Where Two Worlds Collided: The Violent Crucible of the Wyoming Plains

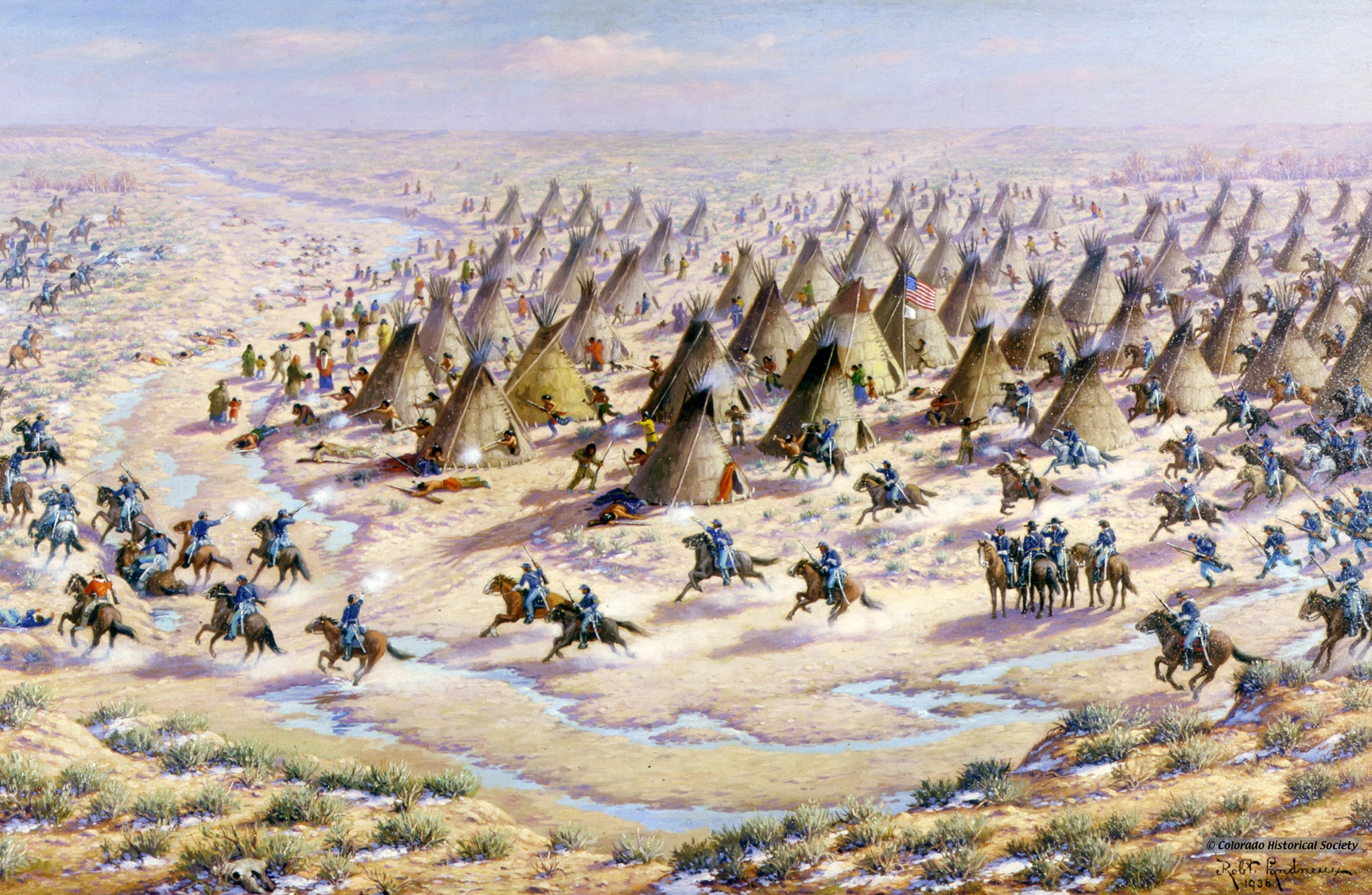

The vast, windswept plains of Wyoming, today a tableau of stark beauty and quiet majesty, once echoed with the thunder of hooves, the crack of rifles, and the desperate cries of a land in contention. In the latter half of the 19th century, this unforgiving frontier became a bloody crucible where the relentless tide of American expansion met the fierce, unyielding resistance of Native American nations. These "Indian attacks," as they were termed by the encroaching Euro-Americans, were not merely isolated skirmishes but critical chapters in a tragic narrative of cultural collision, resource scarcity, and the desperate fight for survival on the High Plains.

To understand the intensity and frequency of these conflicts, one must first grasp the immense forces at play. The United States, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and the insatiable lure of gold and land, pushed westward with relentless vigor. The discovery of gold in Montana in the early 1860s, coupled with the promise of fertile lands for cattle ranching and the eventual construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, transformed Wyoming from a vast, largely unexplored territory into a vital corridor for migration and commerce.

However, these lands were not empty. For millennia, they had been the ancestral domain of powerful Native American tribes, primarily the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, and Arapaho, with the Crow often acting as scouts for the U.S. Army due to long-standing rivalries. These nations were semi-nomadic, their lives intricately woven with the movements of the buffalo, which provided food, shelter, clothing, and spiritual sustenance. The arrival of settlers, miners, and soldiers was not just an inconvenience; it was an existential threat to their way of life, their sacred hunting grounds, and their very identity.

The Bozeman Trail: A Fuse Ignited

A particularly contentious flashpoint was the Bozeman Trail. Carved through the heart of the Powder River Country—prime buffalo hunting grounds and sacred territory for the Lakota and Cheyenne—this shortcut to the Montana goldfields was seen as a direct invasion. Despite the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, which nominally recognized Native land rights, the influx of prospectors and the establishment of U.S. Army forts along the trail, such as Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C.F. Smith, ignited a fierce war of resistance.

Led by the brilliant Oglala Lakota war leader, Red Cloud (Makhpiya Luta), the Native American alliance launched a systematic campaign to halt the encroachment. Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868) is unique in American military history for being a conflict where Native forces largely dictated the terms and ultimately achieved a significant victory. His strategy was one of attrition, cutting off supply lines, harassing travelers, and ambushing military detachments. The "Indian attacks" of this period were not random acts of violence but calculated military maneuvers designed to drive out the invaders.

The Fetterman Fight: A Devastating Ambush

Perhaps the most infamous of these encounters was the Fetterman Fight, which occurred on December 21, 1866, near Fort Phil Kearny. Captain William J. Fetterman, a boastful officer confident in his ability to "whip all the Sioux in the country with eighty men," was ordered to relieve a wood train under attack. Disobeying explicit orders not to pursue the Native warriors beyond Lodge Trail Ridge, Fetterman and his command of 80 men (49 infantry, 27 cavalry, and 2 civilians) rode directly into a meticulously planned ambush.

The decoy party, led by legendary warriors like Crazy Horse, lured Fetterman’s troops over the ridge, where thousands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors lay in wait. The battle was swift and brutal. Within minutes, Fetterman’s entire command was annihilated, every man killed and mutilated in a manner consistent with Native warfare traditions, designed to send a chilling message and prevent the warriors’ spirits from entering the afterlife. The sheer scale of the defeat—81 U.S. soldiers and civilians dead with no known Native casualties—sent shockwaves across the nation.

"Not a man escaped," reported Captain James Powell, who later surveyed the gruesome scene. "The bodies were stripped, scalped, and mutilated in every conceivable manner." This event underscored the deadly effectiveness of Native tactics when facing overconfident and underestimating opponents. For the Native nations, it was a profound victory, a testament to their skill and determination in defending their homeland.

The Wagon Box Fight: Adapting to New Technology

Less than a year later, another engagement near Fort Phil Kearny illustrated the evolving nature of the conflict and the adaptability of both sides. The Wagon Box Fight, on August 2, 1867, saw a small detachment of 32 soldiers and civilians, guarding a logging detail, surrounded by an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. This time, however, the U.S. troops were armed with newly issued breech-loading Springfield rifles, capable of firing much faster than the old muzzle-loaders used at Fetterman.

The soldiers quickly formed a defensive perimeter with 14 overturned wagon boxes, creating makeshift fortifications. The sustained firepower of the breech-loaders inflicted heavy casualties on the charging warriors, who, despite their overwhelming numbers and courage, were unable to breach the improvised fort. The battle, which lasted several hours, resulted in only a handful of U.S. casualties while Native losses were significantly higher, though precise numbers remain debated.

The Wagon Box Fight demonstrated the devastating impact of technological superiority and foreshadowed the eventual shift in the balance of power. It showed that while Native warriors were formidable, they faced an adversary whose industrial might and military technology were rapidly advancing.

The Iron Horse and the Vanishing Buffalo

Beyond direct military engagements, other forces contributed to the escalation and eventual outcome of the "Indian Wars" on the Wyoming Plains. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, pushing through Wyoming, served as both a conduit for settlers and a weapon against Native life. It bisected traditional hunting grounds, brought in thousands of workers, and, perhaps most devastatingly, facilitated the mass slaughter of the buffalo.

Professional buffalo hunters, often encouraged by the U.S. government, systematically decimated the herds. What was once an estimated 30 million buffalo dwindled to a few hundred within decades. For the Plains tribes, this was an attack on their very survival, a deliberate strategy to starve them into submission. "The buffalo is our life," declared one Lakota chief. "Without him, we are nothing." The loss of the buffalo not only eliminated their primary food source but also shattered the spiritual and cultural fabric of their societies.

Broken Promises and the Reservation System

The conflicts on the Wyoming Plains were punctuated by treaties, most notably the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. This treaty, signed after Red Cloud’s War, was a temporary victory for the Native nations. It established the Great Sioux Reservation, encompassing all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and recognized the Powder River Country as unceded Indian territory, where no white settlement or military presence was allowed. Red Cloud himself signed the treaty, believing it would secure peace and his people’s lands.

However, the ink on the treaty was barely dry before its provisions were violated. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills, sacred to the Lakota, in 1874 led to a new gold rush and renewed demands for Native lands. The U.S. government’s subsequent attempts to buy the Black Hills, followed by an ultimatum for the Lakota to report to agencies or be deemed hostile, directly led to the Great Sioux War of 1876-77, which saw further conflict in Wyoming, culminating in events like the Battle of the Little Bighorn (though largely in Montana, it drew warriors and soldiers from the Wyoming theater).

The cycle of broken treaties eroded any trust between Native Americans and the U.S. government, fueling desperation and further resistance. The ultimate consequence was the imposition of the reservation system, confining once-free peoples to small tracts of land, dependent on government rations, and stripped of their traditional way of life.

A Legacy of Contention and Resilience

The "Indian attacks" on the Wyoming Plains were not the actions of simple aggressors but the desperate, often heroic, acts of peoples defending their homes, families, and cultures against an overwhelming tide. From the perspective of the settlers and soldiers, these were dangerous, unpredictable encounters in a harsh wilderness, often driven by fear and a sense of entitlement to the land. For the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, they were battles for survival, for the buffalo, and for the sacred connection to the earth that defined their existence.

Today, the echoes of these conflicts still resonate across Wyoming. Historical markers dot the landscape, commemorating battles and forts, but a deeper understanding requires acknowledging the profound human cost on all sides. The narrative has shifted from one of "savage attacks" to a more nuanced appreciation of Native American resistance, strategic brilliance, and the tragic consequences of unchecked expansion. The plains of Wyoming stand as a powerful reminder of a time when two worlds collided, leaving an indelible mark on the land and the soul of a nation. The resilience of the Native American spirit, though scarred, endures, ensuring that the stories of those who fought for their way of life on the Wyoming frontier will never be truly silenced.