Beyond the Stereotype: Unveiling the Masterful World of Native American Artists

For too long, the narrative surrounding Native American art has been confined to a narrow, often romanticized, or anthropological lens. Seen primarily as artifacts of a bygone era or curiosities of craft, the profound contributions of Indigenous artists to the broader canvas of American and global art have been persistently underestimated or overlooked. Yet, from the ancient petroglyphs etched into canyon walls to the vibrant contemporary installations challenging modern perceptions, Native American artists have consistently created powerful, innovative, and deeply resonant works that speak to identity, sovereignty, land, and the enduring human spirit.

This article aims to peel back the layers of misconception, celebrating a diverse constellation of famous Native American artists who have not only preserved rich cultural legacies but have also fearlessly pushed boundaries, redefined artistic canons, and offered critical perspectives on history, politics, and the future. Their work, often infused with ancestral knowledge and personal narratives, is a testament to resilience, creativity, and an unwavering commitment to truth.

The Pioneers: Bridging Worlds and Breaking Ground

The early 20th century saw a pivotal shift as Native artists began to transition from traditional forms, often created for community use or trade, into the Western "fine art" world. This transition was fraught with challenges, including stereotypes and market pressures to conform to romanticized notions of "Indian art." Yet, trailblazers emerged, laying the groundwork for future generations.

One of the most iconic figures of this era is Maria Martinez (Maria Poveka Montoya, San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1887-1980). Though her medium was pottery, her impact transcended craft, elevating Pueblo pottery to an art form recognized worldwide. Famous for her black-on-black ware, developed with her husband Julian, Maria revived traditional techniques, achieving a matte and polished surface contrast that captivated collectors. Her dedication not only brought economic prosperity to her community but also instilled a renewed sense of pride in Pueblo artistic heritage. Her work wasn’t just beautiful; it was a powerful assertion of cultural continuity. As she famously said, "My hands are just tools. The clay is from the earth, and the fire is from the sky. It is a gift."

Another pivotal figure was Oscar Howe (Yankton Dakota, 1915-1983). Howe was a fierce advocate for artistic freedom, challenging the restrictive "flat style" often imposed on Native artists by early art institutions. His abstract, dynamic paintings, which incorporated Dakota cosmology and modern art principles, were revolutionary. In 1958, after his painting "Dakota Emergency" was rejected by the Philbrook Indian Art Annual for not being "Indian" enough, Howe wrote a blistering letter that became a manifesto for Native American art: "Are we to be held back forever with the crushing weight of a dead past? …There is much more to Indian art than pretty patterns and pretty colors. Indian art can be a living art, it can be a great art, but it must be free." This defiant stance opened doors for future generations to explore diverse artistic expressions without being confined to narrow expectations.

The Mid-Century Mavericks: Challenging Perceptions

The mid-20th century witnessed the rise of artists who directly confronted and dismantled prevailing stereotypes, often emerging from institutions like the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, which fostered a more experimental and contemporary approach to Native art.

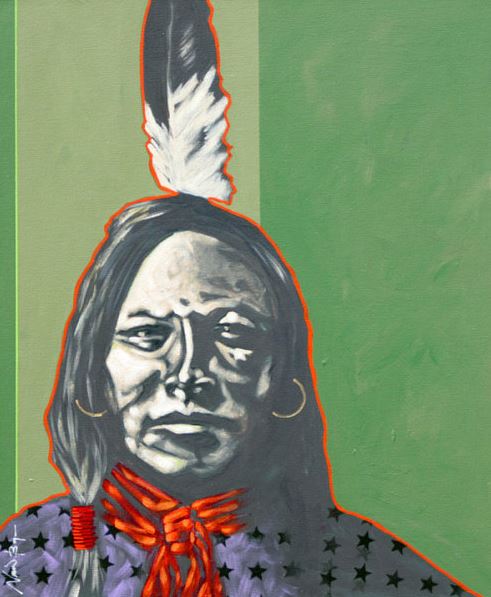

Fritz Scholder (Luiseño, 1937-2005) stands as one of the most influential and controversial figures of this period. A student of Oscar Howe, Scholder famously declared that he would "never paint Indians." Yet, he became renowned for his powerful, often unsettling, depictions of Native Americans. His "Indian Series" (1967-1980) portrayed Indigenous people not as noble savages or romanticized figures, but as complex individuals grappling with alcoholism, alienation, and the absurdities of reservation life. Using vibrant, non-traditional colors and a bold, expressionistic style, Scholder shattered clichés. He famously stated, "I am not an Indian artist. I am an artist who happens to be Indian." This declaration encapsulated his desire to be judged by the universal standards of art, rather than by his ethnicity, while simultaneously using his heritage as a powerful lens for social commentary.

A contemporary of Scholder, though tragically short-lived, was T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo, 1946-1978). Cannon’s vibrant, highly detailed paintings offered a counterpoint to Scholder’s darker themes, often depicting Native figures in unexpected, anachronistic settings, blending traditional attire with modern elements. His work was characterized by rich color palettes and a unique blend of Pop Art influences with Indigenous storytelling. Despite his untimely death at 31, Cannon’s work profoundly impacted the contemporary Native art movement, showcasing a more celebratory yet still critical view of Indigenous identity.

In sculpture, Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache, 1914-1994) achieved international acclaim. Descended from a lineage that included Geronimo, Houser’s work evolved from realistic carvings to monumental, abstract forms in stone and bronze, yet always retaining a connection to his Apache heritage and the natural world. His sculptures, often characterized by flowing lines and a sense of powerful stillness, evoke universal human emotions and a deep respect for the earth. Pieces like "Spirit of the Wind" embody a grace and dignity that transcend cultural boundaries. Houser’s influence as an artist and a mentor at IAIA was immense, shaping generations of Native sculptors. He once reflected, "My work is very important to me because I believe in the things I’m doing. I feel that what I am doing is very important to my people, and to the world."

Contemporary Voices: Diverse Forms, Urgent Messages

Today’s Native American artists continue to build upon these legacies, pushing the boundaries of media, subject matter, and conceptual depth. Their work often grapples with issues of colonialism, environmentalism, identity, sovereignty, and the ongoing process of decolonization.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish/Kootenai/Métis, b. 1940) is a formidable force in contemporary art. Her large-scale mixed-media paintings and installations are rich with symbolism, addressing environmental concerns, corporate greed, governmental policies, and the complex realities of Native life. She often incorporates maps, newspaper clippings, and commercial logos, layering them with abstract forms and Indigenous motifs. Her "Trade Canoe" series, for example, uses the iconic vessel to comment on historical and contemporary trade, cultural exchange, and exploitation. Smith’s art is unapologetically political, serving as a powerful tool for social commentary and activism. She famously stated, "Art is a weapon. It’s a tool. It’s a way of life."

Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee Nation, b. 1935) is celebrated for her powerful diptychs, which often juxtapose abstract or minimalist landscapes with more detailed, expressive depictions of the land. Her work explores memory, history, and the profound spiritual connection Native peoples have to the earth. WalkingStick’s paintings often evoke a sense of deep contemplation, inviting viewers to consider the layers of meaning embedded within the landscape – geological, historical, and personal. Her dedication to exploring the dualities of experience makes her a unique voice in contemporary art.

George Morrison (Grand Portage Band of Chippewa, 1919-2000), a leading figure in Abstract Expressionism, was renowned for his large-scale paintings and wood collages that evoked the landscapes of his Ojibwe homeland. While his work was abstract, it was deeply rooted in the natural world and his Indigenous heritage, challenging the notion that Native art must be purely figurative or narrative. Morrison seamlessly blended modernist aesthetics with an Indigenous sensibility, creating art that was both universal and deeply personal.

Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo, b. 1962) is a masterful sculptor working primarily in clay. Her life-sized and smaller figurative sculptures often depict expressive, humorous, and deeply human characters grappling with contemporary issues, while also reflecting Pueblo traditions and spiritual beliefs. Swentzell’s work is characterized by its raw emotional honesty and its ability to connect with viewers on a visceral level, exploring themes of communication, community, and the human condition.

Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke (Crow), b. 1983) uses photography, performance, and mixed media to challenge historical inaccuracies and romanticized portrayals of Native Americans, particularly within ethnographic archives. Her work often recontextualizes historical images, infusing them with humor, contemporary references, and a distinctly Indigenous female gaze. By inserting herself into historical photographs or creating elaborate dioramas, Red Star reclaims narratives, offering a nuanced and often playful critique of colonialism and representation.

The Enduring Legacy

The artists mentioned here represent just a fraction of the immense talent within Native American communities. Their collective work demonstrates an extraordinary range of styles, mediums, and conceptual approaches. What unites them, however, is a profound commitment to storytelling, cultural preservation, and a relentless pursuit of truth.

Their art serves multiple vital functions: it educates audiences about Indigenous histories and contemporary realities; it challenges stereotypes and demands recognition; and it provides a powerful platform for self-determination and cultural revitalization. From the quiet resilience of Maria Martinez’s pottery to the bold defiance of Oscar Howe and Fritz Scholder, and the critical insights of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Wendy Red Star, these artists have not only shaped the landscape of American art but have also contributed immeasurably to a global conversation about identity, justice, and the power of creative expression.

In a world increasingly seeking authenticity and diverse perspectives, the voices of Native American artists are more vital than ever. They remind us that art is not merely decoration but a living, breathing force capable of challenging, healing, and transforming. Their legacies are not confined to museums or galleries; they resonate in the ongoing struggle for sovereignty, the preservation of ancestral lands, and the vibrant continuation of Indigenous cultures across the continent. To truly appreciate American art is to recognize and celebrate the indispensable contributions of its first artists – the brilliant, diverse, and ever-evolving tapestry woven by Native American hands and minds.