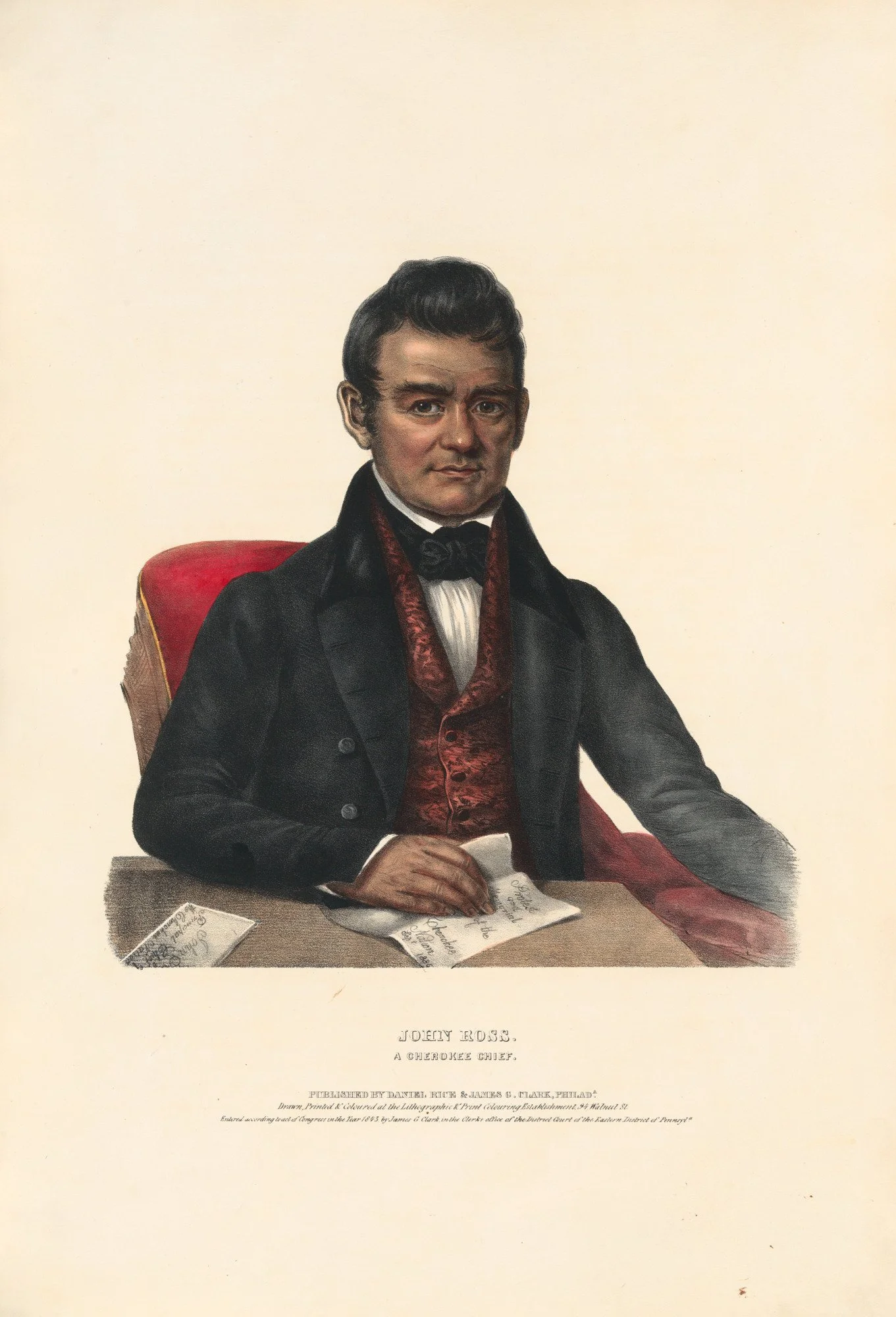

John Ross: The Unyielding Heart of a Nation Forged in Fire and Tears

His name echoes through the valleys of the Appalachian Mountains and across the plains of Oklahoma, a resonant symbol of defiance, resilience, and profound tragedy. John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation for nearly four decades, stood as a bulwark against the relentless tide of American expansion, battling presidents, states, and even members of his own tribe to preserve his people’s sovereignty and ancestral lands. His life, spanning from 1790 to 1866, encapsulates the epic struggle of Indigenous peoples in the face of manifest destiny, culminating in the forced removal known as the Trail of Tears – a defining, devastating chapter in American history.

Born in Turkeytown (present-day Rome, Georgia) in 1790, Ross was a child of two worlds. His father, Daniel Ross, was a Scottish immigrant and trader, and his mother, Molly McDonald, was a quarter-Cherokee woman whose lineage connected directly to prominent Cherokee families. This mixed heritage, far from being a disadvantage, positioned him uniquely within the evolving Cherokee society. Unlike many full-blood Cherokees who remained traditional, or white settlers who viewed Indigenous cultures as inferior, Ross straddled the divide. He was educated in English, spoke Cherokee fluently, and possessed a shrewd understanding of both the Cherokee legal traditions and the American political system.

From an early age, Ross demonstrated a keen intellect and a natural aptitude for leadership. He served as a clerk to the Cherokee agent, R.J. Meigs, and quickly rose through the ranks of the nascent Cherokee national government. By 1817, he was serving as the president of the National Committee, an early legislative body. It was during this period that the Cherokee Nation, under the influence of leaders like Ross, embarked on an extraordinary program of cultural and political modernization. They adopted a written constitution (1827) modeled on that of the United States, established a bicameral legislature, created a system of courts, and even developed a written language through Sequoyah’s syllabary (1821), leading to the launch of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper in 1828. These were not the "savages" often depicted in American propaganda; they were a self-governing, literate, and increasingly prosperous nation, capable of negotiating treaties and asserting their rights.

In 1828, John Ross was overwhelmingly elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, a position he would hold until his death. His ascension coincided with a period of escalating crisis. The discovery of gold on Cherokee lands in Georgia in 1829 unleashed a feverish land greed, intensifying calls for their removal. Georgia, in defiance of federal treaties, began to assert its jurisdiction over Cherokee territory, passing laws that nullified Cherokee laws, dispossessed them of their property, and even prohibited them from testifying in court against white men.

Ross understood that the Cherokee Nation’s survival hinged on its ability to assert its sovereignty and defend its treaty rights through legal and diplomatic means. He became the chief architect of the Cherokee strategy of resistance, which focused on a unified front, legal appeals, and direct engagement with the U.S. government. "We wish to remain on our lands," Ross declared, "and to maintain our rights, and to live in peace and harmony with our white neighbors."

The legal battle culminated in two landmark Supreme Court cases: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832). While the first case was dismissed on technical grounds, the second, Worcester v. Georgia, delivered a resounding victory for the Cherokee. Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for the majority, affirmed that the Cherokee Nation was "a distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force." It was a clear vindication of Cherokee sovereignty.

However, the triumph was hollow. President Andrew Jackson, a staunch advocate of Indian Removal and a man famously dismissive of judicial authority, reportedly scoffed, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" Jackson’s administration openly defied the Supreme Court’s ruling, emboldening Georgia and further isolating the Cherokee.

As pressure mounted, a deep schism emerged within the Cherokee Nation. A faction, despairing of Ross’s policy of resistance and convinced that removal was inevitable, began to advocate for negotiation. Led by prominent figures like Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot (the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix), this group came to be known as the "Treaty Party." They believed that clinging to their lands would only lead to their utter destruction, and that the only pragmatic choice was to secure the best possible terms for relocation.

John Ross vehemently opposed this view, arguing that the vast majority of the Cherokee people wished to remain and that no single faction had the authority to negotiate away the nation’s lands. He feared, correctly, that any such treaty would be seen as illegitimate by the majority of the Cherokee and would lead to chaos and disunity.

Despite Ross’s protests and the overwhelming opposition of the Cherokee National Council, the Treaty Party signed the Treaty of New Echota in December 1835. This treaty ceded all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for $5 million and land in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). It was signed by a minority faction without the consent of the vast majority of the Cherokee people or their Principal Chief. Ross immediately denounced it as a fraud, gathering thousands of signatures on petitions to Congress, asserting that the Treaty Party had no authority to represent the nation.

Congress, however, ratified the treaty by a single vote, largely due to Jackson’s influence and the prevailing political climate that prioritized westward expansion above all else. The stage was set for the tragic culmination of the removal policy.

In May 1838, under President Martin Van Buren, federal troops, led by General Winfield Scott, began the forced removal of the Cherokee people. Approximately 16,000 Cherokees were rounded up from their homes at bayonet point, often with little more than the clothes on their backs, and confined in internment camps. Ross, despite his profound anguish, remained with his people. He persuaded General Scott to allow the Cherokees to manage their own removal, hoping to minimize the suffering.

What followed was the "Trail of Tears." Beginning in the fall of 1838, the Cherokee, divided into thirteen detachments, were forced to march more than a thousand miles, often in brutal winter conditions, with inadequate food, clothing, and shelter. Diseases like dysentery, cholera, and whooping cough ravaged the columns. Along the way, Ross’s own wife, Quatie, died after giving her blanket to a child, a poignant testament to the human cost of the removal. By the time the last detachment arrived in Indian Territory in March 1839, an estimated 4,000 Cherokees – a quarter of the nation’s population – had perished.

The forced removal was a wound that would never fully heal, and its immediate aftermath in Indian Territory was marked by violence and further tragedy. The assassinations of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot in June 1839, carried out by full-blood Cherokees who viewed them as traitors for signing the fraudulent treaty, plunged the nation into a bitter civil conflict.

John Ross, now in the West, dedicated himself to reunifying his shattered people. He worked tirelessly to establish a new government in the Cherokee Nation (West), drafting a new constitution and seeking to heal the deep divisions. His leadership was crucial in rebuilding the nation, but challenges persisted, including the onset of the American Civil War. The Cherokee Nation, caught between Union and Confederacy, was once again torn apart, with Ross initially signing a treaty with the Confederacy under duress, only to later align with the Union.

John Ross died in Washington D.C. in 1866, still serving as Principal Chief, still fighting for his people’s rights in the aftermath of another devastating conflict. He had witnessed the rise and fall of a self-sufficient, modernizing nation, endured its near-annihilation, and painstakingly worked to rebuild it from the ashes.

John Ross remains a towering figure in American and Indigenous history. He was not without his critics, and the complexities of his decisions, particularly during the Civil War, are still debated. However, his unwavering commitment to Cherokee sovereignty, his strategic brilliance in navigating treacherous political waters, and his personal sacrifice in the face of overwhelming odds define his legacy. He embodies the tragic resilience of a people who, despite unimaginable loss, refused to be extinguished. His story is a powerful reminder of the enduring struggle for justice, self-determination, and the unyielding spirit of a nation forged in fire and tears.