Where Legends Bleed: The Ballad of Walla Walla and America’s Unfinished Stories

America is a nation built on legends – tales of pioneering spirit, manifest destiny, and the relentless march of progress. From the mythical frontiersmen to the iconic outlaws, these narratives shape our understanding of who we are. Yet, beneath the grand epics, there lie darker, more complex legends, etched not in triumphant bronze but in the very soil of forgotten battlefields. One such legend, often overshadowed by the more celebrated conflicts of westward expansion, is the brutal and pivotal Battle of Walla Walla in December 1855. It is a story where the clash of cultures reached a bloody crescendo, leaving behind a legacy of trauma, resistance, and a profound re-evaluation of the American dream.

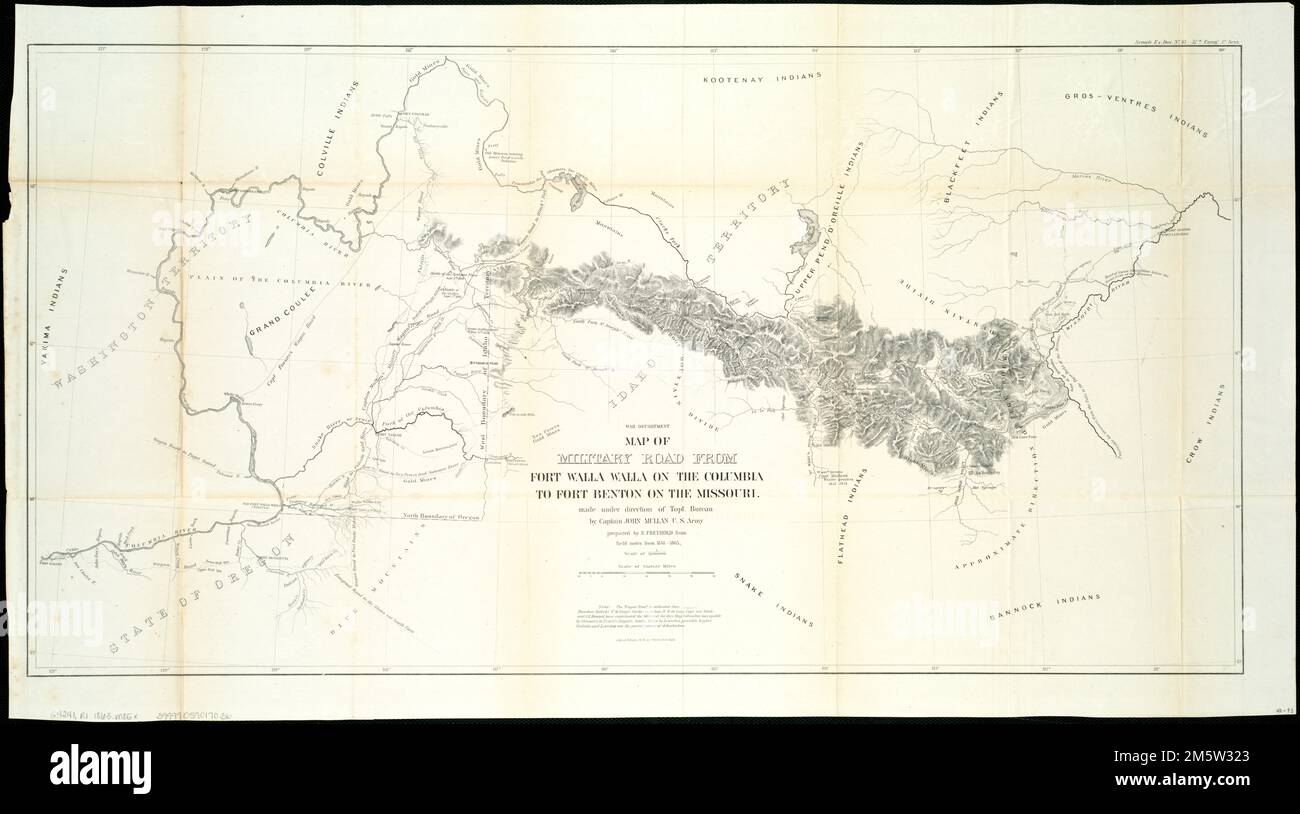

To understand the legend of Walla Walla, one must first grasp the shifting landscape of the mid-19th century Pacific Northwest. For millennia, the fertile valleys and abundant rivers of what would become Washington Territory were home to the Confederated Tribes: the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Palouse, and most prominently, the Yakama. Their lives were interwoven with the land, governed by ancient traditions, seasonal migrations, and a deep spiritual connection to their ancestral territories. The arrival of Euro-American fur traders, missionaries, and eventually, settlers, marked the beginning of an irreversible transformation. Initial interactions were often a mix of curiosity and cooperation, but the trickle of newcomers soon became a flood, driven by the fervent belief in Manifest Destiny – the idea that it was America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent.

The catalyst for the eruption of violence in the Walla Walla Valley was the discovery of gold in the Colville region in 1855. This sparked a frenzied rush of prospectors who, ignoring established tribal boundaries, swarmed across Indigenous lands, disrupting traditional hunting grounds, polluting rivers, and sowing chaos. Compounding this volatile situation was the series of treaties orchestrated by Governor Isaac Stevens of Washington Territory. In May and June of 1855, Stevens convened the Walla Walla Council, a gathering of immense historical significance where he pressured tribal leaders to cede vast tracts of their ancestral lands in exchange for reservations.

For many tribal leaders, the council was a charade. They understood the implications of Stevens’s proposals – the loss of sovereignty, the confinement to small, unfamiliar territories, and the destruction of their way of life. Chief Peopeo Moxmox (Yellow Bird) of the Walla Walla tribe, a powerful and respected leader, famously expressed his defiance during the council: "You have spoken in a loud voice. We have listened carefully. Now, it is our turn to speak." His words, and those of other chiefs like Kamiakin of the Yakama, conveyed a deep mistrust of American intentions and a fierce determination to protect their people and their lands. Despite their protests, Stevens, leveraging a combination of intimidation and dubious legal maneuvering, secured signatures on treaties that many tribal leaders later claimed they did not fully understand or agree to. These unratified treaties, combined with the relentless encroachment of miners and settlers, set the stage for war.

Tensions escalated rapidly throughout the summer and fall of 1855. Isolated attacks by both sides became more frequent, and the murder of Indian Agent Andrew Bolon by a Yakama warrior further inflamed the situation. In response, Washington Territory raised a force of volunteer militia, under the command of Colonel James K. Kelly. His mission: to assert American authority, protect settlers, and punish the "hostile" tribes. Kelly’s force, a mix of seasoned frontiersmen and eager but inexperienced volunteers, marched into the Walla Walla Valley in early December, anticipating a decisive confrontation. They would not be disappointed.

The Battle of Walla Walla, which raged from December 7th to the 10th, 1855, was not a single, grand engagement but a series of brutal skirmishes, ambushes, and a desperate siege. The Confederated Tribes, led by experienced warriors like Peopeo Moxmox and Kamiakin, utilized their intimate knowledge of the terrain to their advantage. They employed guerrilla tactics, drawing the volunteers into unfavorable positions, making the most of the dense brush, ravines, and the winding Touchet River.

On December 7th, Kelly’s forces encountered a large contingent of warriors led by Peopeo Moxmox. What followed was a multi-day ordeal for the volunteers. The tribes initially surrounded Kelly’s men, who were forced to fortify a position near a trading post. The fighting was intense and relentless. "The Indians fought with a desperation and bravery that was truly remarkable," wrote one contemporary observer, highlighting the fierce resistance faced by the American forces. The terrain made cavalry charges difficult, and the volunteers found themselves constantly under fire, their supply lines stretched thin.

The most enduring and tragic legend of the battle centers around Chief Peopeo Moxmox. On the second day of fighting, Peopeo Moxmox, perhaps attempting to negotiate or to draw out the enemy, rode towards the American lines, allegedly under a flag of truce, or at least with the understanding that he would be treated as an emissary. He was taken prisoner. What happened next remains a point of deep historical contention and a stark symbol of the era’s brutality. Accounts vary, but the consensus is that the Chief, along with several other captured warriors, was held by Kelly’s men. During a subsequent skirmish, some accounts claim Peopeo Moxmox attempted to escape or was perceived as inciting his warriors, while others suggest he was simply executed in cold blood by enraged volunteers. "It was a dark blot on the escutcheon of the volunteers," one historian later wrote, referring to the killing of a prisoner. Peopeo Moxmox was shot, then scalped, and his ears reportedly cut off as trophies – a barbaric act that horrified even some within the volunteer ranks and became a rallying cry for the tribes.

His death, far from quelling the resistance, ignited a renewed fury among the Confederated Tribes. The battle continued with ferocity. The volunteers, despite their numerical advantage and superior weaponry, struggled against the determined defense and tactical prowess of the Indigenous warriors. The fighting was close-quarters, often hand-to-hand, and the casualty count mounted on both sides. Exact numbers are difficult to ascertain due to the nature of the conflict and the biases of historical records, but estimates suggest dozens of lives were lost, with many more wounded.

By December 10th, after days of continuous engagement, the tribal forces strategically withdrew, melting back into the landscape they knew so intimately. Colonel Kelly’s men claimed victory, having held their ground and inflicted casualties, but it was a costly and inconclusive triumph. The Battle of Walla Walla did not end the war; rather, it was a pivotal engagement in the larger Yakima War (1855-1858), a conflict that would rage for several more years and profoundly reshape the Pacific Northwest.

The legend of Walla Walla endures not as a simple tale of victory or defeat, but as a stark testament to the devastating consequences of westward expansion and the clash of irreconcilable worldviews. For the American settlers and the military, it was a battle against "savagery" to secure a new frontier, a necessary step in the nation’s growth. For the Confederated Tribes, it was a heroic stand against invasion, a desperate attempt to protect their homes, their culture, and their very existence. The murder of Peopeo Moxmox, in particular, became a symbol of betrayal and unchecked violence, a wound in the collective memory that would fester for generations.

In the aftermath of the Yakima War, the tribes were eventually subdued. The promised reservations became a reality, often far smaller and less hospitable than their ancestral lands. Their populations decimated by war and disease, their traditional ways of life disrupted, the survivors faced a future of forced assimilation and cultural suppression. The Walla Walla Valley, once a vibrant hub of Indigenous life, was transformed into agricultural land, eventually becoming known for its fertile soil and, ironically, its vineyards.

Today, the Battle of Walla Walla is a complex and often painful legend. It challenges the romanticized narratives of American history, forcing us to confront the uncomfortable truths of conquest and the profound suffering inflicted upon Indigenous peoples. It reminds us that legends are not always about glorious triumphs, but also about profound losses, unfulfilled promises, and the enduring resilience of those who resisted.

The land around Walla Walla still whispers these stories. Efforts are now underway to reclaim and honor these narratives, to ensure that the voices of Peopeo Moxmox and his people are heard alongside those of the settlers. Monuments, educational programs, and a growing commitment to historical reconciliation aim to provide a more complete and honest accounting of this pivotal moment.

The Battle of Walla Walla, then, is more than just a historical event; it is a living legend, a reminder that America’s story is still being written, and that a true understanding of its past requires acknowledging all its chapters – even those stained with blood and sorrow. It stands as a powerful symbol of resistance, a tragic chapter in the expansion of a nation, and a compelling call to remember the legends that bleed, so that we may learn from them and forge a more just future.