Where the Wind Whispers Legends: Fort Union, Kiowa, and the Comanches’ Fading Horizon

The American landscape is a vast tapestry woven with threads of history, ambition, and conflict, each strand contributing to a rich fabric of legend. From the misty peaks of the Appalachians to the sun-baked deserts of the Southwest, the very ground seems to hum with untold stories. Yet, few places encapsulate the complex, often tragic, grandeur of the American frontier quite like the windswept ruins of Fort Union in northeastern New Mexico, a silent sentinel that once stood at the pulsating heart of a nation’s expansion, its shadow stretching far across the ancestral lands of the Kiowa and Comanche peoples.

To speak of American legends is to speak of the audacious spirit of westward expansion, the clash of cultures, and the forging of an identity amidst raw, untamed wilderness. It is in this crucible that the stories of Fort Union, the fierce independence of the Kiowa, and the undisputed dominion of the Comanche become not just historical footnotes, but epic narratives of an era defined by struggle, resilience, and an inevitable, devastating transformation.

Fort Union: The Grand Depot of Empire

Imagine a time when the Santa Fe Trail was not merely a historical route, but a bustling highway of commerce, military might, and dreams. At its very nexus, a formidable bastion of federal power rose from the high plains: Fort Union. Established in 1851, this wasn’t just another military outpost; it was the "Grand Depot of the Southwest," a logistical marvel designed to project American authority across a vast and often hostile territory.

From its adobe walls and later, its more permanent stone structures, Fort Union served as the primary supply center for a sprawling network of military posts. Wagons laden with everything from rations and ammunition to uniforms and medical supplies rolled in and out constantly, destined for forts across New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and even parts of Texas. Its strategic importance was underscored during the Civil War, when supplies from Fort Union were instrumental in the Union victory at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, effectively securing the Southwest for the Union cause.

But beyond its strategic and logistical functions, Fort Union represented something far greater: the tangible manifestation of Manifest Destiny, the belief that American expansion across the continent was divinely ordained. It was a symbol of an encroaching world order, one that would inevitably collide with the established ways of life of the Indigenous peoples who had called these lands home for millennia. For many, it was a beacon of progress; for others, a harbinger of doom. The fort, though often geographically distant from the primary battlefields of the "Indian Wars," was nonetheless an engine of those conflicts, fueling the troops and campaigns that would ultimately subdue the great Plains tribes.

The Lords of the Southern Plains: Kiowa and Comanche

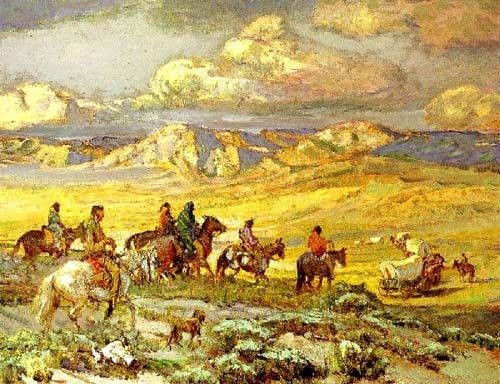

While Fort Union busied itself with the machinery of empire, the Southern Plains to its east and south remained the undisputed domain of two of North America’s most formidable equestrian cultures: the Kiowa and the Comanche. Their legends, rich with tales of daring raids, spiritual quests, and an unbreakable bond with the land and the buffalo, stand in stark contrast to the fort’s stone and steel.

The Comanche, in particular, were known as the "Lords of the Plains." Their vast territory, known as Comancheria, stretched across parts of modern-day Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Masters of horsemanship, they revolutionized warfare and hunting on the plains, their lightning-fast raids and strategic prowess making them a terror to their enemies, both tribal and Euro-American. Their society was decentralized, focused on fierce individual liberty and loyalty to kin, making them incredibly difficult to defeat in a conventional war. "The Comanches were probably the finest light cavalry in the world," noted historian T.R. Fehrenbach, underscoring their military genius. Their lives were inextricably linked to the thundering herds of bison, which provided food, shelter, clothing, and tools, embodying their very existence.

Allied closely with the Comanche were the Kiowa, another nomadic people equally adept on horseback and equally devoted to the buffalo. Though smaller in number, their warriors were renowned for their bravery and their rich ceremonial life, including the Sun Dance, a pivotal annual event that reinforced their spiritual connection to the cosmos and their community. Figures like Satanta, known as the "White Bear," a prominent Kiowa chief and orator, became legendary for their defiance and powerful speeches. "I love to roam over the prairies," Satanta famously declared, "There I feel free and happy; but when I come among the white men, I am unhappy, because I cannot stand still." This sentiment perfectly encapsulated the deep cultural chasm that separated the two worlds.

The Inevitable Collision: Fort Union’s Shadow on Comancheria

The legends of Fort Union and those of the Kiowa and Comanche are not separate tales, but intertwined narratives of a grand, tragic collision. As the American frontier pushed relentlessly westward, fueled by land hunger, the discovery of gold, and the vision of a transcontinental nation, the pressure on the Plains tribes mounted. Fort Union, while not a direct battlefield against these specific tribes in the early years, played a crucial supporting role in the broader military strategy that ultimately led to their subjugation.

It was the supply lines originating from Fort Union that sustained the soldiers of the U.S. Army as they patrolled the plains, protected settlers, and engaged in campaigns designed to confine Indigenous peoples to reservations. The fort’s very existence, its constant flow of men and material, was a stark reminder of the overwhelming force being brought to bear against a way of life that had endured for centuries.

The late 1860s and early 1870s saw the conflict intensify. Treaties, often signed under duress and rarely honored by the U.S. government, failed to stem the tide of settlers or resolve the fundamental clash over land and resources. The buffalo, the very lifeblood of the Kiowa and Comanche, were systematically hunted to near extinction by commercial hunters, a strategy explicitly encouraged by some military leaders to cripple the tribes’ ability to resist. General Philip Sheridan famously remarked, "Let them kill, skin and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance." This ruthless strategy, more than any single battle, sealed the fate of the Plains Indians.

The Red River War of 1874-75 marked the definitive end of independent Kiowa and Comanche power. Exhausted, their food source gone, and relentlessly pursued by the U.S. Army, the tribes were forced onto reservations. Legendary figures like Quanah Parker, the half-Comanche son of a captured white woman, Cynthia Ann Parker, initially led fierce resistance but eventually became a pragmatic leader who guided his people through the painful transition to reservation life. His story, bridging two worlds, is a legend in itself, embodying both the warrior spirit and the difficult path of adaptation.

Echoes of Legends: Memory and Reconciliation

Today, Fort Union stands as a National Monument, its crumbling walls and foundations whispering tales of a bygone era. Visitors can walk among the ruins, imagining the bustling activity, the distant bugle calls, and the weight of history that settled upon this place. But its legends are incomplete without acknowledging the profound impact it had on the Indigenous peoples whose lands it helped to conquer.

The legends of the Kiowa and Comanche, though no longer lived out on the open plains with thundering buffalo herds, endure in their oral traditions, their art, and their vibrant cultural resurgence. They speak of resilience, of a deep spiritual connection to the earth, and of the enduring strength of a people who faced existential threats and survived. These are not merely stories of defeat, but of endurance, identity, and the ongoing struggle for recognition and justice.

The American narrative is often framed as a tale of triumph and progress, but true understanding requires acknowledging the shadows cast by that progress. The legends of Fort Union, the Kiowa, and the Comanche compel us to confront the complexities of our past: the courage and vision of those who built the nation, alongside the tragic dispossession and suffering of those who stood in their path.

In the vast, silent expanse of the Southwest, where the wind still carries the echoes of hoofbeats and human cries, these legends serve as a powerful reminder. They tell us that history is not a simple, linear path, but a mosaic of interconnected stories – some celebrated, others suppressed, but all essential to understanding who we are. To walk the grounds of Fort Union, to learn of the Kiowa and Comanche, is to step into a past where the grand narratives of empire and the fierce defense of ancestral ways clashed, leaving behind a legacy of legends that continue to shape the American identity, urging us to remember, to reflect, and to learn from the rich, often sorrowful, tapestry of our shared heritage.