The Silent Strength: Unveiling the True Sacagawea

Her name echoes through American history, a symbol of resilience, guidance, and cross-cultural understanding. Sacagawea, the young Shoshone woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their epic journey to the Pacific, is an iconic figure, her image gracing coinage and monuments. Yet, despite her enduring fame, the true person behind the legend often remains shrouded in myth, her remarkable story frequently overshadowed by the very expedition she helped to shape. Who was Sacagawea, beyond the simplified narratives? She was a woman of extraordinary courage and adaptability, a vital, often underestimated, force in one of America’s most pivotal explorations, whose contributions were etched not into written logs by her own hand, but into the very fabric of the expedition’s success.

Born around 1788 into the Lemhi Shoshone tribe near the modern-day border of Idaho and Montana, Sacagawea’s early life was marked by the harsh realities of tribal conflict and displacement. At approximately 12 years old, while her people were camped along the Jefferson River, she was captured by a raiding party of Hidatsa warriors, enemies of the Shoshone. This traumatic event severed her ties to her homeland and family, thrusting her into an unfamiliar world hundreds of miles from her birth village. She was taken to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages near present-day Washburn, North Dakota, a bustling hub of trade and intertribal relations.

It was here, amidst a new culture and language, that Sacagawea’s life took another pivotal turn. Sometime around 1803 or 1804, she, along with another young Shoshone woman, was acquired by Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trapper and interpreter who had made his home among the Hidatsa. Charbonneau took Sacagawea as one of his wives, likely through a form of traditional custom or purchase. It was a union that, by all accounts, offered her little agency, but it would inadvertently place her on the cusp of an adventure that would secure her place in history.

The winter of 1804-1805 found Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, leaders of the Corps of Discovery, establishing Fort Mandan near the Hidatsa villages. Their mission, commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, was to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase, map the territory, establish trade relations with Native American tribes, and find a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean. As they prepared to push westward into uncharted territory, they recognized the desperate need for interpreters, particularly someone who could speak Shoshone. They knew the Shoshone controlled the horses vital for crossing the formidable Rocky Mountains.

It was Charbonneau who offered his services as an interpreter, boasting of his Shoshone wife. Though initially hesitant about bringing a woman, especially one who was heavily pregnant, Lewis and Clark quickly understood the strategic advantage Sacagawea offered. She was not just a speaker of Shoshone; she was a native Shoshone, possessing invaluable knowledge of the terrain, its edible plants, and the customs of her people. On February 11, 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to her son, Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, whom Clark affectionately nicknamed "Pomp" (meaning "first son" in Shoshone). Just weeks later, with a newborn infant strapped to her back, Sacagawea embarked on the journey of a lifetime.

Sacagawea’s contributions to the Corps of Discovery were multifaceted and indispensable, far exceeding the initial expectation of her role as merely a translator. Her presence itself was a powerful diplomatic asset. As Clark noted in his journal, "a woman with a party of men is a token of peace." Native American tribes encountered along the route, accustomed to seeing only male war parties, were reassured by the sight of Sacagawea and her infant. Her presence signaled that the expedition was not a war party but a peaceful endeavor, opening doors for negotiation and trade that might otherwise have remained closed.

Her linguistic skills proved vital at critical junctures. While Charbonneau served as an interpreter from Hidatsa to French, and Private François Labiche translated from French to English for Lewis and Clark, Sacagawea provided the crucial final link, translating from Shoshone to Hidatsa. This chain of interpretation, though cumbersome, was the only way to communicate with the Shoshone, without whom the expedition could not have acquired the horses necessary to cross the Continental Divide. When the Corps finally encountered a band of Shoshone in August 1805, it was Sacagawea who recognized their chief, Cameahwait, as her own brother. This poignant reunion, facilitated by her linguistic bridge, solidified the alliance, ensuring the expedition received the horses and guidance they desperately needed.

Beyond translation, Sacagawea was an invaluable guide and a living encyclopedia of the land. Having grown up in the region, she could identify edible plants and roots, augmenting the expedition’s often meager diet and helping them avoid poisonous ones. She knew where to find berries, camas roots, and wild licorice, providing crucial sustenance and even medicinal remedies. Her knowledge of the landscape, though not always explicitly cited as "guidance" in the journals, implicitly helped the Corps navigate difficult terrain, particularly as they approached the Shoshone lands she remembered from childhood.

One of the most dramatic illustrations of Sacagawea’s quick thinking and bravery occurred in May 1805, when a sudden squall capsized one of the expedition’s pirogues (a dugout canoe). Amidst the chaos, as precious instruments, medical supplies, and the expedition’s irreplaceable journals floated away, Sacagawea, despite holding her infant, calmly and expertly retrieved many of the floating items. Clark later wrote in his journal: "Sacagawea had the presence of mind to save most of the loose articles which were washed out of the boat." Her actions saved critical records and supplies, without which the expedition’s scientific and historical achievements would have been severely hampered, perhaps even lost entirely.

Throughout the arduous journey, Sacagawea endured immense physical hardship. She traversed thousands of miles on foot, over mountains and through dense forests, often battling illness and exhaustion, all while caring for an infant. Her resilience was extraordinary, a testament to her strength and determination. The journals occasionally mention her ailments, but always with the underlying tone of her continuing to push forward, a silent, unwavering force within the expedition.

Upon the Corps’ successful return to the Mandan villages in August 1806, Sacagawea’s journey with Lewis and Clark ended. She, Charbonneau, and Jean-Baptiste resumed their lives among the Hidatsa. Lewis and Clark, recognizing her immense contributions, offered Charbonneau payment and even extended an invitation for him to bring Sacagawea and Jean-Baptiste to St. Louis. Clark, in particular, had grown fond of "Pomp" and offered to raise and educate him, an offer Charbonneau eventually accepted.

What happened to Sacagawea after the expedition remains a subject of historical debate and uncertainty, a poignant reflection of how little agency and record-keeping were afforded to Native American women of her era. The most widely accepted account, supported by Clark’s records, indicates that Sacagawea died at Fort Manuel Lisa in present-day South Dakota on December 20, 1812, likely from a "putrid fever" (possibly typhus), at the young age of around 24. John Luttig, a clerk at the fort, recorded her death, noting she was Charbonneau’s "wife" and had a daughter named Lizette. Clark subsequently adopted Lizette and formalized his guardianship of Jean-Baptiste.

However, an alternative narrative, strongly held by some Shoshone oral traditions and supported by some historical interpretations, suggests that Sacagawea lived much longer, eventually leaving Charbonneau and returning to her Shoshone people in Wyoming. In this account, she lived to an old age, dying on the Wind River Reservation in 1884. Proponents of this theory point to discrepancies in names and dates in historical records and the strong oral tradition. While the 1812 death is generally accepted by mainstream historians due to contemporary written records, the enduring mystery only adds to the layers of her story, highlighting the challenges of reconstructing Native American histories from colonial records.

Regardless of the precise date of her death, Sacagawea’s legacy is undeniable and multifaceted. For much of the 19th century, her role was largely overlooked in historical accounts of the Lewis and Clark expedition, which focused primarily on the male explorers. It was not until the early 20th century, spurred by the women’s suffrage movement and a growing interest in American Western history, that her contributions began to be recognized and celebrated. She became a potent symbol of female strength, courage, and resourcefulness.

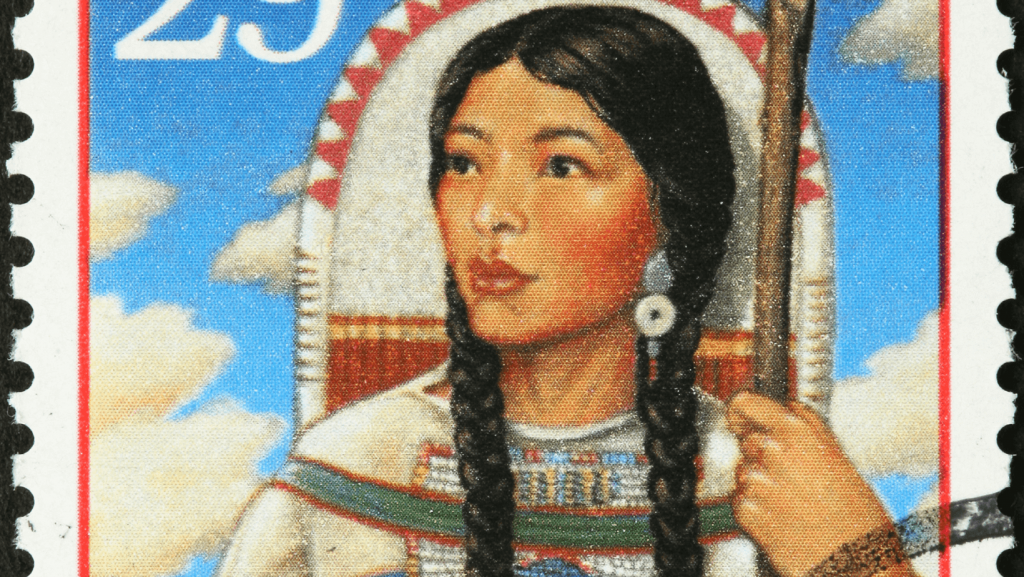

Today, Sacagawea is revered as a national heroine, an embodiment of the American spirit of exploration and resilience. She is seen as a bridge between cultures, a symbol of Native American contributions to the nation’s founding, and a testament to the vital, often unacknowledged, roles women have played in history. Her image on the U.S. dollar coin, carrying her son Jean-Baptiste, serves as a daily reminder of her unique place in the nation’s narrative.

Yet, it is crucial to remember that the Sacagawea we celebrate is, in part, a construct of historical interpretation and romanticization. Her own voice is largely absent from the historical record, filtered through the journals of Lewis and Clark, who, while generally respectful, viewed her through their own cultural lens. We know her through their observations of her actions, her quiet determination, and her indispensable knowledge.

In conclusion, Sacagawea was far more than a mere footnote in the annals of American exploration. She was a survivor, a linguist, a guide, a diplomat, and a mother, all while navigating a world that offered her little control over her own destiny. Her quiet strength and profound contributions ensured the success of an expedition that irrevocably shaped the course of American history. Sacagawea’s journey was not just westward to the Pacific, but a profound testament to the power of human spirit, a silent strength that continues to resonate across centuries, inviting us to look beyond the myth and truly appreciate the remarkable woman she was.