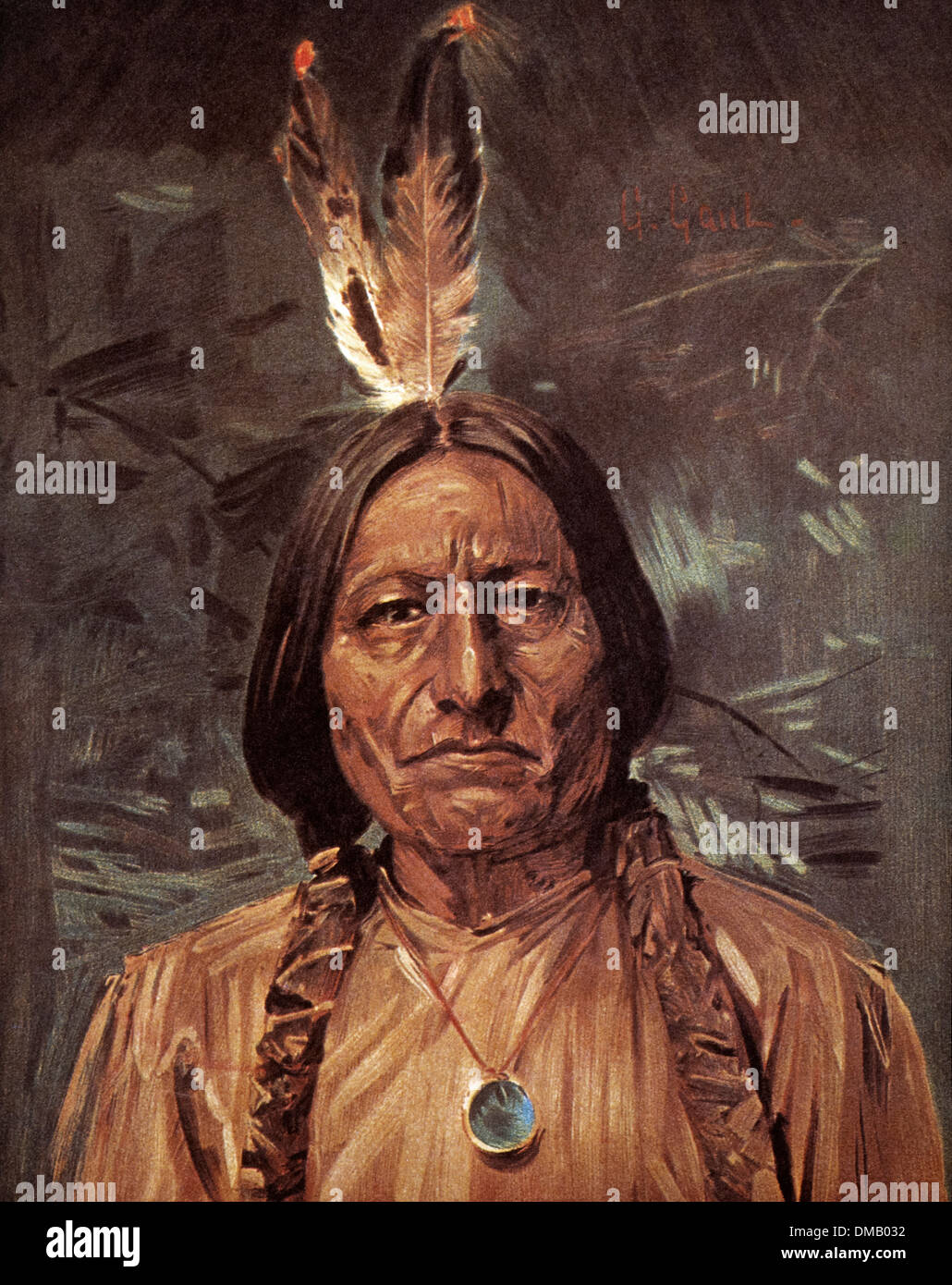

Tatanka Iyotake: The Unyielding Spirit of Sitting Bull, Lakota Holy Man and Warrior

In the vast tapestry of American history, few figures loom as large and as complex as Sitting Bull. Born Tatanka Iyotake (meaning "Buffalo Bull Who Sits Down"), this Hunkpapa Lakota holy man, warrior, and chief became the embodiment of Native American resistance against the relentless tide of westward expansion. More than just a military leader, Sitting Bull was a spiritual guide, a defiant statesman, and a poignant symbol of a way of life under siege. His name echoes through the annals of time, inextricably linked with the Battle of Little Bighorn, but his story is far richer and more profound than a single, legendary victory.

To understand Sitting Bull is to understand the soul of the Lakota people in their twilight years of freedom. He was born around 1831 in what is now South Dakota, near the Grand River. From an early age, it was clear he was no ordinary boy. His father, Returns-Again, a respected warrior, carefully nurtured his son’s development. At just 10 years old, young Tatanka Iyotake killed his first buffalo, a significant rite of passage. Four years later, he achieved his first coup – touching an enemy warrior in battle – earning him his father’s name, Sitting Bull, a testament to his bravery and steadfastness.

But Sitting Bull’s path was not solely that of a warrior. He was also a wichasha wakan, a holy man, possessing deep spiritual insight and a profound connection to the Lakota sacred traditions. He underwent vision quests, sought guidance from the spirits, and practiced the sacred rites of his people. His spiritual authority, combined with his demonstrated courage and wisdom, earned him immense respect and influence among the Lakota and allied tribes. He believed fiercely in the inherent right of his people to live freely on their ancestral lands, unmolested by the encroaching white settlers and the U.S. government.

The mid-19th century brought an escalating conflict between the Lakota and the United States. Treaties were signed and then almost immediately broken by the U.S. government, particularly after the discovery of gold in the Black Hills – the Paha Sapa – a sacred land to the Lakota. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had explicitly guaranteed the Lakota these lands, but the gold rush ignited an insatiable demand for their seizure. Sitting Bull, unlike many other chiefs, never signed a treaty with the U.S. government. He famously declared, "When I was a boy, the Sioux owned the world. The sun rose and set on their land; they sent 10,000 men to battle. Where are the warriors today? Who slew them? Where are our lands? Who owns them?" This sentiment encapsulated his unwavering refusal to cede land or sovereignty.

As tensions mounted, Sitting Bull became a central figure in the Lakota resistance. He advocated for a united front of Native American tribes against the U.S. Army, recognizing that only through collective strength could they hope to preserve their way of life. His camp became a magnet for those who refused to be confined to reservations – a haven for "non-treaty" Indians, including Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors.

The year 1876 marked the climax of this conflict, the Great Sioux War. The U.S. government, frustrated by the refusal of Sitting Bull and others to return to reservations, launched a massive military campaign. In June, Sitting Bull conducted a Sun Dance, a grueling spiritual ceremony, during which he received a powerful vision: "I saw soldiers coming down like grasshoppers, with their heads down." This vision was interpreted as a prophecy of a great victory over the U.S. forces.

Days later, on June 25, 1876, that prophecy materialized at the Battle of Little Bighorn. While often credited as the military leader, Sitting Bull’s role was primarily spiritual and strategic. He did not directly lead warriors in the field but provided the spiritual foundation and unified the diverse tribal forces. Under the tactical leadership of warriors like Crazy Horse and Gall, the combined Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho forces annihilated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry, resulting in Custer’s infamous "Last Stand." It was a stunning and humiliating defeat for the U.S. Army, and the greatest victory for Native Americans against the U.S. military. For Sitting Bull, it was the validation of his vision and a moment of profound, albeit temporary, triumph.

However, the victory at Little Bighorn only intensified the U.S. government’s resolve. The full might of the American military was unleashed upon the remaining free tribes. Rather than surrender, Sitting Bull led his people north across the "Medicine Line" into Canada, seeking refuge in the "Grandmother’s Country" (Queen Victoria’s domain). For four years, from 1877 to 1881, he lived in exile in Saskatchewan, enduring harsh winters and dwindling buffalo herds, but savoring freedom. He famously refused to shake hands with General Nelson Miles, who had pursued him, declaring, "I want to know what you have got to say to me. I do not wish to have any conversation with you. I am not a dog to be kicked about."

Life in Canada proved unsustainable. The buffalo, their primary food source, were disappearing, and the Canadian government offered no aid, urging them to return to the U.S. Faced with starvation, Sitting Bull finally led his remaining 186 followers back across the border and surrendered at Fort Buford, North Dakota, on July 19, 1881. Upon his surrender, he stated, "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender." He was then held as a prisoner of war at Fort Randall for nearly two years before being allowed to return to the Standing Rock Agency in 1883.

Even on the reservation, Sitting Bull remained a figure of immense influence and subtle defiance. He refused to adopt the ways of the white man, continuing to practice Lakota traditions and resisting attempts to dismantle his people’s culture. In 1885, in a bizarre turn of events, he briefly joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. For four months, he traveled across the U.S., performing for curious white audiences. While some viewed this as a surrender to spectacle, Sitting Bull used the opportunity to connect with people, often speaking to audiences (through an interpreter) about the injustices his people faced. He reportedly gave away much of his earnings to impoverished children and admired the kindness of the audiences, but ultimately found the confinement and exploitation intolerable. "I would rather stay here," he told a journalist, "where I can see my own country." He left the show, returning to his humble cabin on the Grand River.

Sitting Bull’s final years were shadowed by the growing despair of his people. The buffalo were gone, the land diminished, and their traditions suppressed. It was in this atmosphere of desperation that the Ghost Dance movement emerged, a spiritual revival promising a return to the old ways and the disappearance of the white man. Sitting Bull, while not a direct adherent of the Ghost Dance prophet Wovoka, allowed his followers to practice it, recognizing it as a source of hope for his people. U.S. authorities, however, viewed the Ghost Dance as a dangerous, rebellious movement, fearing that Sitting Bull’s influence would spark another uprising.

On December 15, 1890, fearing his involvement in the Ghost Dance, Indian Agency police, led by Lieutenant Henry Bull Head, were sent to arrest Sitting Bull at his cabin on the Standing Rock Agency. A scuffle broke out between Sitting Bull’s supporters and the police. In the ensuing chaos, Sitting Bull was shot and killed. He was approximately 59 years old. His death, a tragic culmination of years of conflict and misunderstanding, sent shockwaves through the Lakota community and contributed directly to the atmosphere of fear and tension that would erupt just two weeks later in the horrific Wounded Knee Massacre.

Sitting Bull’s legacy is one of unwavering principle and indomitable spirit. He was not just a warrior who fought battles; he was a leader who fought for the soul of his people, for their right to self-determination and cultural integrity. His words, such as "Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children," resonate as a testament to his vision for a peaceful future, even as he resisted oppression. He remains a powerful symbol of Native American strength, resilience, and the enduring struggle for justice and recognition. His life, marked by courage, prophecy, and profound tragedy, serves as a vital reminder of the complex and often painful chapters of American history, and of the enduring power of a leader who refused to be broken.