Where the Frontier Burned: The Enduring Echoes of Fort Granville’s Fall

Today, the Juniata River flows with serene indifference through Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. Rolling hills, once dense with ancient forests, now host quiet farmlands and small towns, their names whispers of the past – Lewistown, Granville, Derry. It is a landscape that speaks of enduring peace, yet beneath its placid surface lies a history etched in fire and blood, a testament to a time when this tranquil valley was the brutal edge of the American frontier.

Here, in the summer of 1756, a small, hastily constructed stockade fort named Granville stood as a fragile bulwark against the tide of war. Its fall, a swift and savage act of destruction, was more than just a military defeat; it was a profound psychological blow that sent shivers down the spine of Pennsylvania, forever altering the course of frontier defense and igniting a brutal cycle of retaliation. The story of Fort Granville is a haunting reminder of the human cost of empire, the clash of cultures, and the relentless savagery of a war for a continent.

The Edge of Empire: Pennsylvania’s Vulnerable Frontier

The mid-18th century found Pennsylvania in a precarious position. Founded on William Penn’s Quaker principles of peace and fair dealing with Native Americans, the colony had long resisted establishing a robust military. But by the 1750s, the escalating French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years’ War) had shattered this idyllic vision. To the west, the French, allied with various Native American nations – primarily the Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee – were pushing eastward, contesting British claims and inciting raids on colonial settlements.

The Juniata Valley, fertile and alluring, had drawn a steady stream of Scots-Irish and German immigrants seeking new lives. But their presence was a violation of traditional Native American hunting grounds, exacerbated by controversial land deals like the infamous Walking Purchase of 1737. As French influence grew, these simmering grievances boiled over into open hostility.

"For years," wrote historian C. Hale Sipe in The Indian Wars of Pennsylvania, "the frontiersmen had been begging the Provincial authorities for protection, but their appeals fell largely upon deaf ears." The Quaker-dominated Assembly, slow to grasp the existential threat, finally relented after General Edward Braddock’s disastrous defeat in 1755, authorizing the construction of a chain of defensive forts stretching from the Delaware River to the Maryland border.

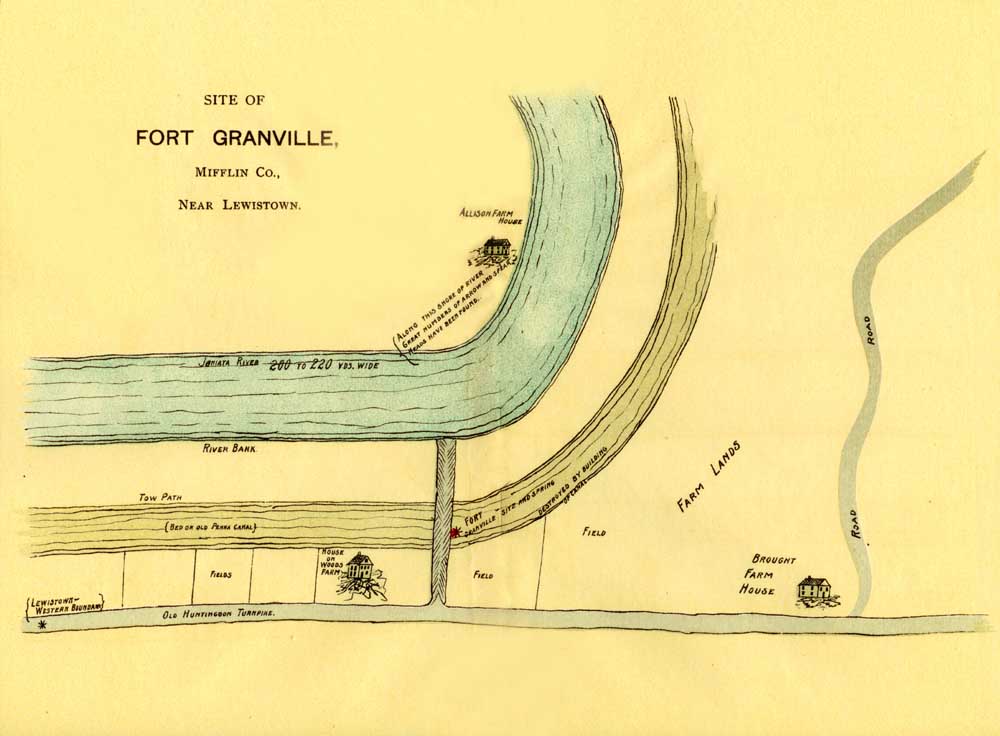

Fort Granville was one such outpost, hastily erected in the spring of 1756. Its strategic location, near the confluence of Kishacoquillas Creek and the Juniata River, was intended to guard the main trails into the Cumberland Valley and protect the exposed settlements around Lewistown. Named in honor of John Carteret, Earl Granville, a British statesman and Lord President of the Council, it was a simple stockade – a square enclosure of vertical logs, perhaps 80 to 100 feet on a side, with two small bastions, a well, and a few rudimentary barracks. It was less a formidable fortress and more a temporary refuge, manned by a small garrison of Pennsylvania Provincial Troops.

A Powder Keg Ignites: The Summer of Fear, 1756

Life on the frontier in 1756 was a constant state of terror. News of brutal raids – cabins burned, families massacred, captives dragged away – filtered through the scattered settlements, breeding a pervasive sense of dread. The forts, while offering some security, also became targets, drawing the attention of the very forces they sought to repel.

Fort Granville, under the command of Lieutenant Edward Armstrong, brother of the more famous Colonel John Armstrong (who would later lead the Kittanning Expedition), was no exception. Its garrison was chronically understaffed and undersupplied. Many soldiers were new recruits, unaccustomed to the rigors and psychological strain of frontier warfare. The fort’s location, while strategically important, was also isolated, making resupply and reinforcement difficult.

The summer of 1756 saw an escalation of hostilities. French military strategists recognized the psychological impact of striking deep into British territory. They encouraged their Native American allies, particularly the Lenape, to harass and destroy these frontier outposts, driving settlers eastward and disrupting British supply lines. The Lenape, in turn, were motivated by a desire for revenge against the encroaching colonists and a reclaiming of their ancestral lands.

The Storm Breaks: August 1756

The attack came on August 1st, 1756. A formidable force, estimated at 100 French-allied Delaware warriors and a few French soldiers, descended upon Fort Granville. They were led by the formidable Delaware chief, Captain Jacobs (Tewea), a skilled and ruthless war leader who had earned a fearsome reputation on the frontier.

The main body of the garrison, including Lieutenant Armstrong, had left the fort earlier that day, responding to a perceived threat elsewhere or perhaps on a foraging mission. This left a skeleton crew of only about 24 men under the command of Ensign John Turner. This critical misjudgment would prove fatal.

Upon their return, Armstrong and his men found the fort already under siege. A fierce engagement erupted, as the small force tried desperately to break through the attackers’ lines to reinforce the fort. They succeeded, but at a heavy cost, suffering several casualties.

The combined force inside the fort was now about 24 men, including Lieutenant Armstrong. They faced an overwhelming enemy, well-armed and determined. Contemporary accounts, later relayed by captives, paint a grim picture of the ensuing siege. The attackers surrounded the fort, pouring musket fire into the stockade and attempting to breach its walls.

"The Indians kept up a constant fire upon the fort," reported one account, "and the garrison returned it as briskly as they could." The defenders, though outnumbered, fought with desperate courage. However, Fort Granville had a critical vulnerability: its well, located outside the stockade, had been filled in by the attackers, cutting off their water supply. The summer heat, combined with the stress of combat, quickly took its toll.

The Fire and the Fall

Seeing that a direct assault was too costly, Captain Jacobs and his warriors employed a devastating tactic. They gathered bundles of dried flax and other combustibles, piling them against the fort’s wooden walls, particularly near the main gate. Under cover of intense musket fire, they set the bundles alight.

The dry timber of the stockade caught fire quickly. Flames licked up the walls, creating a terrifying inferno. The heat became unbearable, and the smoke filled the enclosure, choking the defenders. With no water to douse the flames, and the fire rapidly spreading, the situation became hopeless.

Lieutenant Armstrong, realizing the dire straits, attempted to negotiate. He offered to surrender if the lives of his men would be spared. Captain Jacobs, through an interpreter, rejected the offer, promising only that the lives of any who resisted would be forfeit. As the fire raged and the stockade began to collapse, Armstrong was shot and killed while attempting to rally his men or perhaps to make one last desperate stand.

With their commander dead, their water gone, and the fort ablaze, the remaining 22 men had no choice but to surrender. As the gates were opened or collapsed, the warriors surged in. What followed was a brutal scene. A few of the provincial soldiers were immediately killed, their scalps taken. The rest, including Ensign Turner, were taken captive. The wounded were summarily executed. The fort itself was thoroughly looted, then put to the torch, reducing it to a smoldering ruin.

The Echo of Retaliation: Kittanning

The fall of Fort Granville sent shockwaves across Pennsylvania. It was a stark demonstration of the vulnerability of the frontier and the ferocity of the Native American and French forces. The event ignited public outrage and intensified demands for a more aggressive defense policy.

For Colonel John Armstrong, the news was deeply personal. His brother, Edward, had been killed, and his men captured or massacred. Driven by grief and a thirst for retribution, Armstrong immediately began planning a retaliatory expedition. His target: Kittanning, a major Lenape village on the Allegheny River, a known staging ground for raids and the location where many captives, including some from Fort Granville, were believed to be held.

In September 1756, just weeks after Fort Granville’s fall, Colonel Armstrong led a force of some 300 provincial troops and militia on a daring march through the wilderness. They surprised Kittanning, launching a devastating pre-dawn attack. The ensuing battle was fierce and bloody. The village was burned, many warriors and their families were killed, and some captives were freed. Crucially, Captain Jacobs, the architect of Fort Granville’s destruction, was killed during the raid.

While Kittanning was hailed as a significant victory, boosting colonial morale and demonstrating that Native American villages were not beyond reach, its strategic impact was debated. It did not end the raids, but it did force the Lenape to relocate and rethink their tactics. The fall of Fort Granville and the subsequent Kittanning Expedition became intertwined narratives, twin symbols of the brutal tit-for-tat warfare that defined the Pennsylvania frontier.

A Forgotten Legacy

Today, the exact location of Fort Granville remains a subject of historical debate. No standing structures remain, and archaeological evidence has been elusive, though a historical marker near Lewistown commemorates its tragic story. The land where it once stood has long since returned to agriculture or been developed.

Yet, the story of Fort Granville endures as a powerful, albeit often overlooked, chapter in American history. It represents the desperate struggle of early settlers, the profound injustices inflicted upon Native American peoples, and the harsh realities of colonial warfare. It underscores the immense sacrifices made by those who lived and died on the frontier, their lives caught in the maelstrom of imperial ambition and cultural collision.

The quiet flow of the Juniata River today belies the inferno that once raged on its banks. But for those who remember, the echoes of Fort Granville’s fall – the crackle of flames, the cries of the dying, the desperate pleas for mercy – still resonate, a haunting reminder that even in the most tranquil landscapes, history has a way of leaving its indelible mark. It is a story not just of a fort that burned, but of a frontier that was forged in fire, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape our understanding of courage, conflict, and the enduring spirit of a nation born from struggle.