William Anderson: Lens on the Last Frontier

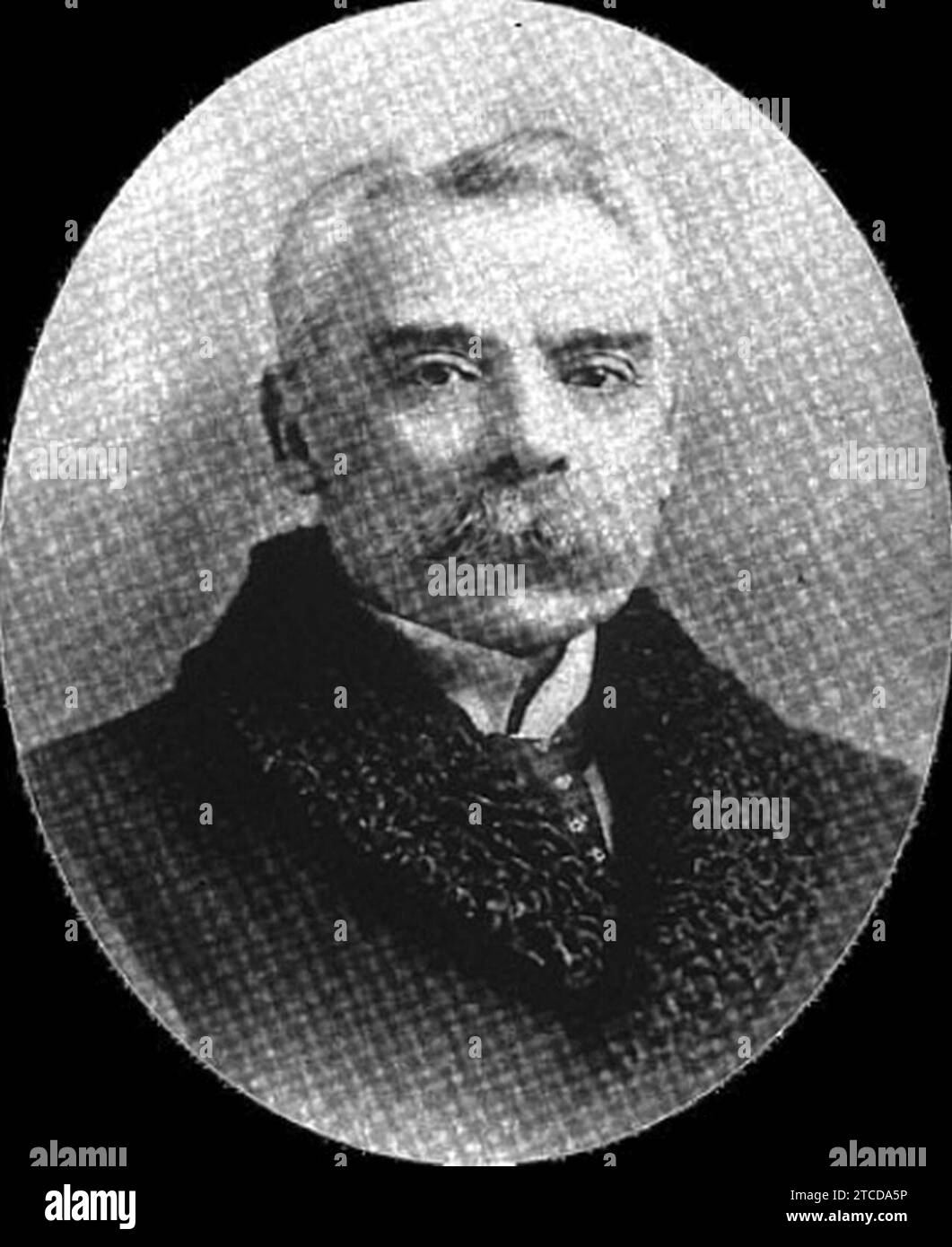

In the annals of photography, certain names shine like beacons, illuminating epochs and capturing the spirit of their age. Among them, William Anderson, a lesser-known but profoundly influential figure, stands as the unblinking eye of a vanishing American frontier. Born in Canada in 1860, Anderson’s lens didn’t just record landscapes; it chronicled the raw ambition of the Gold Rush, the rugged beauty of the Alaskan wilderness, and the faces of those who dared to chase fortune in the farthest reaches of the continent. His work, steeped in the journalistic ethos of documentation and the artistic pursuit of composition, offers an unparalleled visual history of a pivotal moment in North American expansion.

Anderson’s journey into the world of photography began not in the frozen North, but under the Californian sun. Like many aspiring artists and entrepreneurs of his generation, he was drawn to the burgeoning opportunities of the American West. By the late 1880s, he had established himself in California, working as a photographer and honing his craft. This period was critical, allowing him to master the demanding techniques of large-format photography, including the handling of bulky cameras, heavy glass plate negatives, and volatile chemical processes, all of which required meticulous attention to detail and a keen understanding of light and shadow. His early work likely focused on the scenic grandeur of California’s landscapes – the towering redwoods, the dramatic coastlines, and perhaps the nascent urban centers – providing him with a strong foundation for the far more challenging environments he would soon encounter.

The turn of the 20th century, however, brought a seismic shift in Anderson’s career trajectory. The discovery of gold in the Klondike region of Canada in 1896, followed by subsequent strikes in Nome, Alaska, ignited one of history’s most frantic and arduous gold rushes. Thousands flocked north, driven by dreams of instant wealth, enduring unimaginable hardships along the way. For Anderson, this wasn’t just a news story; it was a calling. Recognizing the unprecedented historical significance of the event, he packed his cumbersome equipment and headed north, exchanging the gentle light of California for the stark, unforgiving glare of the Arctic sun.

The challenges of photography in the Klondike and Alaskan territories were immense. Temperatures plummeted far below freezing, making the handling of chemicals and plates a perilous endeavor. The sheer logistics of transporting heavy wooden cameras, tripods, glass negatives, and portable darkroom tents over icy mountain passes, through dense forests, and across treacherous rivers were a testament to Anderson’s extraordinary dedication. Each photograph taken was not merely a click of a shutter but a triumph of human ingenuity and endurance against nature’s formidable will.

Anderson quickly became one of the most prolific and respected photographers of the Klondike Gold Rush. His most significant partnership began around 1900 with P.P. Larss, a Swedish immigrant who had also made his way north. Together, Larss & Anderson established studios in Nome and Dawson City, becoming the premier photographic chroniclers of the region. Their operation was both an artistic endeavor and a shrewd business enterprise. They didn’t just take pictures; they mass-produced them. "The demand for images from the Klondike was insatiable," notes historian Kathryn Morse. "Miners wanted proof of their adventures, families back home yearned for glimpses of their loved ones, and the wider world was captivated by the epic struggle unfolding in the North."

Larss & Anderson produced an astonishing volume of work, ranging from individual portraits of hopeful prospectors, often adorned with their tools and weary expressions, to panoramic views of boomtowns teeming with makeshift saloons, banks, and general stores. They captured the iconic scenes of the era: long lines of "stampeders" ascending the Chilkoot Pass, their backs laden with supplies; dogsled teams navigating snowy trails; bustling steamboats plying the Yukon River; and the chaotic, muddy streets of Dawson City and Nome, where fortunes were made and lost overnight. Their images are not just static records; they pulsate with the energy, desperation, and rugged optimism of the time.

Beyond the dramatic landscapes and the bustling human activity, Anderson’s lens also focused on the Indigenous peoples of the North – the Tlingit, Inuit, and Athabascan communities whose lives were irrevocably altered by the influx of outsiders. While today we view such portrayals through a more critical lens, acknowledging the historical power imbalances and potential for exoticism, Anderson’s photographs offer invaluable ethnographic records. They capture traditional dress, hunting practices, village life, and the stoic dignity of people facing profound cultural change. These images, though sometimes framed by the prevailing biases of the era, nonetheless provide a crucial visual archive of cultures in transition, offering insights that written accounts often miss.

What sets Anderson’s work apart is his remarkable ability to blend documentary precision with artistic sensibility. He possessed a keen eye for composition, often framing his subjects against the vast, dramatic backdrops of the Alaskan wilderness. His landscapes convey both the immense scale of nature and the tiny, often fragile presence of humanity within it. His portraits, while frequently taken in studio settings, often capture a sense of individuality and resilience in the faces of those who braved the harsh frontier. He understood the power of light, using it to sculpt the contours of a glacier or to highlight the determined gaze of a gold miner.

The commercial success of Larss & Anderson was due in no small part to their innovative distribution methods. They produced postcards, stereographs (images that create a 3D effect when viewed through a special device), and photographic prints that were widely sold and collected. These mass-produced images played a crucial role in shaping public perception of the Gold Rush and the Alaskan frontier, disseminating visual information far and wide and creating a lasting iconography of the era. Anderson, through his partnership, became a crucial visual storyteller, sharing the epic saga of the North with a global audience.

As the Gold Rush waned and the initial frenzy subsided, so too did the intensity of Anderson’s work in the North. By the early 1910s, he had likely moved on, perhaps returning to California or pursuing other photographic ventures. The precise details of his later life are somewhat elusive, a common fate for many pioneering photographers who were more focused on their craft than on self-promotion or meticulous record-keeping. However, his legacy was already cemented.

William Anderson’s photographs are more than just historical artifacts; they are windows into a world that exists now only in the silver halide crystals he so painstakingly developed. They bear witness to a moment when the wild edges of a continent were being tamed, when fortunes were gambled on a whim, and when the human spirit was tested against the formidable might of nature. He captured the beauty and the brutality, the hope and the despair, the grandeur and the grit.

Today, Anderson’s work is preserved in major archives and museums, including the University of Washington Libraries, the Alaska State Library, and the National Archives of Canada, among others. Researchers, historians, and art enthusiasts continue to study his images, gleaning new insights into the social, economic, and environmental history of the American and Canadian North. His photographs remind us of the power of the camera not just to record, but to interpret, to evoke, and to connect us across time with the lives and landscapes of those who came before.

In an era before instantaneous digital capture, when each exposure was a significant investment of time, effort, and resources, William Anderson stood as a dedicated artisan and an intrepid journalist. He didn’t just point his camera; he immersed himself in the stories he sought to tell. His enduring legacy is a vibrant, compelling visual narrative of the Klondike Gold Rush and the Alaskan frontier, proving that a single lens, wielded with skill and courage, can illuminate an entire chapter of human history. He was, truly, the unblinking eye of the last great American frontier.