The Enduring Homeland: Tracing the Shifting Territories of the Sioux Nation

To ask "Where did the Sioux live?" is to embark on a journey through centuries of dynamic movement, profound spiritual connection to land, and a harrowing saga of displacement. Far from being confined to a single, static location, the Sioux people – more accurately known as the Oceti Sakowin or "Seven Council Fires" – inhabited and traversed a vast, ever-changing territory across the North American heartland. Their history is not merely a geographic account but a testament to adaptation, resilience, and an unbreakable bond with the land that shaped their identity, culture, and destiny.

The story of the Oceti Sakowin’s homeland begins not on the windswept plains, as is commonly imagined, but in the lush woodlands of what is now the upper Midwest. Prior to European contact, the ancestors of the Sioux resided in the region around the Great Lakes, particularly near the headwaters of the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota and Wisconsin. Here, they were primarily a semi-sedentary people, living in villages, practicing a mix of horticulture (growing corn, beans, and squash), hunting deer and elk, fishing, and gathering wild rice. This early lifestyle was characterized by a deep knowledge of the forest and riverine ecosystems, a stark contrast to the equestrian nomadic culture they would later adopt.

However, the arrival of European traders and settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries dramatically altered the geopolitical landscape. The introduction of firearms to various Indigenous nations intensified inter-tribal warfare. Pressure from the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe), who had earlier access to French firearms and were expanding westward, gradually pushed the Oceti Sakowin out of their traditional woodland territories. This westward migration was not a single, sudden exodus but a gradual, centuries-long process, driven by both conflict and opportunity.

As the Oceti Sakowin moved further west, they encountered the vast expanse of the Great Plains. This new environment presented both challenges and immense opportunities. The defining transformation came with the introduction of the horse, brought to the Americas by the Spanish. By the early 18th century, horses had spread north, reaching the Sioux and revolutionizing their way of life. The horse enabled them to efficiently hunt the immense buffalo herds that roamed the plains, providing not only food but also hides for tipis and clothing, bones for tools, and dung for fuel.

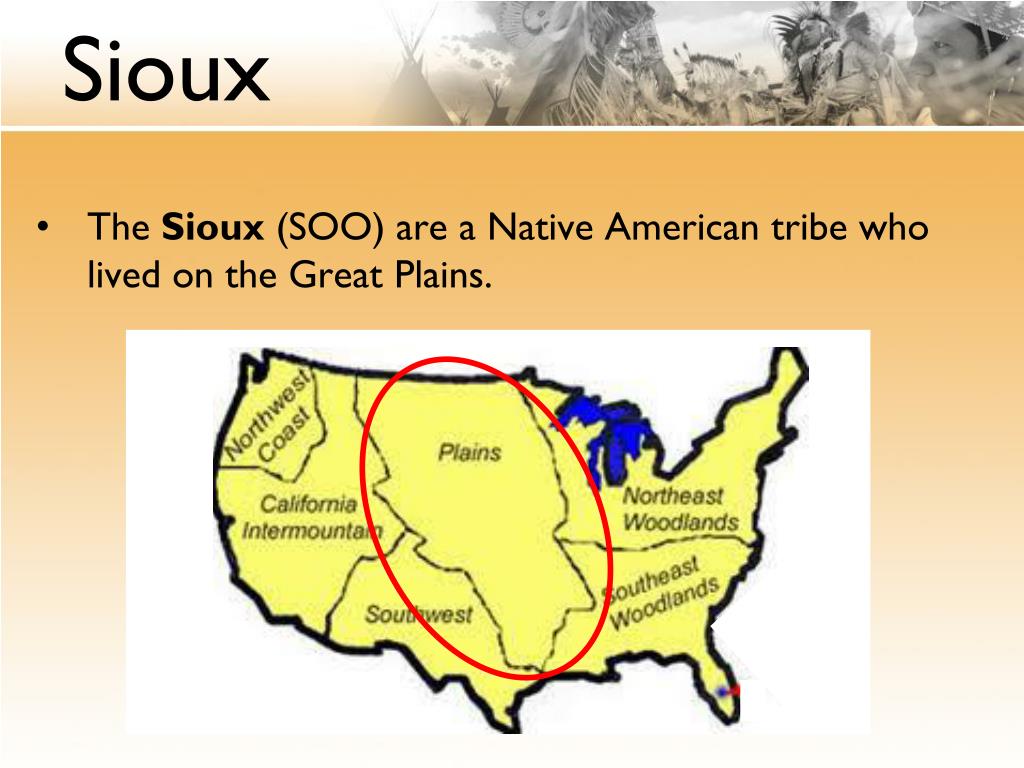

This new equestrian culture fostered a highly mobile, nomadic lifestyle. The Oceti Sakowin became master hunters and warriors, their society organized around the seasonal movements of the buffalo. Their territory expanded dramatically, stretching across what would become the Dakotas, western Minnesota, northern Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, and southeastern Montana. This vast domain was not a fixed boundary but a fluid sphere of influence, contested and shared with other Plains nations like the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, and Pawnee.

Within the Oceti Sakowin, distinct groups emerged, primarily differentiated by dialect:

- The Dakota (Isanti and Sisseton/Wahpeton): Often referred to as the "Eastern Dakota," they remained closer to their woodland origins, inhabiting areas in Minnesota and eastern Dakotas. While they adopted some aspects of Plains culture, their lifestyle retained more of their semi-sedentary roots.

- The Nakota (Yankton and Yanktonai): Known as the "Middle Sioux," they occupied territories in the central Dakotas and northeastern Nebraska, serving as a bridge between the Eastern Dakota and the Western Lakota, incorporating elements of both woodland and plains traditions.

- The Lakota (Teton): The "Western Sioux" became the quintessential Plains Indians, their name synonymous with the nomadic buffalo hunters. Comprising bands such as the Oglala, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Sicangu (Brulé), Oohenumpa (Two Kettles), Itazipco (Sans Arc), and Sihasapa (Blackfeet), they dominated the western plains, their heartland centered around the sacred Black Hills.

The Black Hills, or Paha Sapa in the Lakota language, stand as the spiritual and geographical epicenter of the Lakota world. Located in what is now western South Dakota and northeastern Wyoming, these pine-clad mountains rise dramatically from the surrounding plains, a stark contrast to the flat grasslands. For the Lakota, Paha Sapa was more than just a hunting ground or a refuge; it was the "heart of everything that is," a place of profound spiritual significance, where visions were sought, ceremonies performed, and sacred plants gathered. It was considered the origin point of life, a place of renewal and connection to the Great Spirit. "The Black Hills are the sacred center of the world," famously stated Lakota holy man Black Elk. "And you that are here, you are in the center of the world. And the center of the world is everywhere."

This spiritual heartland, however, would become the flashpoint for the most devastating conflicts with the encroaching United States. As American westward expansion gained momentum in the mid-19th century, driven by Manifest Destiny and the insatiable demand for land and resources, the vast territories of the Sioux became increasingly coveted.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 was the first major attempt by the U.S. government to define tribal territories and establish peace among the Plains nations. It recognized a vast Sioux territory encompassing much of the Dakotas, eastern Wyoming, and Nebraska. However, the treaty was flawed from its inception, signed by a limited number of chiefs who did not necessarily represent all bands, and quickly undermined by the relentless flow of settlers, gold miners, and railroad builders across Indigenous lands.

The escalating tensions led to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, a more comprehensive agreement designed to end Red Cloud’s War, a successful campaign by the Lakota and their allies against U.S. military forts. This treaty established the "Great Sioux Reservation," a smaller but still substantial territory encompassing most of western South Dakota, including the sacred Black Hills, which were explicitly designated as "unceded Indian territory," closed to white settlement. For a brief period, it seemed the Lakota had secured their most cherished lands.

Yet, this peace was short-lived. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, confirmed by George Armstrong Custer’s expedition, unleashed a torrent of prospectors into the protected Lakota lands. The U.S. government, despite its treaty obligations, made little effort to stop the influx, effectively abandoning its commitments. When the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies refused to sell the Black Hills, the U.S. launched a military campaign to force them onto reservations. This led to the Great Sioux War of 1876-77, a series of battles including the iconic Battle of Little Bighorn, where a coalition of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, led by figures like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, decisively defeated Custer’s 7th Cavalry.

Despite this monumental victory, the numerical and technological superiority of the U.S. military ultimately prevailed. By 1877, the Lakota were forced to relinquish the Black Hills and were confined to much smaller reservations within the Great Sioux Reservation’s original boundaries. As Red Cloud, the Oglala Lakota chief, lamented, "They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it."

The reservation era marked a profound and traumatic shift in the Sioux way of life. Their vast, mobile homelands were replaced by fixed, often arid, tracts of land. The buffalo herds, their economic and cultural lifeblood, were systematically decimated by hunters hired by the government and railroad companies, effectively starving the Sioux into submission. Traditional governance structures were undermined, and children were often sent to boarding schools designed to "civilize" them by stripping away their language and culture.

Today, the descendants of the Oceti Sakowin primarily reside on various reservations and communities across their historical range. These include:

- In South Dakota: Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (Oglala Lakota), Rosebud Indian Reservation (Sicangu Lakota), Cheyenne River Indian Reservation (Miniconjou, Itazipco, Sihasapa, Oohenumpa Lakota), Standing Rock Indian Reservation (Hunkpapa Lakota, Yanktonai Dakota – shared with North Dakota), Crow Creek Indian Reservation (Lower Yanktonai Dakota), Lower Brule Indian Reservation (Sicangu Lakota), Flandreau Santee Sioux Reservation (Isanti Dakota), Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota).

- In North Dakota: Standing Rock Indian Reservation, Spirit Lake Nation (Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota).

- In Minnesota: Upper Sioux Community, Lower Sioux Indian Community, Prairie Island Indian Community, Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (all Isanti Dakota).

- In Nebraska: Santee Sioux Nation (Isanti Dakota).

- In Montana: Fort Peck Indian Reservation (shared with Assiniboine, including some Hunkpapa Lakota and Yanktonai Dakota).

- In Canada: Many Dakota and Lakota people sought refuge in Canada after the U.S. wars, establishing communities in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

These reservations, while sovereign nations, are often economically challenged due to historical injustices, land loss, and broken treaties. Yet, they remain vital centers of cultural preservation, language revitalization, and self-determination. The Sioux people continue to assert their rights, including ongoing legal battles for the return of the Black Hills or just compensation, recognizing that the land holds not just resources, but the very essence of their identity.

The question "Where did the Sioux live?" therefore elicits a complex answer: from the woodlands of Minnesota to the vast buffalo plains, with the Black Hills as their sacred heart. Their homeland was a dynamic entity, shaped by migration, adaptation, and fierce defense. Though confined to reservations, their connection to the ancestral lands remains profound, a testament to a people whose spirit, like the enduring prairie winds, continues to sweep across the heart of a continent. Their journey is a powerful reminder that "home" for Indigenous peoples is not merely a geographic point, but a living, breathing landscape interwoven with history, spirituality, and an enduring legacy of resilience.