Voices of Resilience: Charting the Legacy of Native American Activism

In the vast tapestry of American history, the struggle for Indigenous rights, sovereignty, and cultural preservation stands as one of its most enduring and often overlooked narratives. For centuries, Native American peoples have resisted assimilation, fought for their lands, and championed their unique identities in the face of immense pressure. From the forceful confrontations of the Red Power movement to the nuanced political advocacy of today, a lineage of courageous activists has emerged, their voices echoing the resilience and determination of their ancestors.

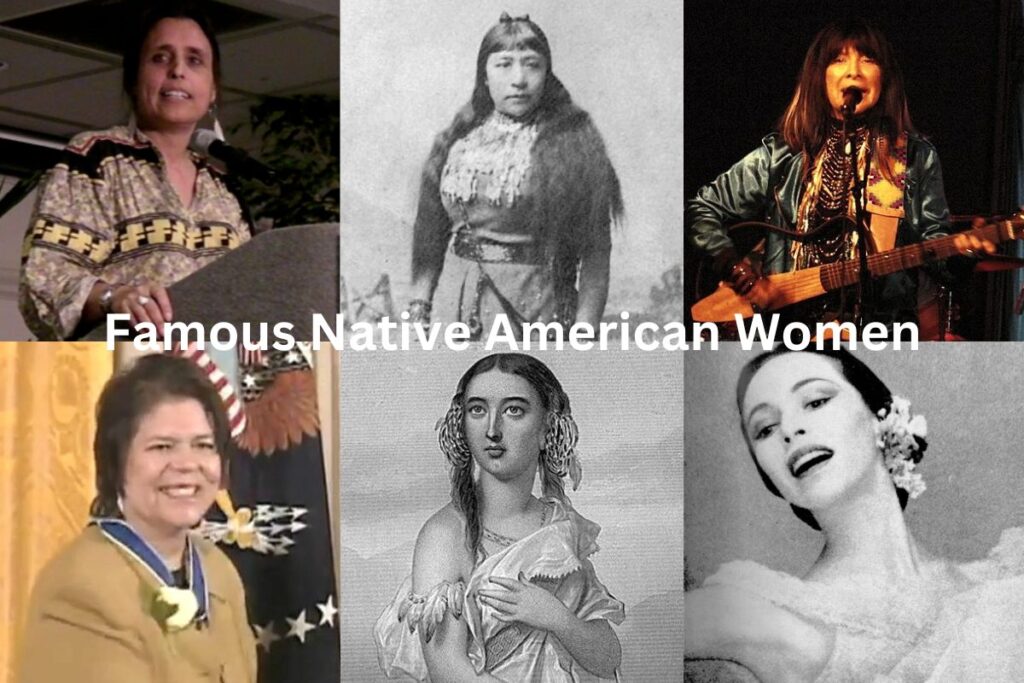

This article delves into the lives and legacies of some of the most famous Native American activists, exploring their contributions, the challenges they faced, and the profound impact they’ve had on both Indigenous communities and the broader American consciousness. Their stories are not just historical footnotes; they are living testaments to an ongoing fight for justice and recognition.

The Genesis of Modern Activism: From Alcatraz to Wounded Knee

While resistance to colonial encroachment dates back centuries, the mid-20th century saw the rise of organized, national movements demanding self-determination. The 1960s and 70s, fueled by the broader Civil Rights Movement, ignited what became known as the "Red Power" era. Frustrated by broken treaties, poverty, and the federal government’s disastrous "termination" policies, a new generation of activists emerged, ready to challenge the status quo with bold, direct action.

One of the most iconic events was the 1969 Occupation of Alcatraz Island. Led by the group Indians of All Tribes, primarily students and urban Native Americans, the occupation lasted 19 months. They claimed the island by right of discovery, citing an 1868 treaty that allowed Native Americans to reclaim abandoned federal land. Though the occupation eventually ended without permanent land transfer, it galvanized Native American communities, drawing unprecedented media attention to Indigenous issues and inspiring a wave of similar actions across the country. It was a powerful declaration: "We are still here."

Emerging from this fervent period was the American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968 in Minneapolis by Dennis Banks, George Mitchell, and Clyde Bellecourt. AIM quickly became the most prominent and, at times, controversial Native American rights organization. Initially focused on addressing police brutality and systemic discrimination against urban Indigenous populations, AIM rapidly expanded its scope to include treaty rights, sovereignty, and cultural revitalization.

Russell Means, an Oglala Lakota, quickly rose as one of AIM’s most recognizable and fiery leaders. With his long braids, cowboy hat, and defiant rhetoric, Means became the face of a new, unapologetic Indigenous identity. He famously declared, "We are not a conquered people," encapsulating the spirit of resistance that defined AIM. Means was a central figure in many of AIM’s high-profile actions, including the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties march on Washington D.C., which culminated in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) headquarters.

The most intense and symbolic confrontation occurred in 1973 at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. AIM leaders, including Dennis Banks and Russell Means, along with members of the Oglala Lakota, occupied the historic site – the location of the 1890 massacre of Lakota people by U.S. troops. The 71-day standoff with federal agents brought the plight of Native Americans to global attention. It highlighted the deep-seated grievances over treaty violations and the dire conditions on reservations. While the siege ended in a negotiated settlement, it left a lasting legacy of both inspiration and deep-seated trauma, particularly with the subsequent legal battles and the controversial imprisonment of AIM member Leonard Peltier, whose case remains a symbol of injustice for many Indigenous people worldwide.

Beyond Confrontation: The Rise of Political & Policy Advocacy

While AIM’s confrontational tactics were crucial for breaking the silence surrounding Indigenous issues, the movement also paved the way for more nuanced forms of activism focused on political power, legal reform, and self-governance.

/RussellMeans-584747753df78c0230e4cc31.jpg)

Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee Nation) stands as a monumental figure in this evolution. In 1985, she became the first woman to be elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest tribal governments in the United States. Mankiller’s leadership marked a turning point, demonstrating that Indigenous sovereignty could be exercised through effective governance and community development, not just protest. She focused on improving healthcare, education, and housing for her people, famously stating, "The Cherokee Nation is a reflection of the people’s resilience." Her approach emphasized self-help and nation-building, inspiring countless Indigenous women to pursue leadership roles.

Another pivotal figure in policy change was Ada Deer (Menominee). As a key organizer in the movement to reverse the federal government’s "termination" policy – which sought to dismantle tribal governments and assimilate Native Americans – Deer achieved a historic victory when the Menominee Tribe was federally recognized again in 1973. Later, she became the first Native American woman to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1993, working within the very system she once fought to change. Her career exemplified the shift towards legislative and administrative advocacy.

LaDonna Harris (Comanche) has been a tireless advocate for Indigenous rights since the 1960s, working across political divides. She founded Americans for Indian Opportunity (AIO) in 1970, which has been instrumental in promoting tribal self-determination and strengthening Indigenous leadership. Harris ran for Vice President of the United States in 1980 on the Citizens Party ticket, becoming the first Native American woman to seek such a high office. Her work has consistently emphasized the importance of Indigenous knowledge and values in addressing contemporary global challenges.

More recently, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) made history in 2021 by becoming the first Native American Cabinet Secretary, serving as the Secretary of the Interior. Her appointment signifies a profound shift, placing an Indigenous woman at the helm of the very department that has historically managed – and often mismanaged – Native American lands and affairs. Haaland’s presence in such a powerful position offers a direct voice for Indigenous communities at the highest levels of government, promising a new era of consultation and respect.

Guardians of the Earth: Environmental & Land Activism

For Native peoples, land is not merely property; it is a sacred relative, intrinsically linked to identity, culture, and survival. This deep connection has made environmental protection a cornerstone of Indigenous activism.

Winona LaDuke (Anishinaabeg/Ojibwe) is a leading voice in environmental justice, Indigenous rights, and sustainable development. A two-time Green Party Vice Presidential candidate, LaDuke founded Honor the Earth, an organization dedicated to raising awareness and financial support for Indigenous environmental struggles. She has been at the forefront of numerous campaigns against fossil fuel pipelines, most notably the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests at Standing Rock, where she was a prominent figure alongside thousands of water protectors. Her mantra, "Water is life," resonates deeply with the global environmental movement.

Another giant in this field was Billy Frank Jr. (Nisqually), a legendary fishing rights activist from the Pacific Northwest. For decades, Frank bravely defied state laws that infringed upon his tribe’s treaty-guaranteed fishing rights. His relentless "fish-ins" and arrests ultimately led to the landmark 1974 Boldt Decision, which affirmed treaty rights and allocated half of the harvestable salmon to tribes in Washington State. Frank’s life work was a testament to the enduring power of treaty rights and the courage required to defend them.

Cultural Preservation and Artistic Expression as Activism

Activism also takes the form of preserving and celebrating Indigenous cultures, languages, and artistic traditions, often seen as acts of resistance against historical attempts at cultural erasure.

Joy Harjo (Muscogee (Creek) Nation) embodies this form of activism through her groundbreaking poetry. As the first Native American U.S. Poet Laureate, Harjo uses her powerful voice to explore themes of Indigenous identity, history, and resilience, bringing Native narratives to a wider audience. Her work is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and the vital role of art in maintaining cultural continuity.

John Trudell (Santee Dakota), initially a prominent AIM spokesperson, transitioned into a powerful poet, musician, and activist. After a devastating fire, believed to be arson, killed his wife and children, Trudell dedicated his life to using art as a vehicle for social change. His spoken-word poetry and music, often raw and politically charged, offered profound reflections on Indigenous sovereignty, environmental destruction, and spiritual resilience. He famously said, "We are not a people of the past, we are a people of the future."

Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne & Hodulgee Muscogee) is a lifelong advocate for Native American rights, cultural preservation, and religious freedom. She was instrumental in the passage of significant legislation, including the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and the National Museum of the American Indian Act. Harjo is also well-known for her tireless fight against the use of Native American mascots in sports, notably leading the legal battle against the former Washington NFL team’s name, which she called a "dictionary-defined racial slur." Her work highlights the ongoing struggle against cultural appropriation and for respectful representation.

The Ongoing Journey: New Challenges, New Voices

Today, Native American activism continues to evolve, addressing contemporary challenges with renewed vigor. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement has gained significant momentum, drawing attention to the disproportionately high rates of violence against Indigenous women and girls in North America. Activists, often led by grassroots organizers and family members, are demanding justice, better data collection, and systemic change.

Youth activists are increasingly using digital platforms and social media to organize, educate, and amplify Indigenous voices globally. From pipeline protests to advocating for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a new generation is building on the foundations laid by their predecessors, demonstrating the enduring strength and adaptability of Native American activism.

Conclusion

The history of Native American activism is a testament to unwavering resilience, a profound connection to land and culture, and an unyielding pursuit of justice. From the bold actions of the Red Power era to the nuanced policy work and cultural revitalization efforts of today, iconic figures like Russell Means, Wilma Mankiller, Winona LaDuke, and Deb Haaland have left indelible marks.

Their struggles and triumphs remind us that the fight for sovereignty, self-determination, and human rights is an ongoing journey. These activists, past and present, are not merely historical figures; they are living examples of how courage, community, and an unwavering spirit can challenge oppression and shape a more just future for all. Their voices continue to call for a true understanding and respect for the First Peoples of this land, ensuring that their legacy of resistance and resilience endures for generations to come.