Who Was Sequoyah? The Genius Who Gave a Nation Its Voice

In the annals of human ingenuity, few stories resonate with the profound impact and sheer brilliance of Sequoyah, the Cherokee polymath who, against all odds, gifted his people the power of the written word. His achievement was not merely the creation of an alphabet, but the single-handed invention of a complete and highly efficient syllabary, transforming the Cherokee Nation almost overnight and ensuring the survival of their language and culture through generations of immense challenge.

Imagine a world where your spoken language, rich with history and nuance, has no written form. Imagine the frustration of observing other cultures communicate through "talking leaves" – written documents – while your own vibrant oral traditions are vulnerable to memory’s fallibility and the erosion of time. This was the world of the Cherokee in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it was this profound observation that ignited an intellectual fire in a man named Sequoyah.

Born around 1770 in Tuskegee, Tennessee, to a Cherokee mother, Wut-teh, and a father believed to be Nathaniel Gist, a Virginia fur trader, Sequoyah was known in his youth by his Cherokee name, Sikwoya, which some sources translate to "Pig’s Foot" – a curious and somewhat ironic moniker for a man of such intellectual stature. Unlike his father, who abandoned the family early on, Sequoyah remained deeply rooted in Cherokee culture. He was a silversmith by trade, a skilled artisan who understood the precision of crafting intricate objects. But it was his mind, not his hands, that would forge his most enduring legacy.

Sequoyah grew up in a period of intense cultural exchange and conflict. The Cherokee Nation, one of the most sophisticated and populous Native American tribes, was increasingly interacting with European Americans. Treaties were signed, laws were enacted, and Christian missionaries arrived, often with written Bibles in hand. Sequoyah observed how the "white man" used written characters to record transactions, communicate across vast distances, and preserve laws and histories. This stark contrast between the ephemeral nature of spoken language and the permanence of written text became an obsession.

"He realized that a written language would give his people the same advantages as the whites," historian Robert G. Miller noted. "It would allow them to record their laws, preserve their history, and communicate more effectively."

Initially, Sequoyah’s peers scoffed at his endeavors. He was illiterate himself, speaking only Cherokee, and his early attempts were crude and misguided. For years, he experimented with pictographs, symbols representing entire words or concepts, much like ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. This approach proved unwieldy and impractical, requiring thousands of characters to represent the vastness of the Cherokee language. His family, particularly his wife and young daughter, Ayoka, often bore the brunt of his singular focus, as his work on the "talking leaves" consumed his time and resources, leading to accusations of idleness or even witchcraft.

The breakthrough came around 1809, after a decade of relentless effort. Sequoyah, perhaps inspired by his observation of English alphabet letters, had a revelation: language could be broken down not into individual words or concepts, but into syllables. He realized that the Cherokee language, despite its complexity, was composed of a relatively small number of distinct phonetic syllables. This was his "Eureka!" moment.

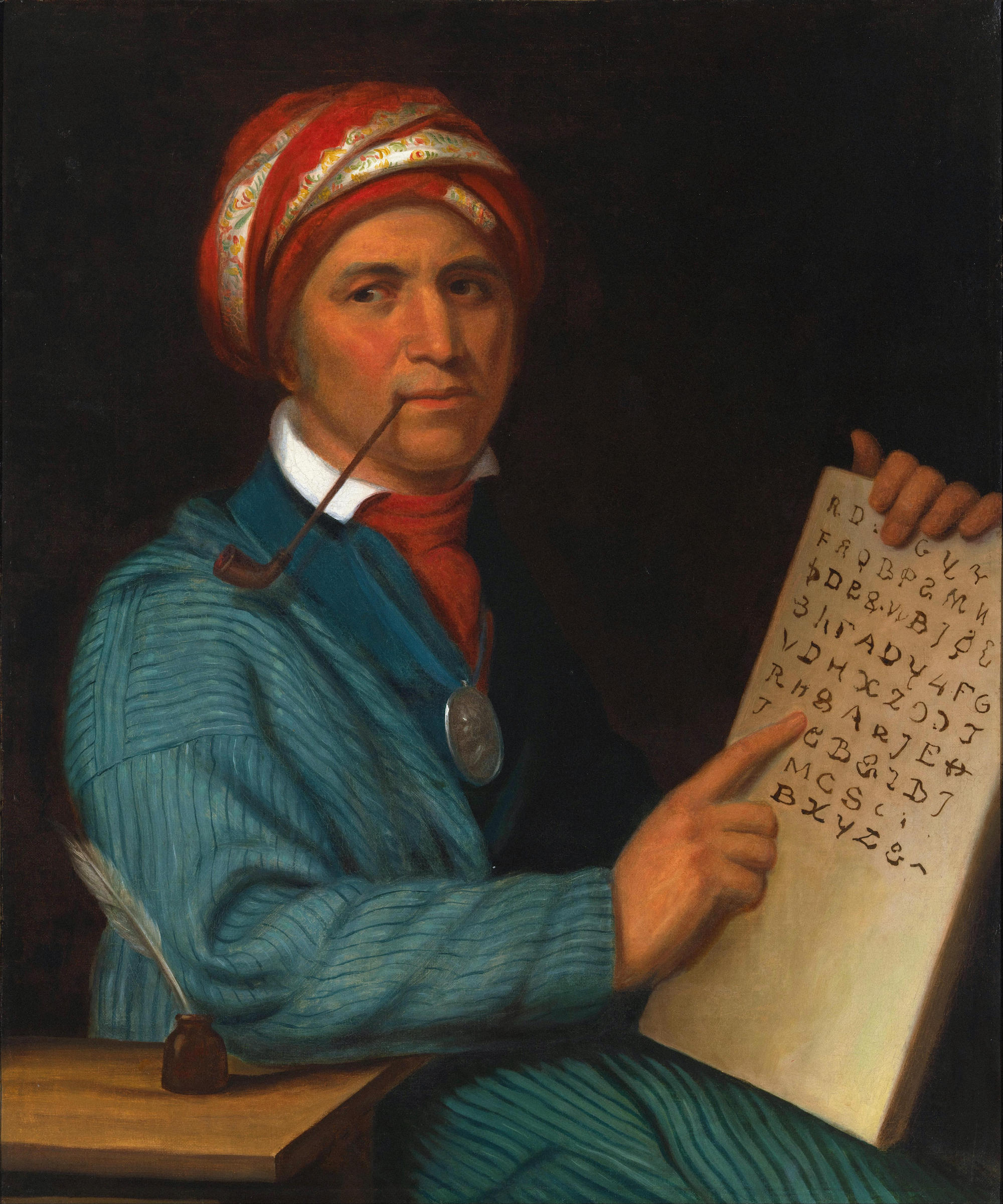

With this insight, he abandoned pictographs and began to develop a system where each symbol represented a syllable, not a whole word or a single sound (like a consonant or vowel). He meticulously identified 86 distinct syllables in the Cherokee language. For each syllable, he designed a unique character. Some of his characters were adapted from English letters he saw in books, though he had no knowledge of their original sounds. For example, the English letter "D" became the Cherokee symbol for "a," and "R" became "e." Others he invented entirely. The result was a remarkably elegant and efficient syllabary.

The testing phase was crucial and dramatic. Skepticism among the Cherokee leaders was high. To prove his system worked, Sequoyah enlisted his young daughter, Ayoka, who had learned the characters alongside him. He would send her out of earshot, and then ask a Cherokee elder to dictate a message to him. He would write it down, and then Ayoka would return and read it aloud perfectly. The elders were astonished. Some initially suspected magic, but repeated demonstrations dispelled their doubts.

In 1821, after twelve years of dedicated work, the Cherokee Nation officially adopted Sequoyah’s syllabary. The impact was immediate and revolutionary. Unlike complex alphabets that require years to master, the Cherokee syllabary was incredibly easy to learn. An adult could become literate in a matter of days or weeks. Within months, thousands of Cherokees learned to read and write. The literacy rate among the Cherokee quickly surpassed that of their white neighbors, reaching an astonishing 90% within a few years.

This rapid embrace of literacy transformed the Cherokee Nation. Laws and treaties could be accurately recorded and disseminated. Religious texts were translated. Most famously, in 1828, the Cherokee Nation began publishing its own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix (or Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi), printed in both English and Cherokee, using Sequoyah’s syllabary. This newspaper became a vital tool for communicating information, fostering national identity, and advocating for Cherokee rights against increasing U.S. government pressure.

The syllabary became a lifeline during one of the darkest periods in Cherokee history: the forced removal known as the Trail of Tears. As thousands of Cherokees were brutally marched westward from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in the late 1830s, the ability to read and write helped them organize, communicate, and maintain their cultural cohesion in the face of immense suffering and dislocation. Letters written in the syllabary passed between scattered families, providing comfort and continuity.

Sequoyah himself continued to serve his people. After the removal, he traveled extensively, seeking to unite fragmented Cherokee bands and advocating for the creation of a universal writing system for other Native American tribes. In 1842, he embarked on a journey to the American Southwest, hoping to find a lost band of Cherokees who had migrated there years earlier and perhaps introduce them to his syllabary. He died in August 1843 in San Fernando de Taos, New Mexico, during this expedition, far from his original homeland. His burial place remains unknown.

Sequoyah’s legacy, however, is anything but lost. He is perhaps the only person in recorded history to have single-handedly created a fully functional writing system from scratch, without the benefit of knowing any other writing system beforehand. His genius was not in adapting an existing script, but in conceiving an entirely new conceptual framework for written language.

His contributions were recognized, not only by his own people, but by the wider world. The magnificent giant redwood trees of California, Sequoiadendron giganteum and Sequoia sempervirens, were named in his honor by Austrian botanist Stephen Endlicher in 1847. This enduring tribute in nature speaks to the monumental scale of his achievement – a silent, towering testament to a man who truly stood tall in human history.

Sequoyah’s story transcends that of a mere inventor; it is the saga of a visionary who understood the profound power of communication. He did not seek personal glory or wealth. His motivation was rooted in a deep love for his people and an unwavering belief in their capacity for progress and self-determination. He gave the Cherokee Nation not just a tool, but a means of empowerment, a way to preserve their heritage, and a voice that continues to resonate today. The Cherokee language, written in the elegant strokes of his syllabary, remains a living testament to Sequoyah, the illiterate genius who taught a nation to read and write, forever changing their destiny.