The Enduring Echoes of Lenapehoking: Unraveling the True Geography of a Nation’s Home

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

The concrete canyons of Manhattan, the bustling boardwalks of New Jersey, the serene farmlands of Pennsylvania, and the historic streets of Delaware—these landscapes are etched into the American consciousness. Yet, beneath the asphalt and the meticulously tilled soil lies a deeper, older story, one of a people whose very identity was woven into these lands for millennia: the Lenape.

To ask "Where did the Lenape live?" is to embark on a journey that transcends simple geography. It’s to peel back layers of colonial conquest, forced migration, and enduring resilience. It’s a story not of a static point on a map, but of a dynamic, living relationship with a vast and vibrant territory, a relationship that persists even today, long after the last of their ancestral fires were extinguished by encroaching European settlements.

Lenapehoking: The Heart of a Nation

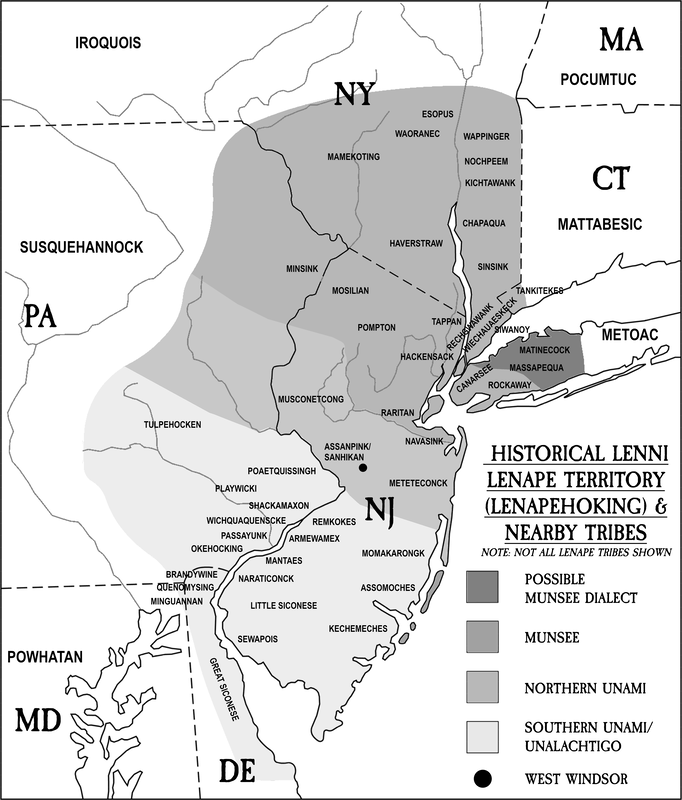

Before the arrival of European ships in the early 17th century, the Lenape, or Lenni-Lenape (meaning "Original People" or "True People"), thrived across a vast territory they called Lenapehoking. This ancestral homeland stretched from the lower Hudson River Valley in modern-day New York, through all of present-day New Jersey, southeastern Pennsylvania, and northern Delaware. Its boundaries were not rigid lines on a survey map, but rather fluid, understood by the rivers, mountains, and the patterns of the seasons.

"Lenapehoking was our world," explains Reverend John S. Norwood, former tribal councilman and spiritual leader of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation in Bridgeton, New Jersey. "It was where our ancestors walked, hunted, fished, planted, and buried their dead for thousands of years. Every stream, every hill, every forest had a name, a story, a connection to our people."

This rich, diverse landscape supported a sophisticated, semi-nomadic lifestyle. The Lenape lived in harmonious balance with nature, moving seasonally between established villages. In the spring, they gathered near rivers and coastlines for fishing runs—shad, sturgeon, and herring were abundant. Summer saw them tending to their agricultural fields, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, often referred to as "the Three Sisters." As autumn arrived, they moved inland for hunting deer, bear, and turkey, and gathering nuts and berries. Winters were spent in sheltered longhouses, relying on stored provisions and the bounty of the land.

The Lenape were not a monolithic entity but comprised several distinct, though related, groups or "clans," often identified by their geographic location within Lenapehoking and their linguistic dialects:

- Munsee (or Minsi): Residing in the mountainous northern regions, primarily along the upper Delaware and Hudson Rivers (modern-day northern New Jersey, southeastern New York, and northeastern Pennsylvania). Their name means "People of the Stony Country."

- Unami: Occupying the central Lenapehoking, including the Delaware River Valley (modern-day southern New Jersey, southeastern Pennsylvania, and northern Delaware). Their name translates to "People Downriver."

- Unalachtigo: Located in the southern reaches of Lenapehoking, stretching to the Delaware Bay (modern-day southern New Jersey and northern Delaware). Their name means "People who Live Near the Ocean."

These groups shared a common language family (Algonquian), cultural practices, and a deep spiritual connection to their land. Their social structure was matriarchal, with women holding significant power in decision-making and land stewardship. Their understanding of land ownership was communal, based on usufruct—the right to use and benefit from the land, not to exclusively possess it. This fundamental difference would prove to be a catastrophic point of misunderstanding with the arriving Europeans.

The Dawn of Contact and the Seeds of Displacement

The 17th century brought a seismic shift to Lenapehoking. Dutch explorers like Henry Hudson sailed into Lenape waters in 1609, followed by Swedish and then English colonists. Initial interactions were often driven by trade—furs for European goods like tools, textiles, and alcohol. But soon, the Europeans’ insatiable desire for land overshadowed any peaceful exchange.

The infamous purchase of Manhattan Island by Peter Minuit for the Dutch in 1626, supposedly for 60 Dutch guilders worth of trinkets, exemplifies the tragic clash of cultures. While Europeans saw this as a definitive transfer of ownership, the Lenape likely understood it as an agreement to share resources or allow temporary settlement, an understanding consistent with their concept of land use. The idea of permanently "selling" land was utterly alien.

As more Europeans arrived, their settlements expanded rapidly. Diseases like smallpox, to which the Lenape had no immunity, ravaged their communities, weakening their numbers and their ability to resist. The Lenape, caught between the competing colonial powers—Dutch, Swedish, and English—found their ancestral lands shrinking under a relentless tide of European encroachment.

The Long Walk West: A Trail of Broken Promises

The 18th century marked an accelerated period of displacement. Pennsylvania, founded by William Penn on principles of fair dealings with Native Americans, initially offered a glimmer of hope. Penn genuinely sought to purchase land through treaties, and for a time, relations were relatively peaceful. However, after Penn’s death, his sons and colonial administrators adopted more aggressive and often fraudulent tactics.

The most notorious example is the "Walking Purchase" of 1737. This purported treaty claimed to grant Pennsylvania land as far as a man could walk in a day and a half. The Lenape believed this meant a leisurely stroll; instead, the colonial authorities hired three swift runners who covered an astonishing 65 miles, claiming a vast swath of prime Lenape territory. This act, a blatant betrayal, irrevocably shattered trust and forced many Lenape to abandon their homes.

"The Walking Purchase was a wound that never healed," says Curtis Zunigha, co-director of the Lenape Center in New York City and an enrolled member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. "It wasn’t just land; it was our connection to our ancestors, our sacred sites, our very identity being ripped away."

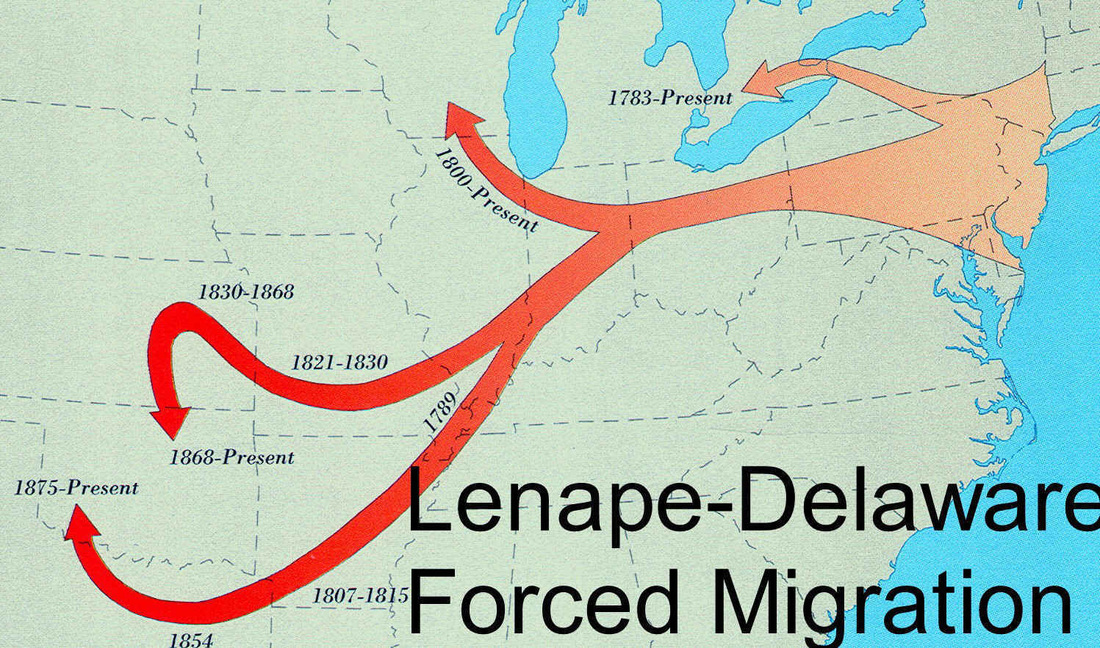

Driven by relentless pressure, the Lenape were pushed westward, across the Susquehanna River into the Ohio Valley. Here, they attempted to rebuild, but the pressures continued. They became entangled in colonial conflicts like the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, often caught between warring factions, each promising land and protection, only to betray them later.

The Scattered Nation: A Diaspora Across North America

The early 19th century saw the Lenape forced into a series of traumatic removals, a diaspora that scattered their people across vast distances. Treaties, often signed under duress or through deceptive means, mandated their relocation, first to Indiana, then Missouri, and finally, for many, to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

Today, the largest federally recognized Lenape communities reside far from Lenapehoking:

- The Delaware Tribe of Indians (Oklahoma): Descendants of the Unami and Unalachtigo.

- The Delaware Nation (Oklahoma): Another large Lenape community, also descended primarily from the Unami.

- The Stockbridge-Munsee Community (Wisconsin): Descendants of the Munsee who were converted by missionaries and migrated westward alongside other Algonquian groups.

Beyond the United States, significant Lenape communities also exist in Canada, where groups who allied with the British during the American Revolution were granted land:

- Munsee-Delaware Nation (Ontario, Canada): Descendants of Munsee speakers.

- Moravian of the Thames First Nation (Ontario, Canada): Another Munsee-speaking community.

- Delaware of the Six Nations of the Grand River (Ontario, Canada): A smaller Lenape community living within the larger Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy.

While these are the largest recognized groups, smaller Lenape communities and individuals also exist in their ancestral homelands, often unrecognized by federal governments but maintaining their cultural identity and advocating for their heritage. Groups like the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation in New Jersey and the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware are examples of communities striving for recognition and cultural revitalization in their traditional territories.

Reclaiming Identity and Returning Home

Despite the historical trauma of displacement, the Lenape people have demonstrated remarkable resilience. In Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Canada, they have maintained their languages, traditions, and sovereignty. They hold powwows, teach their children the Lenape language, and work to preserve their cultural heritage.

But the call of Lenapehoking remains strong. In recent years, there has been a growing movement among Lenape descendants to reconnect with their ancestral lands. This includes:

- Cultural Exchange: Tribal members from Oklahoma and Canada visit New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania to conduct ceremonies, educate the public, and build relationships with local communities.

- Language Revitalization: Efforts are underway to teach the Munsee and Unami dialects, both critically endangered, to new generations.

- Land Back Initiatives: While large-scale land repatriation is complex, there are efforts to acquire small parcels of land for cultural centers, ceremonial sites, or burial grounds within Lenapehoking. The Lenape Center in New York City, for example, is actively working to raise awareness and foster a Lenape presence in their original homeland.

- Historical Recognition: Advocates push for greater acknowledgement of Lenape history in schools, museums, and public spaces in the Mid-Atlantic region.

"Our ancestors never truly left Lenapehoking," says Brent Stonefish, a member of the Munsee-Delaware Nation in Canada, during a recent visit to New York. "Their spirits are still here, in the rivers, in the soil. For us to return, even for a visit, is to honor them and to ensure that our future generations know where they come from."

The Enduring Legacy

The question "Where did the Lenape live?" is no longer just a historical inquiry; it’s a profound statement about persistence, identity, and the ongoing relationship between people and place. The legacy of the Lenape is not merely a footnote in American history; it is foundational. Their names echo in the very fabric of the landscape: Manhattan, Hackensack, Passaic, Raritan, Neshaminy, Pocono – all derived from Lenape words.

By understanding where the Lenape lived, we begin to understand the true, complex history of the land we now inhabit. It compels us to look beyond the present-day boundaries and recognize the deep, enduring connection of the Lenape to Lenapehoking—a connection that, despite centuries of displacement, continues to shape their identity and their tireless efforts to return, culturally and spiritually, to the heart of their original home. Their story reminds us that land is not just property, but the living memory of a people.