Whispers on the Panhandle Wind: Exploring Hutchinson County’s Ghost Towns

The Texas Panhandle is a land of vast horizons, where the sky seems to stretch into infinity and the wind hums a ceaseless, ancient tune. It’s a landscape that tells tales of ambition and failure, of dreams built on shifting sands and fortunes blown away by the very elements that shaped them. Nowhere are these stories more poignantly etched than in the forgotten corners of Hutchinson County, a region that once pulsed with the frenetic energy of an oil boom, only to see many of its nascent towns fade into the silent embrace of the prairie.

These aren’t just abandoned ruins; they are open-air museums, vital chapters in the larger narrative of Texas, reflecting the relentless boom-and-bust cycles, the intoxicating allure of natural resources, and the harsh realities of a frontier that demanded both resilience and a touch of madness. To explore Hutchinson County’s ghost towns is to walk through the echoes of a past where fortunes were made and lost overnight, where communities sprang from nothing and vanished just as quickly, leaving behind only the spectral remnants of their brief, vibrant lives.

A Land Shaped by Ancient Currents and Modern Dreams

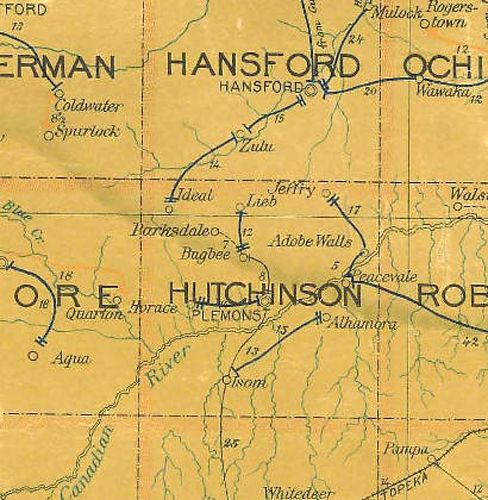

Before the roar of oil derricks, Hutchinson County was a land defined by the Canadian River and the vast, untamed prairie. It was the ancestral hunting grounds of indigenous peoples, notably the Comanche, whose nomadic lifestyle was perfectly suited to its expansive plains. Later, in the 19th century, it became a crucial part of the legendary cattle trails, with sprawling ranches like the LX and the Turkey Track dominating the landscape. Iconic historical events, such as the two Battles of Adobe Walls (1864 and 1874), underscore the region’s early significance as a crossroads of cultures and conflicts. These early skirmishes, though not leading to permanent settlements, set a precedent for the rugged individualism and often violent struggles that would characterize the region’s later development.

The first attempts at establishing permanent communities were modest, largely agricultural or ranching outposts. Towns like Plemons, founded in 1901, emerged as early hubs, serving the scattered ranching families and acting as the county seat. Life was hard, dictated by the unpredictable weather and the vast distances between neighbors. But beneath the stoic surface of the Panhandle lay a hidden promise, a liquid treasure that would utterly transform its destiny: oil.

The Black Gold Rush: When the Prairie Trembled

The early 20th century brought the seismic shift. In 1921, the discovery of oil in the Panhandle, specifically the Panhandle Field, ignited a frenzy that would reshape Hutchinson County forever. The quiet prairie exploded into a cacophony of sound – the clang of steel, the hiss of steam, the shouts of wildcatters, and the roar of newly drilled wells. "Black gold" became the mantra, and men and women from all corners of the nation flocked to the Panhandle, drawn by the irresistible siren song of instant wealth.

Suddenly, small, dusty settlements were overwhelmed, and new towns materialized almost overnight, often without planning or adequate infrastructure. Borger, established in 1926 by the infamous "Booger Red" Phillips, became the epicenter of this boom, a legendary "Derrick City" that grew from zero to over 10,000 residents in a matter of months. Its early days were marked by lawlessness, gambling, prostitution, and a general disregard for prohibition, earning it a reputation as one of the wildest towns in Texas. It’s said that even Al Capone eyed Borger as a potential base for his illicit operations.

But Borger was not alone. Many smaller satellite towns, company camps, and speculative settlements also sprang up, hoping to catch the overflow or tap into new discoveries. These were the true boomtowns, designed for immediate exploitation rather than long-term sustainability. They were built quickly, often with makeshift materials, their existence inextricably linked to the ebb and flow of crude oil from the ground beneath them.

The Inevitable Bust: Dreams Turned to Dust

The frantic pace of the oil boom, however, was inherently unsustainable. Several factors conspired to turn these bustling communities into the silent specters we see today:

- Resource Depletion: As oil wells matured and production declined, the economic engine that fueled these towns sputtered. The jobs vanished, and with them, the people.

- Economic Downturns: The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, dealt a severe blow. Demand for oil plummeted, prices crashed, and investment dried up. Many who had flocked to the Panhandle found themselves jobless and destitute.

- The Dust Bowl: Beginning in the early 1930s, a series of devastating droughts and poor farming practices turned the fertile topsoil into a choking, black blizzard. The Dust Bowl was an environmental catastrophe that drove countless families from the region, leaving behind homes and businesses buried under drifts of sand. Even those not directly involved in agriculture were affected by the sheer impossibility of life in such conditions.

- Improved Infrastructure: As roads and transportation improved, smaller, isolated towns became less necessary. People could more easily travel to larger centers like Borger or Amarillo for goods and services, draining the economic lifeblood from the smaller communities.

- Company Town Vulnerability: Many settlements were essentially "company towns," built and managed by oil companies for their workers. When the company moved operations or scaled back, the town often dissolved with it.

These combined forces proved too powerful for many of Hutchinson County’s fledgling communities. The roar of the derricks faded, replaced by the mournful whistle of the Panhandle wind, sweeping through empty storefronts and rattling the windows of abandoned homes.

Echoes in the Emptiness: Case Studies of Forgotten Towns

While Borger endured, adapting and diversifying, many of its hopeful neighbors did not. Their stories are a testament to the impermanence of human endeavor in the face of economic and environmental forces.

Plemons: Once the proud county seat, Plemons’ fate was sealed not by oil depletion, but by political maneuvering and changing demographics. Established in 1901, it was the administrative heart of the county for over two decades, boasting a courthouse, a newspaper, a bank, and several general stores. Its peak population hovered around 300 hardy souls. However, the oil boom shifted the population balance dramatically towards the eastern part of the county, particularly Borger. In 1926, a contentious election moved the county seat to Stinnett, a more centrally located town that could better serve the burgeoning oil communities. With the loss of its governmental function, Plemons began a slow, inexorable decline. Today, little remains beyond a few crumbling foundations, a forgotten cemetery, and the pervasive silence, a stark reminder of how swiftly civic pride can be eroded by circumstance. Historian Dr. Eleanor Vance notes, "Plemons is a poignant reminder of how swiftly fortunes can turn, not just for individuals, but for entire communities. It shows that even a county seat isn’t immune to the forces of change."

Whittenburg: A classic example of an oil boom company town, Whittenburg sprang to life in 1926 with the discovery of the Whittenburg Field. Named for rancher and oilman J.L. Whittenburg, it was primarily a camp for Gulf Production Company workers. At its peak, it housed over a thousand residents, complete with a school, commissary, and a handful of businesses catering to the transient population. Life here was rough and ready, focused entirely on the extraction of oil. When the oil production began to wane in the 1940s and 50s, Gulf Production gradually dismantled its operations. The houses were moved, the school closed, and the stores shuttered. What remains today are scattered concrete pads, a few rusty pipes, and the overwhelming sense of absence, where once a thriving, if temporary, community bustled with life. The very ground, now scarred by forgotten roads, seems to whisper the names of those who once lived and worked there.

Courson and Dial: These were even more fleeting settlements, perhaps never reaching "town" status but serving as vital, albeit temporary, oil camps or rail stops. Courson, for instance, was established around 1926-1927, tied to a rail spur and the local oil fields. It had a post office for a few years, a general store, and a handful of houses. Dial was similarly transient. Such places often faded as quickly as they appeared, leaving behind only historical markers or obscure mentions in old county records. Their stories are less about dramatic decline and more about the inherent fragility of communities built on the shifting sands of a single resource. As local Panhandle writer, Sarah Jensen, observes, "These micro-towns, barely a blip on the map, tell us just as much as the larger ones. They are the ultimate testament to the ‘here today, gone tomorrow’ ethos of the boom-and-bust cycle."

The Enduring Legacy: More Than Just Ruins

Today, the ghost towns of Hutchinson County are not simply ruins; they are integral parts of the landscape, imbued with a quiet power that transcends their physical decay. They serve several crucial functions:

- Historical Markers: They are tangible links to a pivotal era in Texas history, demonstrating the raw energy and often chaotic nature of the oil booms that shaped the state’s economy and identity.

- Lessons in Sustainability: They offer stark lessons about the dangers of single-resource economies and the importance of diversification, a lesson Hutchinson County itself has learned, now boasting significant wind energy production alongside its still-active oil and gas industry and traditional agriculture.

- Cultural Heritage: For local historians, photographers, and "ghost town hunters," these sites are treasures, offering insights into early 20th-century frontier life, architecture, and the human spirit’s resilience. They are places of reflection, where the past feels palpably close.

- The Allure of the Unknown: For many, the mystery and desolation of these places hold a unique appeal, drawing visitors who seek to connect with the echoes of lives long past, to imagine the bustling streets and hear the phantom laughter and struggles carried on the wind.

As the sun sets over the Panhandle, casting long shadows across the crumbling foundations and forgotten fields, the ghost towns of Hutchinson County stand as silent sentinels. They are not merely empty spaces, but storytellers, whispering tales of ambition, struggle, and the relentless march of time. They remind us that even in the vast, seemingly unchanging landscape of Texas, nothing truly stays the same. The wind, which once carried the scent of crude oil and the shouts of prospectors, now carries only the dust of history, a profound and beautiful silence that speaks volumes about the dreams that once bloomed and withered on the Panhandle plains.