Osceola: A Symbol of Defiance in the Face of American Expansion

The name Osceola echoes through the annals of American history, a resonant and often tragic symbol of indigenous resistance against the relentless tide of westward expansion. Not a principal chief by birthright, he nonetheless rose to become one of the most formidable and charismatic leaders of the Seminole people, defying the might of the United States in the brutal Second Seminole War. His story is one of unwavering courage, strategic brilliance, and ultimately, a betrayal that cemented his place as a martyr for his people.

To understand Osceola, one must first grasp the turbulent era in which he lived – a period defined by the Indian Removal Act, the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, and the violent clash between a rapidly expanding American republic and the sovereign nations it sought to displace. Osceola’s life, from his birth in a Creek village to his defiant stand in the Florida swamps, encapsulates this conflict, offering a poignant look at the human cost of empire.

The Formative Years: From Creek Lands to Florida Swamps

Osceola was born around 1804 in a Creek village near the Tallapoosa River in present-day Alabama. His mother was a Muscogee (Creek) woman named Polly Coppinger, and his father was likely an English trader, William Powell, though some accounts suggest a full Creek lineage. This mixed heritage, common among many Native Americans of the era, gave him a unique perspective, bridging the cultural divide even as he fought against its consequences.

His original name was Billy Powell, but he would come to be known as Osceola, or Asi-Yahola, a name derived from the ceremonial "black drink" – asi – and the cry, yahola, often uttered during its consumption. This name, "Black Drink Singer" or "Black Drink Crier," reflected his role in ceremonial life and hinted at his powerful voice and presence.

The early 19th century was a time of immense upheaval for the Creek Nation. The Creek War (1813-1814) and Andrew Jackson’s subsequent victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend resulted in the forced cession of vast Creek lands. In the aftermath, many displaced Creeks, including Osceola and his mother, migrated south into Spanish Florida, where they found refuge and intermingled with the existing indigenous populations – the remnant tribes of Florida, runaway slaves, and other Creek refugees – collectively forming the Seminole Nation.

It was in the wild, untamed landscapes of Florida that Osceola came of age. He witnessed firsthand the increasing encroachment of American settlers, the escalating tensions, and the broken promises that characterized U.S.-Native American relations. He learned the Seminole way of life, adapting to the subtropical environment and mastering the skills of hunting, warfare, and survival in the dense cypress swamps and sawgrass marshes. Though not born into the Seminole lineage, he was adopted into their community and quickly distinguished himself through his intelligence, charisma, and fierce independence.

The Seeds of War: Defiance at Payne’s Landing

By the 1830s, the pressure on the Seminoles to cede their lands and relocate west of the Mississippi River had reached a fever pitch. President Andrew Jackson, a staunch proponent of "Indian Removal," saw Florida as strategically vital for American expansion and security. The Seminoles, however, viewed Florida as their ancestral home, a sanctuary they had fought to protect and where many had found freedom from slavery.

The flashpoint came with the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832. This agreement, purportedly signed by a small faction of Seminole chiefs under duress and misrepresentation, stipulated that the Seminoles would relinquish all their lands in Florida and relocate to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) within three years. Crucially, the treaty also mandated that a delegation of Seminole chiefs inspect the new lands and, if satisfied, confirm the treaty. When the delegation returned, they claimed they had been coerced into signing a ratification that they did not agree with.

Osceola, though not a principal chief, emerged as a vocal and unyielding opponent of the treaty. He argued passionately that the chiefs who signed did not represent the will of the entire nation, and that the treaty was a fraudulent attempt to dispossess them. His fiery rhetoric and unwavering stance resonated deeply with many Seminoles, especially the younger warriors and the Black Seminoles (descendants of runaway slaves who had formed strong alliances with the Seminoles), who feared re-enslavement if they moved west.

According to popular legend, at a council meeting in 1835 where the Seminoles were pressured to sign a document agreeing to removal, Osceola dramatically plunged his knife through the treaty, exclaiming, "The only treaty I will ever make with the white man is this!" While the exact historical accuracy of this dramatic act is debated, its symbolic power is undeniable, encapsulating Osceola’s resolute defiance and his refusal to be intimidated. It became a powerful emblem of Seminole resistance.

The Second Seminole War: A Master of Guerrilla Warfare

The Seminoles’ refusal to vacate their lands ignited the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), one of the longest, costliest, and most brutal Indian wars in U.S. history. Osceola, though never officially a "chief" in the traditional sense, quickly became the de facto military leader and a rallying figure for the Seminole resistance. His influence stemmed from his intelligence, his charisma, his oratorical skills, and his proven ability as a warrior and strategist.

The war began with a series of devastating blows delivered by the Seminoles. On December 28, 1835, Osceola reportedly led a small party that ambushed and killed Wiley Thompson, the U.S. Indian Agent with whom he had a personal feud and who had briefly imprisoned Osceola earlier that year. On the very same day, Major Francis L. Dade’s column of over 100 U.S. soldiers was ambushed and virtually annihilated by a large Seminole force led by Micanopy and Jumper, in what became known as the Dade Massacre. These coordinated attacks signaled the Seminoles’ unwavering determination and caught the U.S. military by surprise.

Throughout the war, Osceola and other Seminole leaders masterfully employed guerrilla tactics, using their intimate knowledge of the Florida landscape to their advantage. They launched swift, devastating raids from the swamps, striking U.S. forts and settlements, and then disappearing into the impenetrable wilderness. They avoided large-scale engagements, preferring hit-and-run attacks that wore down the American forces, frustrated their commanders, and inflicted heavy casualties. Osceola’s leadership inspired his warriors and became a source of constant vexation for the U.S. Army.

The U.S. military, accustomed to conventional warfare, found itself utterly unprepared for this elusive and adaptable enemy. Generals came and went, each failing to decisively defeat the Seminoles. The war became a quagmire, draining the U.S. treasury and public patience. Osceola became a legendary figure, both feared and respected by his adversaries, a symbol of the "unconquered spirit" of the Seminoles.

Betrayal and Imprisonment: A Dark Chapter

As the war dragged on, the U.S. military, under the command of General Thomas Jesup, grew increasingly desperate. Frustrated by the Seminoles’ resilience, Jesup resorted to a controversial and ultimately dishonorable tactic. In October 1837, under the pretense of peace negotiations, Jesup invited Osceola and other Seminole leaders to a parley near Fort Peyton (near St. Augustine), promising them safe conduct under a white flag of truce.

However, once Osceola and his delegation arrived, they were immediately seized and imprisoned on Jesup’s direct orders. This blatant violation of the laws of war and diplomatic protocol was widely condemned, even by some American officials, as a stain on the nation’s honor. Jesup defended his actions by claiming that Osceola had previously violated truces, but the act remains a dark chapter in U.S. military history.

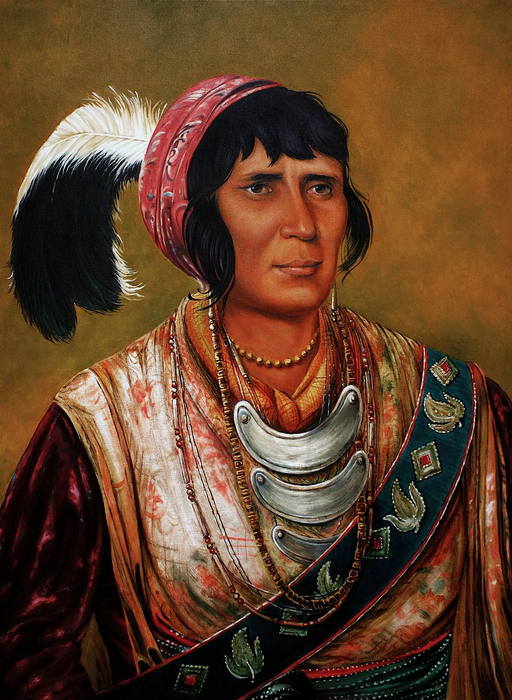

Osceola was initially held at Fort Marion (now the Castillo de San Marcos) in St. Augustine. His capture was a major blow to the Seminole resistance, though it did not end the war. While imprisoned, he became a celebrity of sorts, attracting visitors, including artists like George Catlin, who painted his famous portraits, capturing his dignified and defiant spirit.

Despite his fame, Osceola’s health deteriorated rapidly. He was already suffering from chronic malaria and a severe throat infection, possibly quinsy. Recognizing his declining condition, Jesup ordered his transfer to Fort Moultrie, near Charleston, South Carolina, hoping that a change of climate might improve his health and allow for further interrogation.

The Final Days and Enduring Legacy

Osceola arrived at Fort Moultrie in December 1837, a frail and ailing man. His condition continued to worsen, and on January 30, 1838, he died, likely from the throat infection and malaria. He was approximately 34 years old.

Even in death, Osceola’s story took a macabre turn. Dr. Frederick Weedon, the attending physician at Fort Moultrie and the post surgeon, performed an autopsy. In a shockingly disrespectful act, Weedon then decapitated Osceola, removing his head and preserving it, allegedly for medical study and as a personal trophy. The rest of Osceola’s body was buried with military honors near the sally port of Fort Moultrie.

Weedon later used the skull to frighten his children, and it eventually passed through several hands, including that of a New York physician and ultimately P.T. Barnum, before its fate became uncertain, with some believing it was lost in a fire. This ghoulish act underscored the dehumanization that Native Americans often faced, even after death.

Osceola’s death, though tragic, did not end the Seminole War. The conflict continued for another four years, fueled by the Seminoles’ outrage over his capture and death, and their unwavering determination to retain their homeland. His martyrdom only strengthened their resolve.

Today, Osceola remains a potent symbol of indigenous resistance, courage, and the devastating impact of colonial expansion. He is remembered not as a defeated warrior, but as an unconquered spirit who, against overwhelming odds, stood firm for his people’s rights and homeland. His story serves as a powerful reminder of the profound injustices committed during the era of Indian Removal and the enduring legacy of those who dared to defy it. His name echoes not just through history books, but in the hearts of those who continue to fight for justice, sovereignty, and the recognition of indigenous rights.