Where the Air Thins and Fortunes are Forged: The Enduring Saga of Mining Above the Timberline

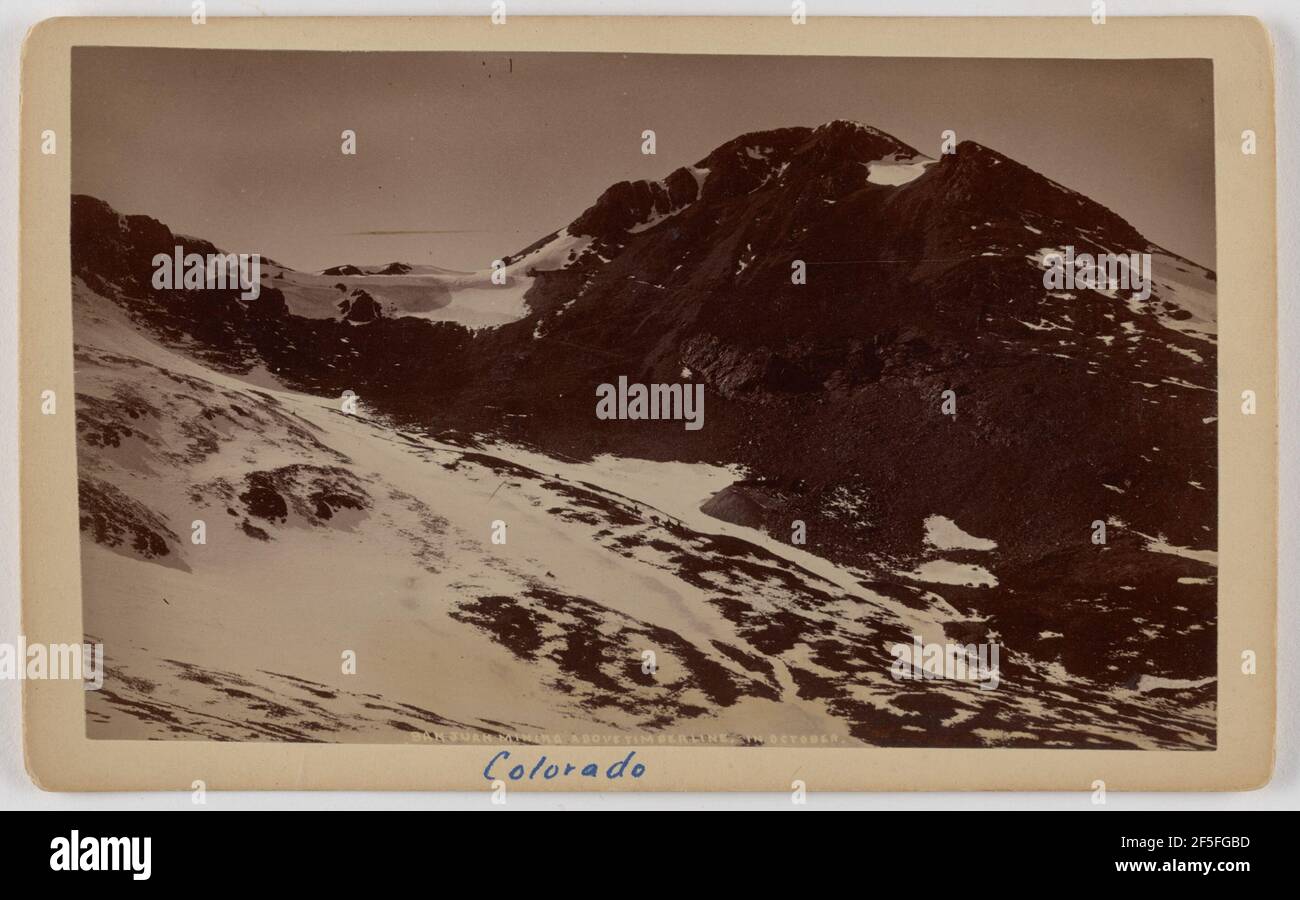

The timberline, that ethereal boundary where the last stunted trees cling to existence before the harsh alpine tundra takes over, marks a dramatic shift in the natural world. Above it, the air thins, the winds howl with primal force, and the landscape transforms into a realm of jagged peaks, perpetual snowfields, and an austere, breathtaking beauty. Yet, for centuries, this unforgiving domain has beckoned humanity, not for its serene vistas, but for the tantalizing promise of riches hidden deep within its granite heart: the minerals of the earth.

Mining above the timberline is a story of extreme challenges, unparalleled human ingenuity, immense environmental cost, and an enduring testament to our relentless pursuit of resources. It’s a narrative etched into the very fabric of mountain ranges across the globe, from the Rockies and the Andes to the Himalayas and the Arctic Circle, leaving behind a legacy of boom-and-bust towns, abandoned shafts, and landscapes forever altered.

The Allure of the Alpine Lode: A Historical Perspective

The history of high-altitude mining is often synonymous with the great mineral rushes of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Prospectors, driven by tales of gold and silver, pushed into the most remote and inhospitable corners of the world, convinced that the most difficult-to-reach places held the greatest treasures. And often, they were right.

The very geological forces that create towering mountain ranges – plate tectonics, volcanic activity, and hydrothermal processes – are also responsible for concentrating valuable minerals. As the Earth’s crust buckles and folds, heat and pressure can drive mineral-rich fluids through fissures, depositing veins of gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, and molybdenum in the high country.

Consider the American West. Towns like Leadville, Colorado, perched at over 10,000 feet, exploded from desolate camps into bustling cities in mere months. In the late 1870s, Leadville became one of the world’s richest silver camps. "The air was thin, the winters brutal, but the promise of silver was thicker than the blizzards," notes mining historian Dr. Eleanor Vance. "Men came by the thousands, defying frostbite, avalanches, and the sheer isolation for a chance at fortune." These early miners faced conditions that would send shivers down the spine of any modern worker: rudimentary tools, dangerous blasting techniques, and a complete lack of safety regulations. Lives were cheap, and the mountains claimed them without remorse.

Further south, the story of Potosí, Bolivia, at an astounding 13,420 feet (4,090 meters), offers a more ancient and sobering testament. Since its discovery in 1545, Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain) has yielded an estimated 45,000 tons of silver, becoming the primary source of wealth for the Spanish Empire for centuries. Potosí was, for a time, the largest city in the Americas. But this wealth came at an unimaginable human cost, with millions of indigenous and enslaved African laborers dying in its treacherous, oxygen-deprived mines, a dark chapter in the history of high-altitude extraction.

The Unrelenting Gauntlet: Challenges of High-Altitude Mining

The challenges of mining above the timberline are multifaceted and relentless, impacting every stage from exploration to extraction and reclamation.

-

Logistics and Access: Simply getting equipment, supplies, and personnel to these remote sites is an enormous undertaking. Roads are often non-existent or impassable for much of the year due to snow, ice, and avalanches. Historically, aerial tramways, pack animals, and even human porters were vital. Today, helicopters and specialized all-terrain vehicles assist, but costs remain exorbitant. The short operating seasons, often just a few months, add immense pressure.

-

Harsh Weather and Altitude: Extreme cold, high winds, blizzards, and thin air are constant companions. Altitude sickness (acute mountain sickness, high-altitude pulmonary edema, high-altitude cerebral edema) is a serious concern for workers, impacting productivity and posing life-threatening risks. Machinery operates less efficiently in thin air, and cold temperatures stress equipment and materials.

-

Geological Instability: Mountain environments are dynamic. Rockfalls, landslides, and avalanches are ever-present dangers. Permafrost, common in many high-altitude regions, presents unique engineering challenges. Thawing permafrost can destabilize slopes, infrastructure, and mine workings, a concern exacerbated by climate change.

-

Water Management: While seemingly abundant in the form of snow and ice, managing water in these environments is complex. Runoff can be torrential during melt seasons, leading to erosion and flooding. Conversely, water for processing can be scarce during dry periods or frozen solid for much of the year.

-

Environmental Sensitivity: The alpine ecosystem is incredibly fragile. High-altitude soils are thin and poor, vegetation grows slowly, and species are highly adapted to specific, often narrow, niches. Disturbances here take centuries to heal, if they ever do.

The Environmental Scar: A Heavy Price for Riches

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of mining above the timberline is its environmental legacy. The very beauty that draws hikers and conservationists can be irrevocably altered by mining activities.

-

Landscape Degradation: Open-pit mines create vast, gaping scars on mountain slopes, while waste rock piles (tailings) can cover acres, altering hydrology and aesthetics. Roads, power lines, and processing facilities further fragment pristine habitats.

-

Acid Mine Drainage (AMD): This is arguably the most insidious and long-lasting environmental impact. When sulfide minerals (like pyrite, "fool’s gold," which is often associated with valuable ore bodies) are exposed to air and water, they oxidize to form sulfuric acid. This acid then leaches heavy metals – such as lead, zinc, copper, arsenic, and cadmium – from the surrounding rock, creating a toxic cocktail that can pollute streams and rivers for hundreds, even thousands, of years. The notorious "yellow boy," an orange-red precipitate of iron hydroxides, often coats stream beds downstream from old mines, rendering them sterile. The infamous Summitville Mine in Colorado, a Superfund site, is a stark example of the long-term, devastating effects of AMD.

-

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Alpine species, many of which are rare or endemic, suffer from the destruction and fragmentation of their habitats. The disruption of migration corridors and breeding grounds can have cascading effects on biodiversity.

-

Dust and Noise Pollution: Mining operations generate significant dust, which can settle on snow and ice, accelerating melt and impacting air quality. Noise from blasting, heavy machinery, and transportation can disturb wildlife over large areas.

-

Water Contamination: Beyond AMD, process water used in milling and refining can contain chemicals like cyanide (used in gold extraction) or other reagents, posing further risks if not properly managed.

Modern Mining: A Shift Towards Responsibility?

In recent decades, the mining industry, spurred by stricter environmental regulations, increased public scrutiny, and corporate social responsibility initiatives, has made strides in mitigating its impact. Modern high-altitude mines are vastly different from their 19th-century predecessors.

- Technological Advancements: Drones and satellite imagery aid in precise geological mapping, reducing the footprint of exploration. Advanced drilling techniques minimize surface disturbance. Sophisticated water treatment plants are employed to neutralize AMD and remove heavy metals before discharge.

- Underground Mining: Where feasible, underground mining methods are preferred over open pits to reduce surface disturbance. The Henderson Mine in Colorado, a molybdenum mine operating almost entirely underground at over 10,000 feet, is a prime example of a modern, large-scale, deep-earth operation with a relatively small surface footprint.

- Reclamation and Remediation: Modern mining permits often mandate comprehensive reclamation plans from the outset. This includes re-contouring land, stabilizing slopes, replacing topsoil, and re-vegetating with native species. While full restoration to a pristine state is often impossible, significant efforts are made to blend the mine site back into the landscape and address ongoing pollution sources.

- Environmental Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of water quality, air quality, and wildlife populations is standard practice, allowing for adaptive management strategies.

- Community Engagement: Responsible mining companies now engage with local communities and indigenous groups, aiming to address concerns, provide economic benefits, and minimize social disruption.

However, challenges remain formidable. The sheer scale of some mineral deposits, particularly for crucial minerals like lithium and rare earths that are vital for the green energy transition, may necessitate large-scale open-pit operations, even in sensitive alpine environments. The long-term efficacy of some reclamation efforts, particularly for AMD, is still being evaluated, and the "ghosts" of historical mines continue to haunt waterways.

The Future: A Balancing Act

As the global demand for minerals continues to surge, driven by population growth and the transition to a low-carbon economy, the pressure on high-altitude mining will only intensify. The very mountains that hold these critical resources are also among the most vulnerable to climate change, with melting glaciers and thawing permafrost altering landscapes and potentially exposing new mineral deposits – or reactivating old sources of pollution.

The saga of mining above the timberline is a profound paradox. It represents both humanity’s relentless drive for progress and prosperity, and its capacity for immense environmental destruction. It is a story of grit and determination, of technological marvels carved into rock and ice. But it is also a cautionary tale of the hidden costs, of the indelible marks left on the highest, most fragile places on Earth.

The challenge for the future lies in striking an increasingly delicate balance: harnessing the wealth of the mountains responsibly, with an unyielding commitment to innovation, environmental stewardship, and social equity, ensuring that the pursuit of our material needs does not irrevocably diminish the breathtaking, vital beauty of the alpine world. The mountains will always stand, but how we choose to interact with their treasures will define their legacy, and ours.