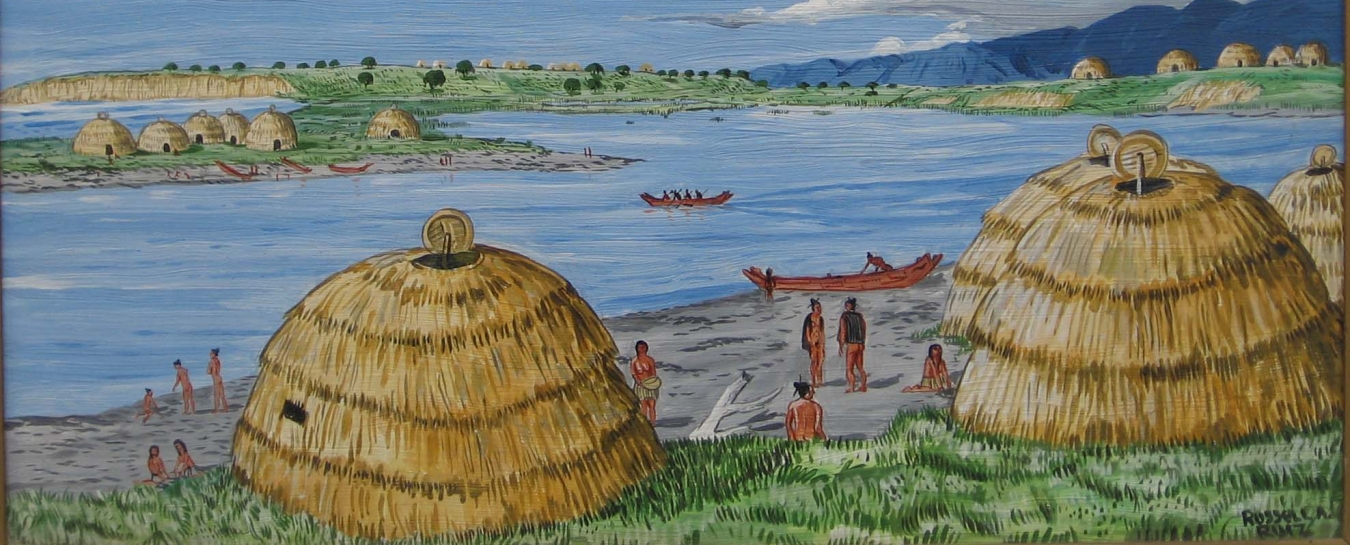

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of the Chumash domain was its intimate relationship with the Pacific Ocean. Unlike many inland tribes, the Chumash were renowned maritime experts, their lives intrinsically linked to the ebb and flow of the tides. Their mastery of the sea was epitomized by the tomol, a plank canoe unique to Southern California and a marvel of pre-contact engineering. Constructed from redwood driftwood meticulously pieced together with natural asphaltum (tar) and plant fibers, these swift, seaworthy vessels could carry multiple people and significant cargo.

"The tomol wasn’t just a boat; it was the lifeblood of our people," explains a contemporary Chumash elder, reflecting on the historical significance. "It connected our island communities with the mainland, allowed us to harvest the bounty of the ocean, and facilitated trade that stretched far beyond our immediate shores."

The ocean was a veritable pantry for the Chumash. They fished for halibut, rockfish, and abalone, utilizing sophisticated nets, hooks, and harpoons. They harvested shellfish from the intertidal zones and were skilled hunters of seals, sea lions, and even drift whales that washed ashore. The Channel Islands, visible from the mainland on clear days, were not distant outposts but integral parts of their territory, serving as fishing grounds, ceremonial sites, and sources of unique resources like chert for tools. Archaeological evidence on these islands, such as ancient middens (shell mounds), speaks volumes about the sustained presence and intensive resource utilization by the Chumash.

Inland Riches: From Mountains to Valleys

While their maritime prowess often garners the most attention, the Chumash also expertly utilized the diverse inland environments of their territory. The valleys and foothills provided an abundance of terrestrial resources. Acorns, primarily from coast live oaks and valley oaks, were a staple food, painstakingly processed to remove tannins and then ground into flour for bread or porridge. Other plant foods included seeds, berries, nuts, and roots, gathered seasonally with an intimate knowledge of the local flora.

Hunting played a vital role, with deer, rabbits, squirrels, and various birds providing protein and hides. The Chumash employed sophisticated hunting techniques, including snares, bows and arrows, and communal drives. Their land management practices were equally advanced; controlled burning, for example, was used to encourage new plant growth, clear brush, and enhance hunting grounds, demonstrating a deep understanding of ecological principles that predated modern conservation efforts by millennia.

The rugged Santa Monica and Santa Ynez Mountains, running parallel to the coast, were not barriers but integral parts of their homeland. They offered shelter, freshwater springs, and unique resources like steatite (soapstone) for carving bowls and effigies. Hidden caves and rock shelters within these mountains became canvases for their vibrant rock art, depicting spiritual beliefs, cosmological understandings, and perhaps historical events in striking polychrome murals. Sites like the Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park near Santa Barbara offer a tangible glimpse into this profound spiritual connection to the land.

Villages and Networks: A Thriving Society

The Chumash lived in numerous villages, some small and temporary, others large and permanent, strategically located near reliable water sources and abundant food. Estimates suggest a pre-contact population of up to 20,000 people, organized into distinct political units, each with its own chief (or wots) and a sophisticated social hierarchy that included nobles, commoners, and specialists like artisans, shamans, and healers.

Their territory was crisscrossed by well-maintained trails that facilitated extensive trade networks. The Chumash developed a sophisticated economic system, with shell beads (especially Olivella shell beads) serving as a form of currency, used for exchange not only within their own territory but also with neighboring tribes like the Yokuts in the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave to the east. Goods traded included dried fish, animal hides, obsidian (volcanic glass for tools), steatite, and plant products, creating a robust regional economy that bound their diverse communities together. This intricate web of trade further underscores the concept of their land not as isolated pockets, but as a cohesive, interconnected domain.

The Cataclysm of Contact: A Land Transformed

The Chumash way of life, intrinsically tied to their ancestral lands, faced an existential threat with the arrival of European explorers and, more devastatingly, the Spanish mission system. The first significant contact came with Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542, who noted the large, welcoming villages and sophisticated culture. However, it was the establishment of Spanish missions starting in the late 18th century that irrevocably altered the Chumash landscape and society.

Missions like San Buenaventura (1782), Santa Barbara (1786), and La Purísima Concepción (1787) were built directly within Chumash territory. The Chumash were forcibly relocated, their traditional lands confiscated, and their spiritual practices suppressed. Disease, forced labor, and cultural subjugation led to a catastrophic decline in population. "Our people were taken from their homes, their traditions outlawed, their language silenced," recounts a Chumash historian. "The land that had sustained them for millennia was suddenly alien, under foreign control."

Despite this immense hardship and dispossession, the Chumash people never vanished. They resisted in various ways, from quiet defiance to open rebellion, such as the 1824 Chumash Revolt, which saw them temporarily reclaim missions at Santa Inés, La Purísima, and Santa Barbara. Their resilience and deep spiritual connection to their ancestral lands ensured their survival, even as their physical domain was carved up and developed by successive waves of settlers.

An Enduring Legacy: Guardians of the Ancestral Home

Today, the question "Where did the Chumash tribe live?" is answered not just by historical maps but by the vibrant presence of their descendants. While much of their ancestral land is now privately owned or managed by state and federal entities, the Chumash people, particularly the federally recognized Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, continue to assert their rights and responsibilities as the original stewards of this territory.

They are actively engaged in cultural revitalization, language preservation, environmental protection, and the reclamation of sacred sites. Efforts are underway to reintroduce native plant species, restore traditional land management practices, and educate the public about their rich heritage. The Chumash continue to monitor and advocate for the protection of archaeological sites on the Channel Islands and along the coast, ensuring that the legacy of their ancestors is honored.

The story of where the Chumash tribe lived is not merely a geographical account; it is a profound narrative of adaptation, ingenuity, and an unparalleled bond with a diverse and bountiful landscape. From the depths of the Pacific Ocean, traversed by their magnificent tomols, to the peaks of the Santa Ynez Mountains, adorned with their sacred art, the Chumash cultivated a civilization in harmony with their environment. Their ancestral domain, now a coveted slice of California, remains a testament to their enduring spirit, reminding us that even in the face of immense change, the roots of an ancient people run deep in the land they called home.