Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the Kaw Nation’s historical and contemporary dwelling places, incorporating interesting facts and quotes.

The Shifting Sands of Home: Tracing the Kaw Nation’s Enduring Journey

The very name "Kansas" echoes with the history of the Kaw Nation, a proud and resilient Indigenous people. Often called the Kansa, meaning "People of the South Wind," their story is not one of a static homeland but a dynamic narrative of deep ancestral roots, forced displacement, profound loss, and ultimately, an inspiring resurgence. To ask "Where did the Kaw Nation live?" is to embark on a journey through centuries, across vast plains, and into the heart of a people determined to reclaim their identity and place in the world.

The Ancestral Heartland: Masters of the Prairie

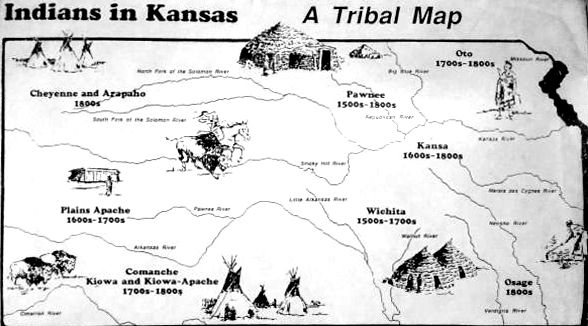

For millennia, long before European explorers charted its rivers or American settlers claimed its fertile soil, the Kaw Nation thrived in what is now the northeastern quadrant of Kansas and parts of western Missouri. Their traditional territory was immense, stretching from the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers westward along the Kansas River valley, and southward towards the Arkansas River. This was a land of rolling prairies, dotted with stands of timber along rivers and streams – an environment perfectly suited to their semi-nomadic lifestyle.

The Kaw were a Siouan-speaking people, sharing linguistic and cultural ties with other Plains tribes like the Osage, Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw. Their lives were dictated by the seasons and the rhythm of the land. They lived in earthlodge villages during the spring and fall, cultivating extensive fields of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. These permanent settlements, often strategically located near water sources and defensible positions, served as their cultural and economic hubs.

But the Kaw were also master hunters, particularly of the American bison. Twice a year, they would embark on extensive buffalo hunts, leaving their villages to follow the vast herds across the plains. These hunts were not just about sustenance; they were communal events, reinforcing social bonds, spiritual practices, and warrior traditions. The buffalo provided everything: meat for food, hides for shelter and clothing, bones for tools, and even dung for fuel. Their deep spiritual connection to the land and its creatures was paramount. As tribal elder and historian, LaDonna Brown (Caddo/Kiowa/Delaware), has often noted regarding Indigenous relationships with land, "It’s not just a place to live, it’s a part of who you are, it’s your identity." For the Kaw, their ancestral lands were infused with the spirits of their ancestors and the bounty of the Creator.

Early European accounts, though often biased, offered glimpses of the Kaw’s strength and sophistication. French explorers and traders were among the first to encounter them in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, establishing trade relationships that brought new goods like firearms and metal tools, but also devastating diseases that would decimate their populations.

The Inexorable Shrinking: Treaties and Removals

The arrival of the United States after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 marked a catastrophic turning point for the Kaw. The burgeoning American nation, driven by westward expansion and the concept of "Manifest Destiny," viewed Indigenous lands as obstacles to progress. A series of treaties, often signed under duress or through deceptive practices, systematically chipped away at the Kaw’s vast ancestral domain.

The Treaty of 1825 was the first major blow. Signed at Council Grove, a historic meeting place along the Santa Fe Trail, this treaty ceded 20 million acres of Kaw land to the U.S. government, reserving only a small tract, roughly 20 miles wide and 30 miles long, along the Kansas River. This forced concentration into a smaller area disrupted their traditional hunting patterns and agricultural practices, making self-sufficiency increasingly difficult. The Kansa were becoming reliant on government annuities and goods, a deliberate policy designed to control and "civilize" them.

The pressure intensified. White settlers, emboldened by the prospect of free land, encroached on the remaining Kaw territories, often disregarding treaty boundaries. Disease continued to ravage the population, and the buffalo herds, their lifeblood, were being decimated by relentless hunting from both white and Indigenous peoples.

By the Treaty of 1846, the Kaw were forced to cede even this diminished reservation, moving to a smaller tract near Council Grove, Kansas, along the Neosho River. This move was particularly difficult, as it placed them in direct proximity to the growing stream of emigrants on the Santa Fe Trail, leading to increased conflicts and further erosion of their cultural practices.

But the final, most devastating removal came with the Treaty of 1872-1873. Under the terms of this agreement, the Kaw Nation was compelled to abandon all their remaining lands in Kansas and relocate to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This was part of the broader federal policy of Indian Removal, which forcibly displaced numerous tribes from their ancestral homes east of the Mississippi and from the Great Plains.

The journey to Oklahoma was a testament to the Kaw’s resilience in the face of immense suffering. Led by figures like Chief Allegawaho, a prominent Kaw leader during this tumultuous period, the approximately 600 remaining Kaw people undertook the arduous trek. Allegawaho famously stated, "We are a small tribe, and we have been shoved about like a leaf in the wind." The journey was fraught with hardship, disease, and starvation, further reducing their numbers. They settled on a small reservation in what would become Kay County, Oklahoma, near the present-day town of Kaw City.

Oklahoma: A New, Hard-Won Home

Life in Indian Territory presented a new set of challenges. The Kaw had to adapt to a different environment and compete for resources with other displaced tribes. The federal government intensified its assimilation policies, pressuring the Kaw to abandon their language, spiritual practices, and traditional way of life in favor of American farming methods, Christianity, and English. Boarding schools, designed to "kill the Indian to save the man," forcibly enrolled Kaw children, further severing cultural ties.

The Dawes Act of 1887 delivered another blow. This act dismantled communal tribal land ownership, allotting individual parcels to tribal members and opening up "surplus" lands to non-Native settlers. For the Kaw, this meant the further fragmentation of their land base and the loss of the communal ties that had sustained them for generations. By the early 20th century, the Kaw Nation’s population had dwindled to just a few hundred people, and their future seemed precarious.

However, even in these darkest times, seeds of resilience were being sown. A remarkable figure emerged from the Kaw Nation: Charles Curtis. Born in 1860 on the Kaw reservation in Kansas, Curtis, a Kaw descendant, would rise through the ranks of American politics to become the Vice President of the United States under Herbert Hoover (1929-1933). His story is a powerful, if complex, example of an individual navigating the two worlds and achieving prominence in the very system that had so oppressed his people. While his political actions often aligned with assimilationist policies, his very presence in such a high office underscored the enduring spirit of Native Americans.

Resurgence and Reclamation: Returning to the Ancestors

The mid-20th century brought a slow but steady shift in federal Indian policy, moving away from termination and assimilation towards self-determination. For the Kaw Nation, this marked the beginning of a remarkable journey of cultural revitalization and a symbolic, and sometimes literal, return to their ancestral lands.

Today, the Kaw Nation’s headquarters are located in Kaw City, Oklahoma. With a tribal enrollment of over 3,000 members, the Nation has focused on rebuilding its infrastructure, economy, and cultural programs. Economic ventures, including gaming (SouthWind Casino), have provided crucial revenue for tribal services, health care, education, and elder care.

Crucially, the Kaw Nation has also dedicated significant resources to reclaiming and honoring their history in Kansas. One of the most poignant examples is the Allegawaho Memorial Park near Council Grove, Kansas. This 167-acre site, purchased by the Kaw Nation in 2002, is not just a park; it’s a sacred space. It encompasses the last Kaw reservation in Kansas, the site of the tribe’s final Kaw Agency, and the final resting place of Chief Allegawaho and other tribal members.

The reacquisition of this land was a monumental achievement, a tangible link to their past. It serves as a place of healing, remembrance, and cultural reconnection. The Kaw Nation holds annual powwows and ceremonies there, bringing tribal members back to the heart of their ancestral domain. As Kaw Nation Chairwoman Lynn Williams stated upon the park’s dedication, "This land is a part of our soul. It’s where our ancestors walked, lived, and died. To be able to bring it back into tribal ownership is a dream come true."

Furthermore, the Kaw Nation is actively involved in preserving their language, Kansa, through linguistic programs and educational initiatives. They are also working to protect and interpret other significant historical sites in Kansas, ensuring that their story is accurately told and remembered. The renaming of the Kansas River to the Kansa River, a movement gaining momentum, is another powerful symbol of this desire to reclaim and honor their heritage.

An Enduring Presence

The question "Where did the Kaw Nation live?" is therefore answered not with a simple geographical pinpoint, but with a profound narrative of movement, resilience, and an unwavering connection to identity. They lived, and continue to live, in the vast prairie lands of Kansas, where their name is etched into the very fabric of the state. They live in the Oklahoma lands that became their refuge and new home. And most importantly, they live in the hearts and minds of their descendants, who carry forward the spirit of the "People of the South Wind."

The Kaw Nation’s journey is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples, a story of survival, adaptation, and the relentless pursuit of self-determination. Their past is etched into the landscape of America, and their future, vibrant and self-determined, continues to unfold, honoring the ancestors while forging new paths for generations to come.