Whispers in the Wind: Unraveling America’s Enduring Superstitions

America, a nation forged in the fires of revolution and built on the promise of rationality and progress, nonetheless harbors a fascinating paradox: a deep, enduring affection for the irrational. From the hallowed halls of professional sports to the quiet comfort of our homes, an intricate tapestry of folklore superstitions continues to weave its way through the fabric of daily life. These aren’t merely quaint historical relics; they are living traditions, whispered warnings, and hopeful charms that reflect a primal human need to understand, influence, and sometimes simply cope with the unpredictable nature of existence.

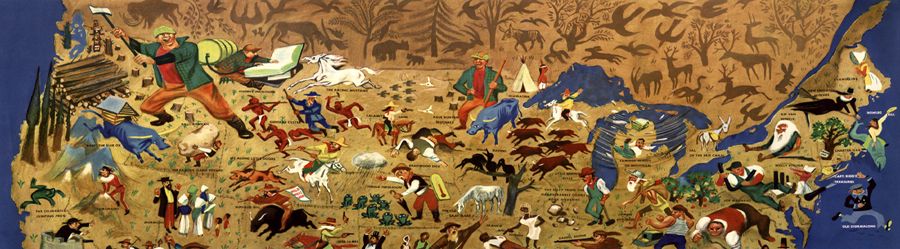

The roots of American superstition are as diverse as the nation itself, a rich stew simmered from European folk traditions, African spiritual practices, and Native American beliefs. Early European settlers brought with them a deep-seated fear of witchcraft, the evil eye, and a host of omens concerning crops, weather, and health. The infamous Salem Witch Trials, a dark chapter in colonial history, stand as a stark reminder of how deeply such beliefs could grip a community, transforming suspicion into deadly conviction. Simultaneously, enslaved Africans brought their own complex systems of belief, including conjure, hoodoo, and a profound understanding of natural remedies and spiritual protections, which subtly (and sometimes overtly) blended with European practices. Native American tribes, with their deep reverence for nature and understanding of spiritual interconnectedness, contributed their own rich lore concerning animal omens, sacred places, and the balance of the universe. This cultural melting pot ensured that no single superstitious tradition would dominate, but rather a hybrid, uniquely American blend would emerge.

Many of our most common superstitions are direct descendants of these ancestral influences. Take, for instance, the ubiquitous fear of black cats. This aversion stems largely from medieval European folklore, where black cats were associated with witches and the devil. They were often believed to be witches’ familiars or even witches themselves in disguise. While modern society largely dismisses such notions, the instinct to pause or change direction when a black cat crosses one’s path persists, a silent nod to centuries of ingrained fear.

Similarly, breaking a mirror and incurring seven years of bad luck is a superstition with ancient Roman origins. The Romans believed that a person’s reflection was a glimpse into their soul, and that mirrors had the power to draw out or absorb part of that soul. A broken mirror, therefore, signified a damaged or shattered soul. The "seven years" aspect is thought to relate to the Roman belief that life renewed itself every seven years, meaning the soul would take that long to fully regenerate and shake off the ill effects.

The seemingly innocuous act of walking under a ladder is another widespread taboo. Its origins are multifaceted. One theory traces it back to ancient Egypt, where a leaning ladder formed a triangle, a sacred shape representing the Holy Trinity. To pass through this triangle was seen as a desecration. Another, more practical explanation, suggests that ladders were historically associated with gallows, making walking under one an omen of death or bad fortune. A third, simpler reason is the sheer danger of having something fall on your head. Regardless of its genesis, the instinct to avoid that triangular space remains strong for many.

Not all superstitions are about avoiding misfortune; many are designed to invite good luck. The four-leaf clover, a rare mutation of the common three-leaf variety, has been a symbol of good fortune since ancient Celtic times. Each leaf is said to represent a different quality: the first for hope, the second for faith, the third for love, and the fourth for luck. Finding one is still considered a stroke of extraordinary fortune, a small, green talisman against the world’s vagaries.

Perhaps even more potent as a good luck charm is the rabbit’s foot. This belief is deeply rooted in various cultures, including ancient Celtic traditions, but it gained particular prominence in America through African American conjure and Hoodoo practices. For these traditions, the left hind foot of a rabbit, especially one killed in a cemetery or under specific lunar conditions, was believed to possess powerful protective and luck-bringing qualities. It was often carried as an amulet, offering protection from evil and attracting good fortune, particularly in gambling or matters of the heart.

Beyond these well-known examples, American superstitions permeate countless aspects of daily life. Consider the simple act of spilling salt. Rather than merely an inconvenience, it’s often seen as an invitation for bad luck or even the devil. The antidote? Quickly toss a pinch of the spilled salt over your left shoulder, aiming to blind any evil spirits lurking there. This tradition is famously depicted in Leonardo da Vinci’s "The Last Supper," where Judas Iscariot is shown having spilled the salt, foreshadowing his betrayal.

The human body itself is a canvas for various omens. An itchy palm often signifies incoming money (right palm to receive, left to pay out). Sneezing can be a sign that someone is thinking of you, or that a lie has just been told. A ringing in the ears might indicate someone is talking about you, with the specific ear often dictating whether the conversation is positive or negative. These body-based superstitions speak to a desire to interpret our own physical experiences as messages from an unseen world.

In the realm of love and marriage, superstitions abound, offering a blend of hope and playful anxiety. The bride’s bouquet toss to her single friends, the belief that rain on your wedding day signifies good luck and fertility, or the adherence to the "something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue" mantra – all are practices steeped in tradition, designed to ensure a happy and prosperous union. Even the seemingly innocent act of a groom seeing his bride before the ceremony is widely considered bad luck, a vestige of arranged marriages where the couple might not have met until the altar.

Seasonal and agricultural superstitions also hold sway, often reflecting practical observations wrapped in folklore. Groundhog Day, celebrated every February 2nd, is perhaps the most famous. If Punxsutawney Phil (or his local equivalent) sees his shadow, six more weeks of winter are predicted; if not, an early spring. This tradition, brought by German immigrants, reflects ancient European beliefs about predicting spring based on animal behavior, particularly badgers or bears. Similarly, the saying "Red sky at night, sailor’s delight; red sky in morning, sailor’s warning" is a meteorological observation passed down through generations, still holding practical (and superstitious) weight for those who work the land or sea.

But why do these beliefs persist in an age of science and reason? The answer lies in the deeply human need for control, comfort, and meaning. Superstitions offer a sense of agency in an often-unpredictable world. When faced with uncertainty – be it a job interview, a sporting event, or a health scare – a ritualistic act, however small, can provide a psychological anchor. It creates an illusion of control, a feeling that one can influence outcomes through a specific action or avoidance.

"Superstitions are often a way for humans to impose order on a chaotic world," notes Dr. Sarah Miller, a folklorist specializing in American traditions. "They give us a framework, however illogical, to understand cause and effect, and they provide comfort in times of anxiety. It’s less about actual belief in magic, and more about the psychological benefit of having a ritual."

Moreover, superstitions are powerful carriers of cultural identity and social cohesion. They are shared narratives, inside jokes, and common practices that bind communities. Passing them down from generation to generation reinforces familial bonds and cultural heritage. They are part of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

In modern America, superstitions have also found new expressions. Sports superstitions are legendary, with athletes often adhering to rigid pre-game rituals, lucky socks, or avoidance of certain phrases, believing these actions directly influence their performance. Fans, too, participate, wearing specific jerseys, sitting in designated spots, or performing cheers in a particular order. These behaviors highlight the high stakes and emotional investment involved, where any perceived edge, however irrational, is embraced.

Beyond sports, the casual "knock on wood" after making a positive statement, the avoidance of the number 13 (leading to "12A" floor numbers in some buildings), or the ironic yet still practiced "crossing fingers" for good luck, demonstrate how deeply ingrained these behaviors remain. Even in a secular, scientifically advanced society, the urge to acknowledge the unseen forces of luck and fate continues.

Ultimately, American folklore superstitions are more than just quaint relics of a bygone era. They are vibrant, evolving aspects of our cultural landscape, a testament to humanity’s enduring quest for meaning, control, and connection. They remind us that even in the most rational of societies, there remains a primal, mystical thread connecting us to our past, whispering cautions and promises in the wind, inviting us to believe, just a little, in the magic that lies beyond what we can fully explain. They are the invisible threads that weave through our collective consciousness, a subtle yet powerful reminder that even in the land of the free and the home of the brave, we still occasionally cross our fingers and knock on wood.